On 7 October, the European Central Bank (ECB) published its liquidity stress test results for 103 euro area banks. ECB’s increased focus on stressed liquidity is credit positive for these banks. As the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) has a very short 30-day horizon, ECB looking at liquidity stresses lasting six months provides a much more meaningful measure. The test results will be used to strengthen the liquidity risk assessment in the 2019 Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), but will not have a direct effect on capital requirements. Via Moody’s.

Overall, the stress test highlights a marked variation in euro area banks’ ability to cope with severe liquidity shocks. It demonstrated that there are pronounced pockets of vulnerability, with 75% of banks being unable to cope with a severe stress that lasted six months. While individual bank results were not released, the ECB stated that large universal banks and G-SIBs were the most exposed.

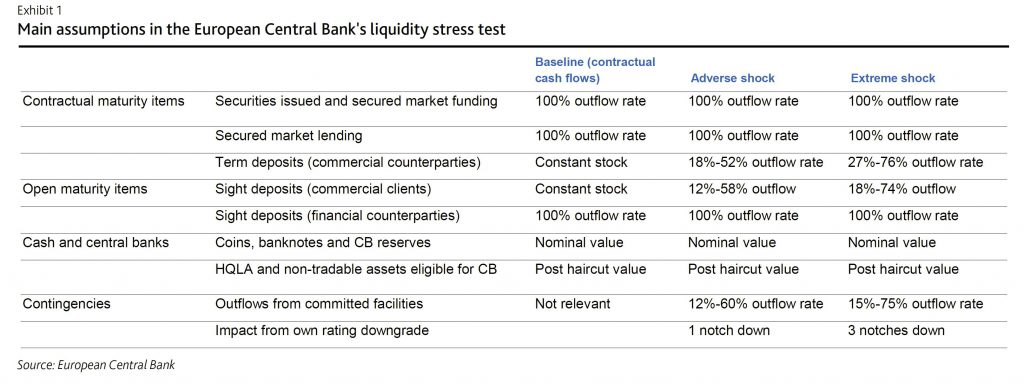

The ECB focused on idiosyncratic (rather than systemwide) shocks calibrated on the basis of recent liquidity crises. The effect was measured in terms of survival horizons by looking at banks’ cumulative cash flows and available counterbalancing capacity (i.e. the liquidity the banks can generate based on available collateral) in three scenarios. The scenarios include a baseline, in which the bank is no longer able to tap the wholesale funding market; an adverse shock, which adds a limited deposit outflow, limited withdrawals of committed lines, and a one-notch rating downgrade; and an extreme shock scenario, which adds severe deposit run-offs, pronounced withdrawals of committed lines, and a three-notch rating downgrade.

Overall, the banks’ reported median survival period was 176 days, or almost six months, under the adverse shock scenario and 122 days (just over four months) in the extreme shock scenario. Only 25% of the banks have liquidity buffers that would withstand the extreme shock scenario for six months or longer, and the majority (75%) have a survival period that is shorter than six months. Survival periods varied markedly, with differences driven mainly by the banks’ funding mix.

There are significant pockets of vulnerability. Although results for individual banks have not been disclosed, four banks from different

jurisdictions and with different business models have a survival period of less than six months even in the baseline scenario, which we consider very weak, and 11 banks have a survival period of less than two months under the extreme shock scenario. Universal banks and global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) are also harder hit by the stress scenarios.

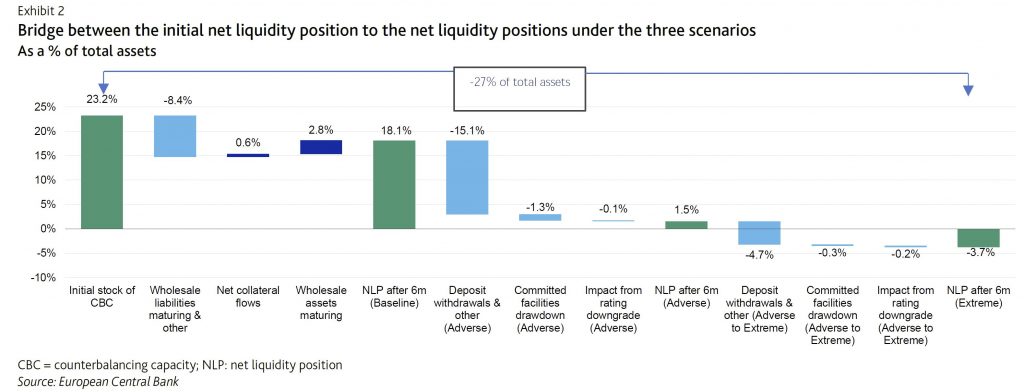

Exhibit 2 shows the (simple average) effect of the three scenarios compared to the initial stock of net liquidity, with overall outflows equivalent to around 27% of total assets under the extreme scenario. The key effect under the baseline scenario is caused by the lack of access to wholesale markets, followed by deposit withdrawals under the adverse and extreme scenarios.

Although any stress test must be based on assumptions and scenarios, we note that past liquidity crises (according to the ECB’s stress test announcement in February 2019) lasted between four and five months on average. However, 43% of the real life stresses lasted longer than six months. With a median survival horizon of a little longer than four months, many banks may have a survival horizon that may prove short, particularly in a bank-specific crisis with more limited opportunities for the central bank to intervene with extraordinary measures. It also points to the need for banks to mobilize additional non-tradable collateral in addition to the readily available liquidity buffers, which is one of the areas where the ECB observed scope for improvement.

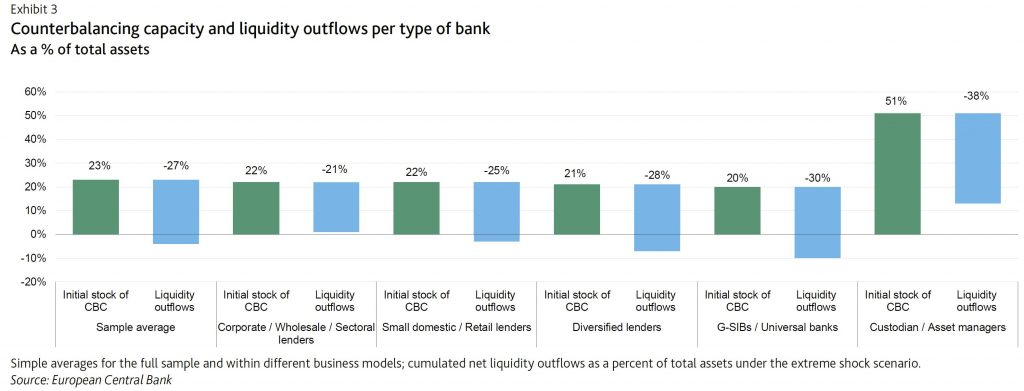

Universal banks and G-SIBs, which are generally more reliant on less stable deposits and wholesale funding, despite having large liquidity buffers, were the hardest hit by the stress scenarios. Their median survival in the adverse shock scenario was 126 days, and 80 days in the extreme shock scenario.

Small domestic and retail lenders, which generally benefit from more stable deposits and lower reliance on wholesale funding, were relatively less affected. Their median survival was more than 180 days under the adverse shock scenario and was 140 days under the extreme shock scenario, indicating that they would maintain positive liquidity for significantly

longer than the universal banks and G-SIBs. The results are in line with our assessment where large banks often have weaker funding and liquidity assessments compared to smaller domestic retail banks. Exhibit 3 shows the counterbalancing capacity and the liquidity outflows per type of bank, with G-SIBs/universal banks significantly more negatively affected compared to small domestic/retail lenders.

The stress test also identified vulnerabilities related to cash flows in foreign currencies, where survival periods generally are shorter than those reported at consolidated level. Whereas the median survival period in EUR was 125 days, the median survival periods in USD and GBP were 57 and 53 days, respectively. This suggests that the lessons during the global financial crisis have not been fully learnt. In addition, some banks’ collateral management practices, which are essential in the event of a liquidity crisis, also need improvement.

The ECB also cautioned that banks may underestimate the negative effect that a credit rating downgrade could trigger. Previous liquidity crises have shown that deteriorations can go quickly and fast.