The World Economic Forum has just released their 2020 report, the 15th in the series and they highlight ” long-mounting, interconnected risks” driven by their annual Global Risks Perception Survey which was completed by approximately 800 members of the Forum’s diverse communities.

They conclude that the world “cannot wait for the fog of geopolitical and geo-economic uncertainty to lift. Opting to ride out the current period in the hope that the global system will “snap back” runs the risk of missing crucial windows to address pressing challenges”.

At the time of writing, the IMF expected growth to be 3.0% in 2019—the lowest rate since the economic crisis of 2008-2009.

They say that today’s emerging economies are expected to comprise six of the world’s seven largest economies by 2050. Rising powers are already investing more in projecting influence around the world. And digital technologies are redefining what it means to exert global power. As these trends are unfolding, a shift in mindset is also taking place among some stakeholders—from multilateral to unilateral and from cooperative to competitive. The resulting geopolitical turbulence is one of unpredictability about who is leading, who are allies, and who will end up the winners and losers.

The global economy is faced with a “synchronized slowdown”, the past five years have been the warmest on record, and cyberattacks are expected to increase this year—all while citizens protest the political and economic conditions in their countries and voice concerns about systems that exacerbate inequality.

Indeed, the growing palpability of shared economic, environmental and societal risks signals that the horizon has shortened for preventing—or even mitigating—some of the direst consequences of global risks. It is sobering that in the face of this development, when the challenges before us demand immediate collective action, fractures within the global community appear to only be widening.

Global commerce has historically been a pillar and engine of growth—and a key tool for lifting economies out of downturns—but as we warn, significant restrictions were placed on global trade last year. This comes as G20 economies hold record high levels of debt and exhibit relatively low levels of growth. Ammunition to fight a potential recession is lacking, and there is a possibility of an extended low-growth period, akin to the 1970s, if lack of coordinated action continues. In addition, a potential decoupling of the world’s largest economies, the United States and China, is cause for further concern. The question for stakeholders—one that cannot be answered in the affirmative—is whether in the face of a prolonged global slowdown we are positioned in a way that will foster resiliency and prosperity.

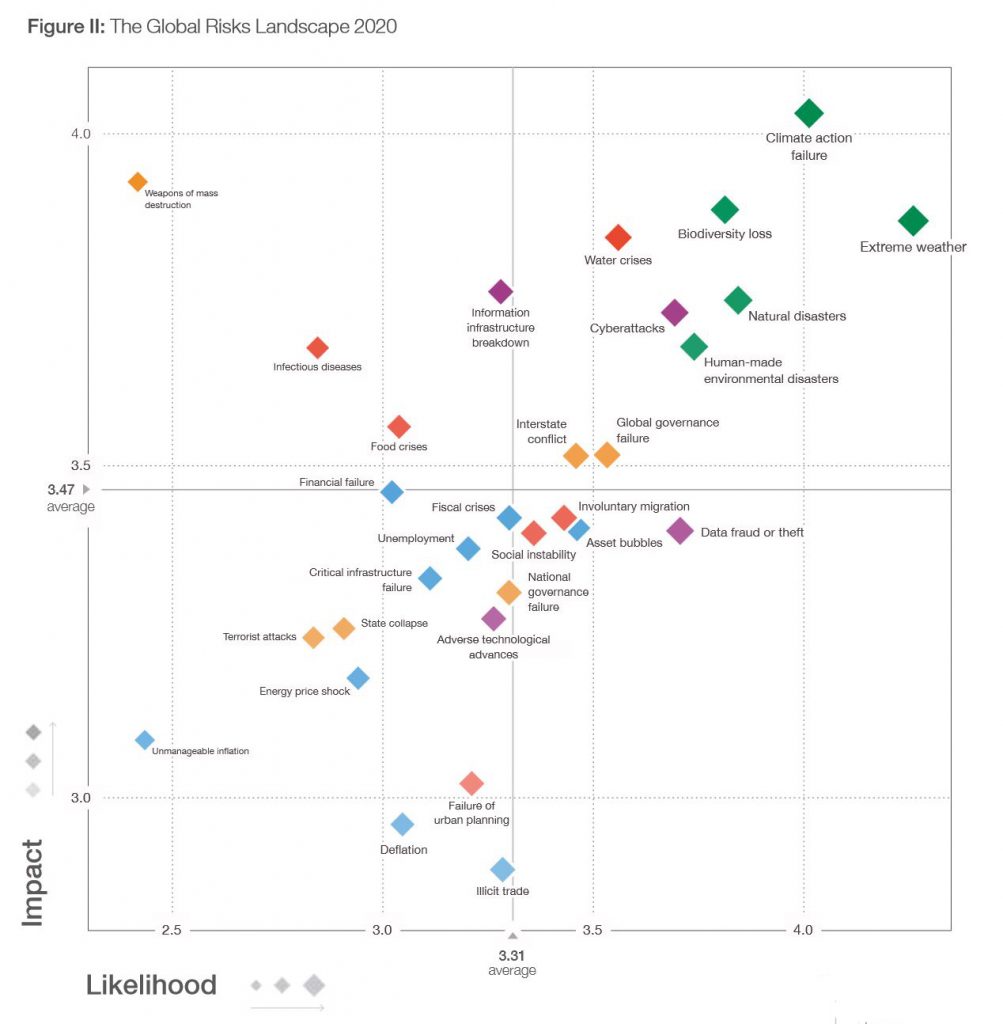

On the environment, we note with grave concern the consequences of continued environmental degradation, including the record pace of species decline. Respondents to our Global Risks Perception Survey are also sounding the alarm, ranking climate change and related environmental issues as the top five risks in terms of likelihood—the first time in the survey’s history that one category has occupied all five of the top spots. But despite the need to be more ambitious when it comes to climate action, the UN has warned that countries have veered off course when it comes to meeting their commitments under the Paris Agreement on climate change.

And on global health and technology, we caution that international systems have not kept up to date with the challenges of these domains. The global community is ill-positioned to address vulnerabilities that have come alongside the advancements of the 20th century, whether they be the widening application of artificial intelligence or the widespread use of antibiotics.

Today’s risk landscape is being shaped in significant measure by an unsettled geopolitical environment—one in which new centres of power and influence are forming—as old alliance structures and global institutions are being tested. While these changes can create openings for new partnership structures, in the immediate term, they are putting stress on systems of coordination and challenging norms around shared responsibility. Unless stakeholders adapt multilateral mechanisms for this turbulent period, the risks that were once on the horizon will continue to arrive.

The good news is that the window for action is still open, if not for much longer. And, despite global divisions, we continue to see members of the business community signal their commitment to looking beyond their balance sheets and towards the urgent priorities ahead.

They highlight the economic risks posed by global runaway climate change. Climate change is striking harder and more rapidly than many expected, with the bushfires that have ravaged Australia – as well as floods and droughts around the world – bringing the issue to the forefront of the global agenda.

They say, “alarmingly, global temperatures are on track to increase by at least 3°C towards the end of the century—twice what climate experts have warned is the limit to avoid the most severe economic, social and environmental consequences”.

The economic threat posed by climate change could impact everything from national economies to the mortgage and insurance industries. Worldwide economic damage from natural disasters in 2018 totalled US$165 billion, with that number set to increase if emissions remain at their current level.

In the United States alone, climate-related economic damage could reach 10 per cent of GDP by the end of the century, while over 200 of the world’s largest firms estimate that climate change will cost them a combined total of nearly US$1 trillion.

But the report says many businesses are still not planning on the physical and financial risks that climate change could have on their activities and value chains.

The WEF warns that avoiding the most severe economic and social consequences of global climate change means limiting global warming to just 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels. This equates to a remaining carbon budget of less than 10 more years of emissions at their current level – and demand for energy is only continuing to increase.