For the last four years or so average wages in Australia have barely kept pace with inflation, meaning no real pay rises. And all the while, the government has been betting on the market to improve things.

Treasurer Scott Morrison stated:

As the labour market tightens, that’s obviously going to lead over time to a boost in wages.

As the Treasurer asserted, economic theory says these conditions should lead to rising wages, but they aren’t. The country continues its record run of 26 years of economic growth and the banks and other big corporations continue to post record profits.

The Reserve Bank of Australia is at a bit of a loss, speculating at its latest meeting that maybe globalisation and technology are to blame.

However, to understand what’s really going on it’s helpful to look at something most economists and politicians ignore: history.

How past governments have dealt with low wages

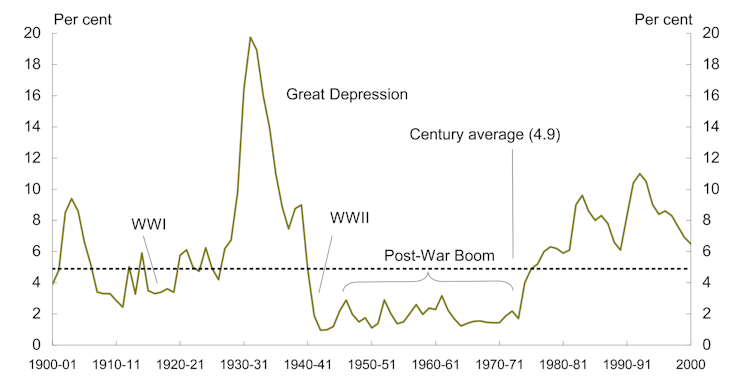

There was a period in Australia, and much of the rest of the developed world, from the end of the second world war to the early 1970s, that is often referred to as the “post-war boom”. During this roughly 25-year period, unemployment averaged 2%, inequality fell steadily and economic growth was strong.

Australia’s unemployment rate, 1901 – 2001

This didn’t happen by accident. Towards the end of the war, policymakers and economists began planning for the post-war period.

They had lived through the Great Depression with unemployment averaging 20% and then they had lived through the war, where the war effort resulted in full employment. They asked the obvious question: “If we can achieve full employment through government spending during the war, then why not during peace time?”

That question and the resulting policy answer, outlined in the Curtin government’s 1945 white paper Full Employment in Australia, resulted in the post-war boom with full employment and falling inequality for the next 25 years.

The 1945 white paper (a remarkable political document by today’s standards) tackled the complex questions of inflation, unemployment, wages and economic growth with mature nuance. Policy proposals weren’t made to appear win-win but weighed up costs and benefits, accepting that we must take responsibility for the costs.

One of the costs of a capitalist, market based system is unemployment. In this context, unemployment was not seen as an individual failing but as a collective responsibility. The paper stated the government should accept responsibility for stimulating spending on goods and services to the extent necessary to sustain full employment.

How far we have come from 1945. Today we blame and demonise the unemployed for not being in work, even though there are many more unemployed people than there are available jobs.

Rather than governments taking responsibility for full employment, they set up punitive “employment services” regimes that require the unemployed to jump through meaningless and often demoralising bureaucratic hoops or face financial penalties.

So, what happened in the 1970s to change our attitude to full employment so radically?

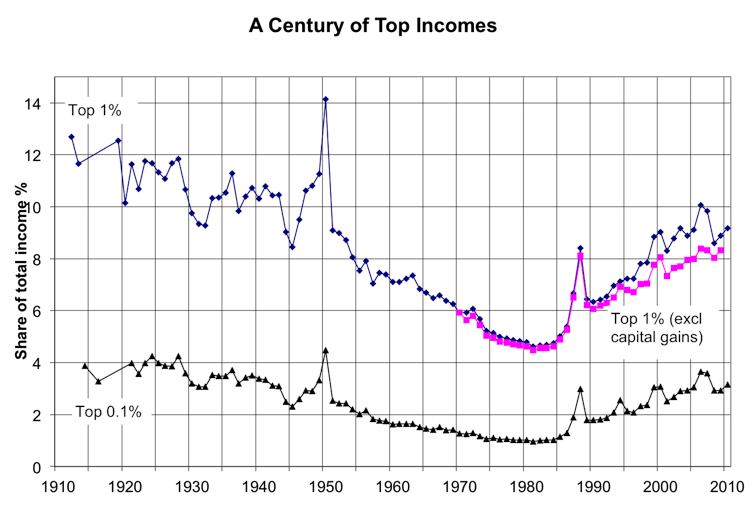

During the post-war boom, inequality had been steadily falling. That is, for 25 years, the proportion of the country’s output that was going to the rich was steadily falling. Unsurprisingly, the rich fought back.

Skyrocketing inflation combined with high unemployment (stagflation), caused by the oil shocks of the 1970s, allowed business representatives to claim that the Keynesian system that had given us the post-war boom was a failure.

Enter the age of individualism. Neoclassical economics and its political counterpart neoliberalism were all about individual choice and individual accountability.

To use the words of US billionaire Warren Buffet:

There’s a class war, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.

The current stagnation of wages we are seeing in Australia is no accident and no mystery. It’s the result of the intentional erosion of worker power (largely due to the successful campaign to demonise unions) and the end of the bipartisan federal government commitment to full employment.

The impact of full employment on wages is profound. The greatest bargaining chip a worker has is to withdraw their labour.

When it’s difficult to get a new job, unemployment benefits are well below the poverty line and the unemployed are demonised by politicians and the media alike, workers are much less inclined to push hard for improved wages or conditions.

I’m not arguing that we could simply adopt the policies of 1945 and magically return to the golden years of the 50s and 60s; Australia is a very different country and too much has changed. However, we can learn a great deal from the 1945 white paper in terms of ambition, commitment, and the embrace of complexity and nuance.

The federal government could restore its commitment to creating full employment in Australia, using its spending power to make up for any shortfall in private jobs as it did during the post-war boom. History demonstrates that the careful and coordinated use of both fiscal policy (spending and taxing), and monetary policy (interest rates) to manage the economy can create a more prosperous and egalitarian Australia.

It’s well past time for a 21st century update to the 1945 white paper on full employment.

Author: Warwick Smith, Research economist, University of Melbourne