The re-election of the Morrison government has delivered an Australian housing policy platform based on home ownership. The recently announced First Home Loan Deposit Scheme and the existing First Home Super Saver Scheme complement first home buyer grants and stamp duty concessions from state and territory governments. What we aren’t going to see is a major increase in the supply of affordable housing through a dedicated subsidised affordable rental program or negative gearing and capital gains tax reform.

Is a policy based on home ownership going to fix the problems of housing affordability in this country? The BCEC Housing Affordability Report published today by the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre suggests not.

The report is based on a survey that collected responses from just over 3,600 Australians across three states – New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia – with 75% of responses from metropolitan locations and 25% from regional areas.

Similar surveys were conducted in 2015 and 2017. This allows for comparisons across the three periods.

Housing costs

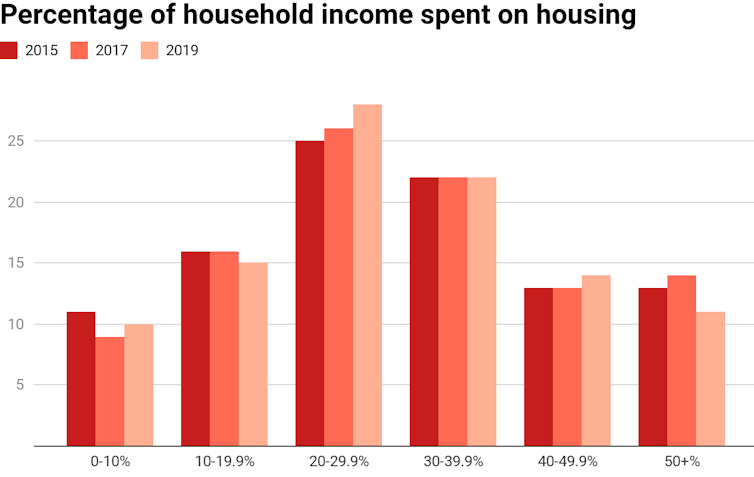

The survey asked respondents to estimate the proportion of their gross income spent on housing costs. Around 40% of all households reported living rent/mortgage-free (outright owners, young adults living with parents etc). The chart below shows the distribution across six bands for the remaining households.

Just under half reported paying over 30% of their income on rent or mortgage costs. We see little change over the three surveys, although slightly fewer households are now paying more than 50%.

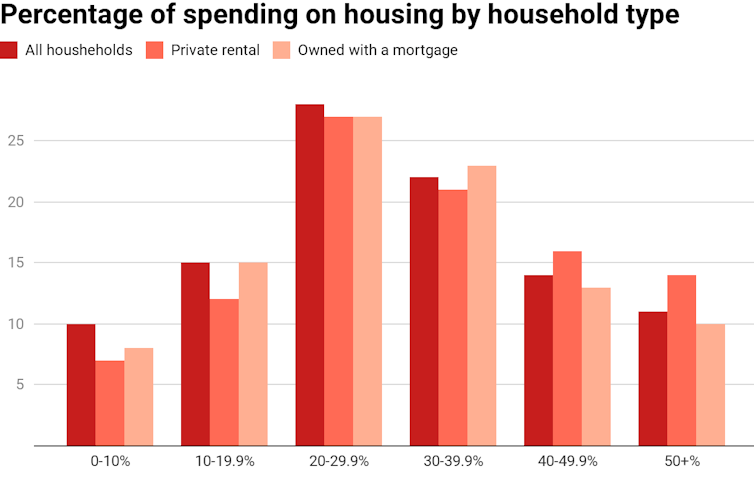

For 2019, slightly more private renters pay over 30% compared to owners with a mortgage, but renters are more likely to be in the highest burden groups. The main difference is 60% of renters are forced to take on these high housing costs while 72% of owners take them on by choice.

Households are very sensitive to changes in housing costs: 40% of those surveyed said a 10% increase in costs would have a major impact on their financial position. The expected impact was greater for renters than owners with a mortgage (44% compared to 38%). A 3% increase in the mortgage interest rate would have a major impact on the financial position of 63% of owners.

The impact of sustaining such costs can be severe: 46% said high housing costs affected their mental health and 30% their physical health.

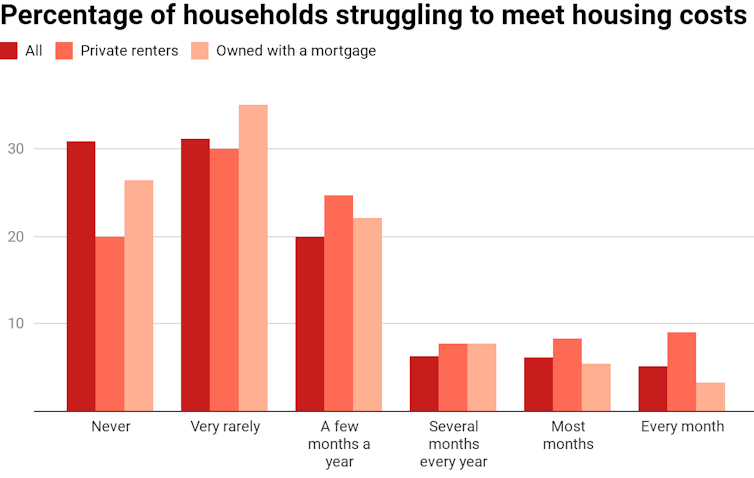

The chart below shows the proportions of households struggling to meet their housing costs. Again, we see only slight improvement across the three surveys.

Among all households, 37% reported difficulty regularly meeting housing costs (at least a few months a year). This rose to around half of all renters and low-income households and to 56% of one-parent families.

Perceptions of affordability

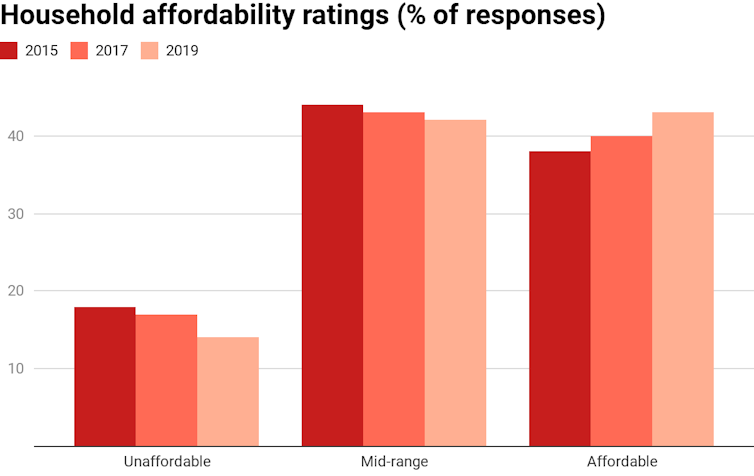

Housing affordability is not just about paying the rent or mortgage. It also includes running costs such as utility bills and maintenance. The survey asked respondents to rate the affordability of their housing on a ten-point scale and the results were collated into three ranks.

The chart below shows some improvement across surveys in the proportions of households rating their housing as affordable. These households are largely outside the lower-income groups.

Policy settings

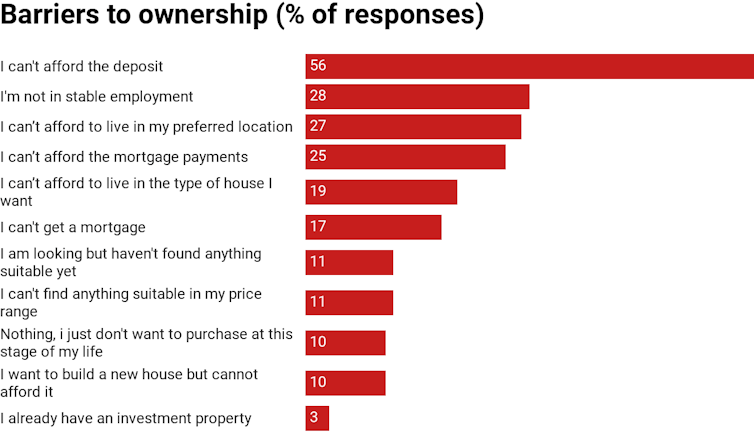

The deposit gap is the biggest barrier for potential home buyers, almost double the importance of the next barrier – a lack of stable employment. Other barriers largely revolve around a lack of suitable stock.

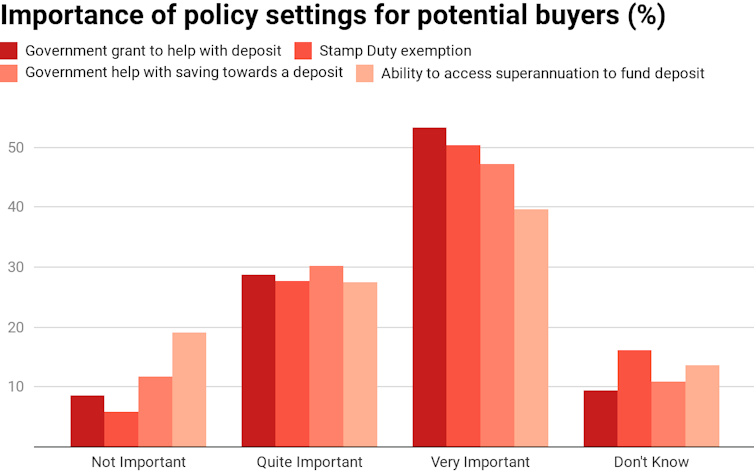

Help for first home buyers is now embedded. Around three-quarters of potential purchasers regard government help through the various mechanisms shown in the chart below as quite or very important while two-thirds would like access to their superannuation to fund a deposit.

For those without help from the “bank of mum and dad” these policies can mean the difference between home ownership and many more years living with parents or renting. It is difficult to see how such help can be equitably removed from the housing system.

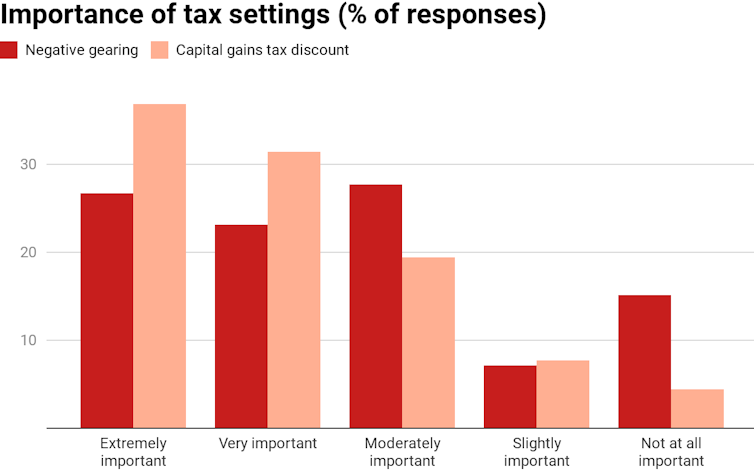

The survey included a number of questions for respondents owning an investment property and for those thinking about buying one. The capital gains tax (CGT) discount was more important to investors that negative gearing. However, only 15% regarded the latter as unimportant.

Around a quarter of investors said they wouldn’t have bought their property if negative gearing were not available and CGT was half its current rate. And 28% said they would not buy an investment property in the absence of negative gearing.

Such results suggest a modest impact on investment demand which could impact on local housing markets, depending upon the balance between investors and owner-occupiers in those markets.

Policy development

Between the 2017 and 2019 surveys, house prices and rents fell in large areas of the three states. Yet our analysis shows little impact on affordability for low-income households. Intervention is required to deliver housing affordable to such households.

Investment in the National Housing Financial Investment Corporation (NHFIC) and the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA) provides some hope outside home ownership policies. The NHFIC has a major role to play in securing funding for the community housing sector. Let’s hope it does not get sidetracked in its new role delivering the first home buyers deposit guarantee scheme.

Large numbers of households are struggling with their housing costs, and not meeting these costs can result in homelessness. This points to the need for more investment in public and community housing.

Ultimately, there is a mismatch between incomes and house prices. Major housing system reform is necessary to redress the balance.

In the meantime, a large and sustained supply of subsidised rental housing and a secure private rental sector that offers a real alternative to ownership are essential components of any future Australian housing system.

Authors: Steven Rowley, Director, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Curtin Research Centre, Curtin University; Alan Duncan, Director, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, and Bankwest Research Chair in Economic Policy, Curtin University; Amity James, Senior Lecturer, School of Economics, Finance and Property, Curtin University