In the just released Bank for International Settlements report, there is some interesting comparative country data on banks around the world, relative to the big four in Australia.

Such comparisons are always fraught with difficulty, as definitions may vary, but they also show trends over recent years, so we can look across the years too.

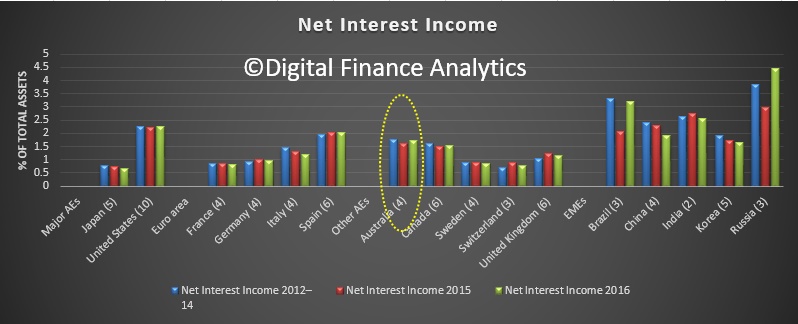

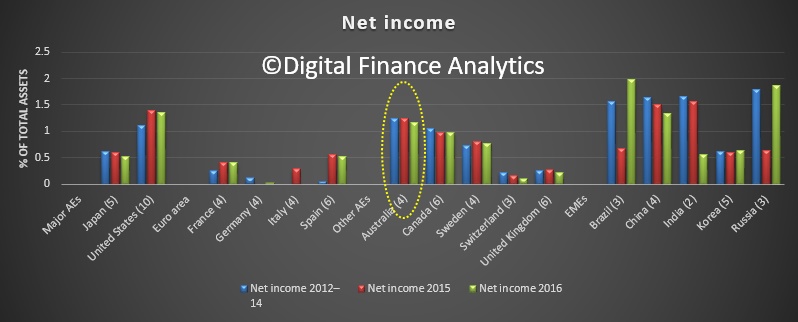

These charts make relative comparisons against total assets held. Australian banks are generating high returns on assets, compared with many advanced economies, though US banks are roaring back as conditions there improve.

Within income, net interest income is relatively higher compared with the UK, and many other European centres, though lower than USA.

Within income, net interest income is relatively higher compared with the UK, and many other European centres, though lower than USA.

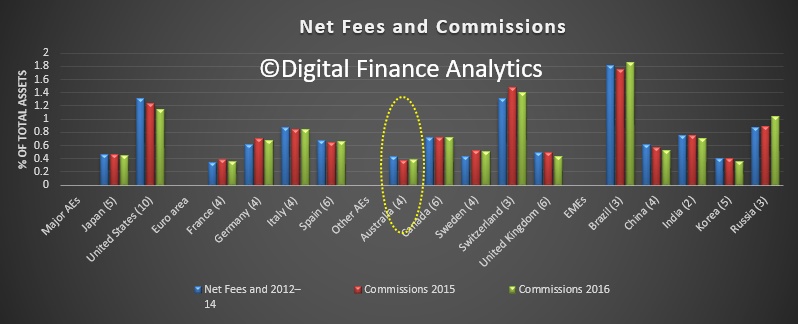

Fees and commissions are relatively lower because Australian banks have lower investment banking income.

In recent years, bank profitability has been hamstrung by tepid economic growth, low interest rates and relatively muted client activity. Yet, with the global recovery maturing and monetary policy in key jurisdictions poised for a gradual tightening, the outlook for banks’ bottom line is now improving. This underlines the need for banks to use the “growth dividend” of dissipating headwinds to complete the adjustment of their business models to the post-crisis reality.

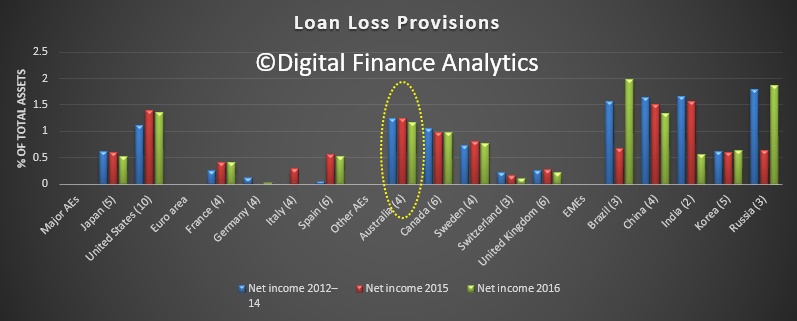

Conjunctural factors continued to be a drag on profitability, even though the impact varied across regions. Net income, for example, remained well below pre-Great Financial Crisis (GFC) levels. Relative to total assets, it hovered around zero across much of Europe and was only slightly higher in many other jurisdictions, including key emerging market economies (EMEs). Past years of low and declining interest rates had eroded yields on earning assets. Even though interest expenses also declined, assets typically repriced more quickly, weighing on net interest income. Revenue from fees and commissions and other capital market activities also remained subdued. That said, corporate bond issuance and merger and acquisition (M&A) activity supported bank revenues in jurisdictions such as the United States.

There are now signs that conjunctural headwinds are receding. To the extent that economic activity continues to strengthen, higher interest rates and rising term spreads should support intermediation margins. Stronger demand for banking services and higher capitalisation levels, in turn, should underpin business volume and balance sheet expansion. And both revenue growth and capital buffers would help cushion any interest rate-driven valuation losses on securities portfolios. Post80 BIS 87th Annual Report crisis declines in interest rates have increased the duration of outstanding securities, making unhedged fixed income positions vulnerable to mark-to-market losses. Such pressures could be particularly pronounced in a context of tightening US dollar funding conditions (see below).

Individual banks’ ability to benefit from the improved macroeconomic backdrop and rising interest rates depends on a number of factors. One is asset composition: revenue growth is driven by the rollover of maturing fixed rate assets and loans and, hence, depends on the share of fixed rate versus floating rate assets.

On the liabilities side, core deposits are known to be relatively price-insensitive. Since they are a key funding source for many banks, increases in funding costs generally lag those in short-term rates. In addition, moderately stronger economic growth and higher rates tend to boost client activity across several business lines.

Indeed, starting in mid-2016 capital market revenues benefited from higher market volatility after the Brexit referendum and in anticipation of US policy rate action

Another factor is asset quality. This should generally improve as GDP growth picks up, unemployment declines and rising demand supports the corporate sector.

In most advanced economies, expectations are that this will help non-performing loans (NPLs) to level off and ultimately decline. That said, banking systems in some jurisdictions still look vulnerable to a further deterioration in credit quality. In a number of euro area countries, for example, the share of NPLs remains stubbornly high. Structural factors, such as ineffective legal frameworks and defective secondary markets for NPLs, have been hindering the resolution of problem loans.

The outlook for asset quality becomes more differentiated once countries’ position in the financial cycle is considered. Standard metrics, such as credit-to-GDP gaps, signal financial stability risks in a number of EMEs, including China and other parts of emerging Asia. Gaps are also elevated in some advanced economies, such as Canada, where problems at a large mortgage lender and the credit rating downgrade of six of the country’s major banks highlighted risks related to rising consumer debt and high property valuations.2 While banks’ NPL ratios in all these countries mostly remained low, a majority of EMEs have continued to see financial booms, flattering credit quality indicators. Thus, loan performance should be expected to deteriorate once the financial cycle turns. In addition, pressures could also emerge as a result of spillovers from tighter US monetary policy. In some Asian economies, for example, non-financial corporates took advantage of easy global financing conditions to leverage up in US dollars. Many of these corporates may thus find themselves unhedged and exposed to currency mismatches if their domestic currencies depreciate. Any balance sheet strains, therefore, could ultimately feed into banks’ credit risk exposures.