Interesting research from the US, which shows that households who get into financial difficulty may make up a minority of all households, but they tend to stay in this state for an extended period. This is exacerbated by high default fees and charges, and an impatience to consume.

When households lose income unexpectedly, they may skip debt payments (such as credit card payments) rather than lower their consumption. Given that most everyone will experience unanticipated income changes at some point, one may expect that a majority of households fell (at least temporarily) into financial distress sometime between 1999 and 2016. The findings in this post challenge that view: The data show financial distress to be highly concentrated in a relatively small share of the population.

Measuring Financial Distress

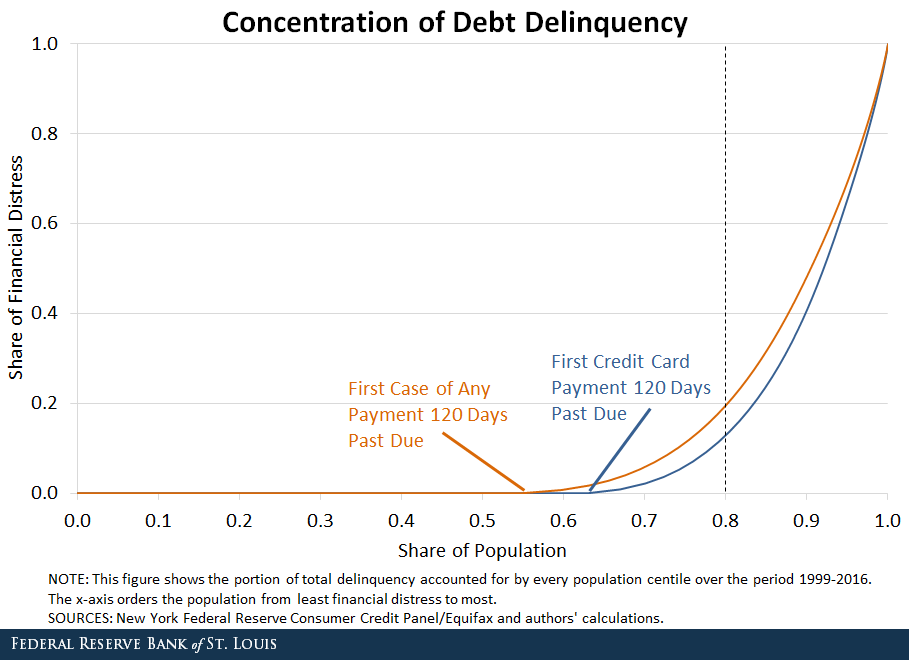

We used data from the New York Federal Reserve Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax to show the concentration of debt delinquency across a nationwide sample of people with credit reports. “Total delinquency” refers to the total number of quarters in which people in our sample had debt payments that were 120 days delinquent or more.

The graph below orders the population from least financial distress to most and presents the portion of total delinquency accounted for by every population centile. This is done in two separate lines for credit card debt and for any kind of debt.1

Debt Delinquency Concentration

The first major fact to emerge is that debt delinquency was highly concentrated over the period 1996-2016. About 60 percent of people never have debt payments 120 days late. On the other extreme, 20 percent of people accounted for 80 percent of financial distress, and around 10 percent of people accounted for 50 percent.

This points to the fact that delinquency is frequent among those who experience it. In fact, more than 30 percent of people who had debt 120 days delinquent at any point in our sample spent at least a quarter of their time in that state.

Effect of Credit Card Delinquency

A second major fact to emerge is that much of the trend in financial distress concentration was driven by credit card delinquency. This makes sense given that credit cards are a widely used debt instrument.

Addressing Financial Distress

In light of the remarkable concentration and persistence of financial distress, it is important for policymakers to be able to disentangle the causes. What factors drive some people to be in financial distress for so long and others to never experience it?

In a working paper titled “The Persistence of Financial Distress,” Fed economists Juan M. Sánchez, José Mustre-del-Río and Kartik Athreya examined this question.2 Specifically, they showed that while traditional economic models of defaultable debt cannot account for the observed concentration and persistence of financial distress, a model which also accounts for high penalty rates on delinquent debt and individuals’ heterogeneity in impatience to consume can do so with a high degree of accuracy.