From The St. Louis Fed Economic Synopsis.

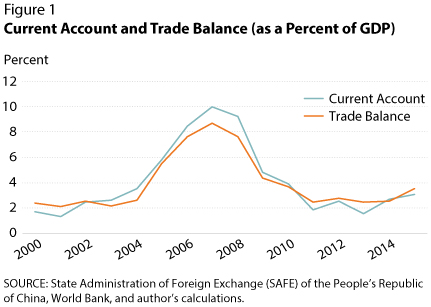

China has been running a current account surplus since 2000, which has been a policy issue regarding exchange rates and currency manipulation. A current account surplus means that China has been a net lender to the rest of the world. China’s current account surplus reached 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007 and then started to decline until 2011, when it fell to 1.8 percent of GDP. The current account surplus has been stable since then, with a slight tendency to increase in more recent years. In particular, in 2015, the current account was around 3 percent of China’s GDP, but it has not returned to the high levels reached in 2007. What are the main factors behind the decline?

The current account is composed of three main categories: (i) the trade balance (net earnings on exports of goods and services minus payments on imports of goods and services); (ii) the net income to foreign factors (compensation of employees, investment income); (iii) and transfers.

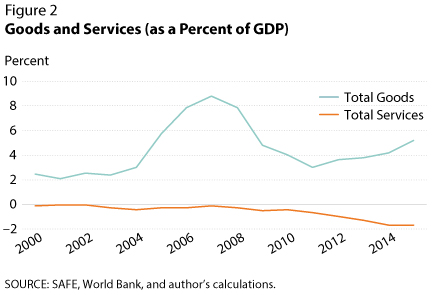

In China’s case, the main component behind the current account trend is a decline in its trade surplus. A trade surplus indicates that China has been earning more on its exported goods and services than it has been paying for its imports (i.e., it has had positive net exports). As Figure 1 shows, net exports in China, as a percentage of GDP, closely track the current account and have been declining since 2007. Indeed, the trade surplus was around 9 percent of GDP in 2007 and fell to 3.5 percent of GDP in 2015. This decline has been driven by both a decline in the surplus of traded goods and an increase in the deficit of traded services (Figure 2). However, the goods surplus has picked up again since 2011, while the services deficit has become more pronounced. Interestingly, trade in services was roughly balanced between 2000 and 2007 and later became a deficit, reaching around –1.7 percent of GDP by 2015. Thus, even though the value of China’s exported goods has exceeded the costs of its imports, China has been importing more services than it has been exporting. Even more interesting is the fact that the increase in China’s services deficit has prevented its current account surplus from rising despite the increased trade surplus in goods.

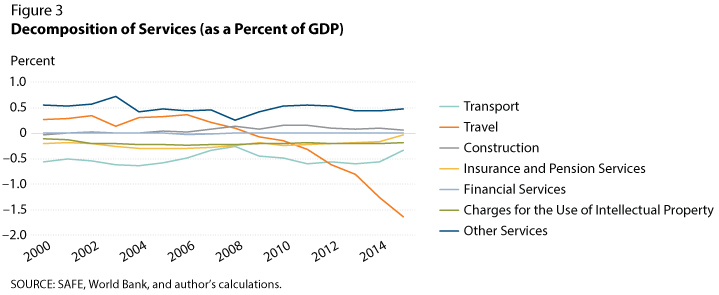

Figure 3 shows the main categories of China’s international trade in services. One category stands out: travel services, which includes mainly tourism. China’s increasing services deficit has been driven mainly by overseas tourism- related consumption. According to a recent report, two population groups in China have been driving tourism: Millennials (young people 15 to 35 years of age) and a growing middle class. The report indicates two primary reasons for increased tourism by these two groups. On the one hand, young people travel for exposure to overseas experiences. On the other hand, Chinese travel for shopping, which accounted for 30 percent of overseas Chinese spending in 2015. The prime shopping destination currently is Hong Kong, but new destinations such as Japan, Korea, and Europe are expected to become increasingly popular.

Overall, the increasing trade deficit in services, spurred mainly by the rise in tourism, seems to be an important factor in the recent trend in China’s current account. As a result, the current account surplus is increasing only slightly despite a larger increase in net exported goods in recent years. What factors could change this trend? Fluctuations in exchange rates in the main destinations for Chinese tourists could affect tourism. For instance, a depreciation of the yuan could slow the increase in the travel services deficit while concurrently increasing the earnings in exports of goods—all of which could generate a larger current account surplus.