The latest OECD report on inequality was released today. The richest 10% of the population now earn 9.6 times the income of the poorest 10%; this ratio is up from 7:1 in the 1980s, 8:1 in the 1990s and 9:1 in the 2000s. Tight fiscal conditions have resulted in social spending cuts, including in areas targeted to the most disadvantaged. In 2012, the bottom 40% owned only 3% of total household wealth in the 18 OECD countries which have comparable data. By contrast, the top 10% controlled half of all total household wealth and the wealthiest 1% held 18%! Wealth is considerably more concentrated than income, exacerbating the overall disadvantage of low-income households.

At the launch, Angel Gurría, Secretary-General, OECD said:

At the launch, Angel Gurría, Secretary-General, OECD said:

For years now we have been underlining the toll that inequality takes on people’s lives. And I am proud of the contribution that the OECD has made in recent decades, putting inequality at the heart of the political and economic debate. Our 2008 report, Growing Unequal? sounded the alarm on the long-term rise in income inequality; and in 2011 Divided We Stand sought to diagnose the root causes that lay behind it.

But now we need to move the conversation forward. This is why today we are launching our new report In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All in which we underline the toll that ever-rising inequality takes on people’s lives and the wider economy. But more than that, this report proposes concrete policy solutions to promote opportunities for more inclusive growth.

Where we stand: Trends in inequalities

Let me first remind you of the scale of the challenge. The latest data from In It Together make for stark reading. The richest 10% of the population now earn 9.6 times the income of the poorest 10%; this ratio is up from 7:1 in the 1980s, 8:1 in the 1990s and 9:1 in the 2000s.

During the early years of the crisis, redistribution via tax and transfer systems was reinforced in many countries. But now it is weakening again; tight fiscal conditions have resulted in social spending cuts, including in areas targeted to the most disadvantaged.

Even in those emerging economies where inequality has fallen, like Chile or Brazil, inequality remains at staggeringly high levels (26.5:1 in Chile and 50:1 in Brazil).

The story behind wealth is even worse. In 2012, the bottom 40% owned only 3% of total household wealth in the 18 OECD countries which have comparable data. By contrast, the top 10% controlled half of all total household wealth and the wealthiest 1% held 18%! Wealth is considerably more concentrated than income, exacerbating the overall disadvantage of low-income households.

The situation is economically unsustainable

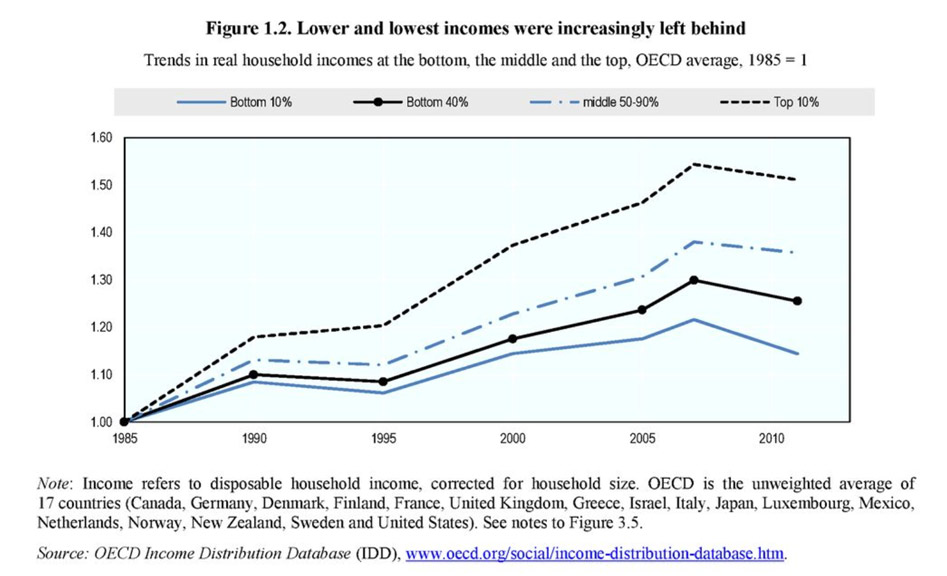

In It Together finds compelling evidence that high inequality harms economic growth. The rise in inequality observed between 1985 and 2005 in 19 OECD countries knocked 4.7 percentage points off cumulative growth between 1990 and 2010. And what matters for growth is not just the poorest falling behind. In fact, it is inequality affecting lower-middle and working class families. We need to focus much more on the bottom 40%; it is their losing ground that blocks social mobility and brings down economic growth.

We have reached a tipping point. Inequality can no longer be treated as an afterthought. We need to focus the debate on how the benefits of growth are distributed. Our work on inclusive growth has clearly shown that there doesn’t have to be a trade-off between growth and equality. On the contrary, the opening up of opportunity can spur stronger economic performance and improve living standards across the board!

Policies to promote inclusive growth

In It Together identifies four key policy areas to promote opportunities for more inclusive growth.

First, to increase equality of opportunity and boost our economies it will be absolutely essential to enhance women’s participation in economic life. Overcoming gender inequalities is vital to improving long-term growth prospects and has a profound impact on inequality. If the share of households with a working woman had remained at the levels of the early 1990s, the rise in income inequality would have been almost 1 Gini point higher, on average. And the fact that more women have worked full-time and earned higher wages since 1990 has limited the rise of inequality by an additional Gini point. But we cannot be happy with the slow pace of change.

Governments should be asking themselves whether they can afford to waste the potential of the many women who are excluded from the labour market. To help women make the best use of their talents, we need to make good quality and affordable childcare available and also encourage more fathers to take parental leave.

Second, labour market policies need to address working conditions as well as wages and their distribution. Before the crisis, employment was at record highs in many OECD countries but inequality was rising. The increase in non-standard work was one of the culprits. In 2013, about a third of total OECD employment was in non-standard work, with about equal shares of temporary jobs, permanent part-time jobs and self-employment. Youth are the most affected group: 40% are in non-standard work and about half of all temporary workers are under 30.

Non-standard jobs are not always bad jobs, but work conditions are often precarious and poor. Low-skilled temporary workers, in particular, have much lower and unstable earnings than permanent workers. This would be less troubling if non-standard jobs were simply stepping stones to better and well-paying careers. But for the young, the part-time or self-employed worker this is often not the case. And among those on temporary contracts in a given year, less than half had full-time permanent contracts three years later.

The challenge is therefore not only the quantity, but also the quality of jobs. Better social dialogue and improved work conditions across the income range are crucial elements of an inclusive employment strategy.

Third, we cannot afford to neglect the education and skills of any part of our societies. A focus on education in early years is essential to give all children the best start in life. This investment needs to be continued throughout the life cycle to prevent disadvantage, promote better opportunities and educational attainment.

In it Together provides new evidence that high inequality makes it harder for lower-middle and working class families to invest in education and skills. An increase in inequality of around 6 Gini points reduces the time children from poorer families spend in education by about half a year. And it also lowers the probability of poorer people graduating from university by around four percentage points. This leads to an ever widening gap in education and life-time earnings.

Last but not least, governments should not hesitate to use taxes and transfers to moderate differences in income and wealth. There has been a fear that redistribution damages growth and this has led to a long-term decline in redistribution in many countries. Our work suggests that well-designed, prudent redistribution need not harm growth. As top earners now have a greater capacity to pay taxes than before, governments should ensure that they pay their fair share of the tax burden.

We do not need new instruments, we simply need to use the ones we have: scaling back tax deductions, eliminating tax exemptions, increasing marginal tax rates, using property taxes and above all, ensuring greater tax compliance. And let’s not forget government transfers. They play an important role in guaranteeing that low-income households do not fall too far behind.

Ladies and gentlemen, ever rising inequality can be avoided. It is for us to re-imagine and create our economies anew, so that each and every citizen regardless of income, wealth, gender, race or origin is empowered to succeed.

Governments around the world need to take decisive action to promote inclusive growth. In that spirit, I urge each and every country to recognise that when it comes to economic prosperity we are not in it alone, we are “In It Together”.