Electronic trading has become an increasingly important part of the fixed income market landscape in recent years. As a result there are a number of risks to consider and regulatory issues to address, according to a newly released report from the Bank For International Settlements Markets Committee.

The growth in electronic trading as, according to the report, contributed to changes in the market structure, the process of price discovery and the nature of liquidity provision. The rise of electronic trading has enabled a greater use of automated trading (including algorithmic and high-frequency trading) in fixed income futures and parts of cash bond markets.

The term “electronic trading” covers a variety of activities that are part of the life cycle of a trade. In this report, electronic trading refers to the transfer of ownership of a financial instrument whereby the matching of the two counterparties in the negotiation or execution phase of the trade occurs through an electronic system.

Electronic trading broadly covers: trades conducted in systems such as electronic quote requests, electronic communications networks or dealer platforms; alternative electronic platforms such as dark pools; the quotation of prices or the dissemination of trade requests electronically; and settlement and reporting mechanisms that are electronic. For example, this includes both high-frequency trading on exchanges and trades negotiated by voice but executed and settled electronically.

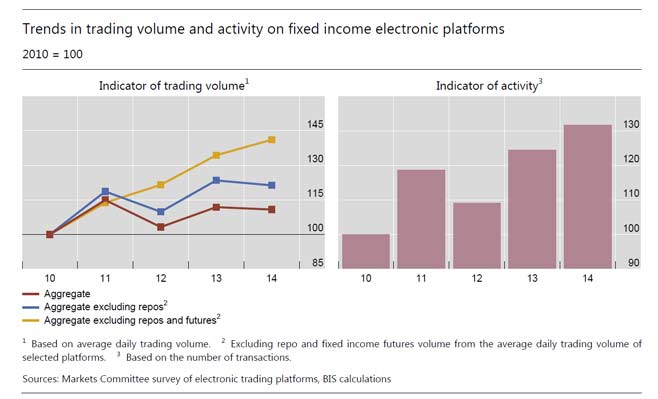

The electronification of all these aspects of fixed income trading has been steadily increasing. There are now a variety of electronic trading platforms (ETPs), systems that match buyers with sellers, that differ in terms of the composition of their clients and their trading protocols.

Innovative trading venues and protocols (reinforced by changes in the nature of intermediation) have proliferated, and new market participants have emerged. For some fixed income securities, “electronification” has reached a level similar to that in equity and foreign exchange markets, but for other instruments the take-up is lagging.

Innovative trading venues and protocols (reinforced by changes in the nature of intermediation) have proliferated, and new market participants have emerged. For some fixed income securities, “electronification” has reached a level similar to that in equity and foreign exchange markets, but for other instruments the take-up is lagging.

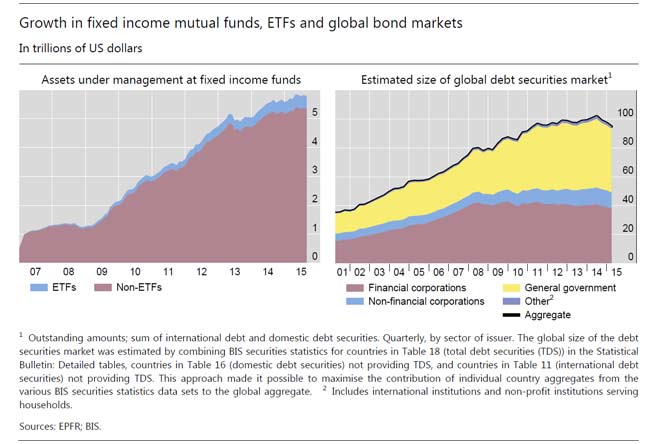

Electronic trading in fixed income markets has been growing steadily. In many jurisdictions, it has supplanted voice trading as the new standard for many fixed income asset classes. Electronification, ie the rising use of electronic trading technology, has been driven by a combination of factors. These include: (i) advances in technology; (ii) changes in regulation; and (iii) changes in the structure and liquidity characteristics of specific markets. For some fixed income securities, electronification has reached a level similar to that in equity and foreign exchange markets. US Treasury markets are a prime example of a highly electronic fixed income market, in which a high proportion of trading in benchmark securities is done using automated trading. However, fixed income markets still lag developments in other asset classes due to their greater heterogeneity and complexity.

Electronic trading in fixed income markets has been growing steadily. In many jurisdictions, it has supplanted voice trading as the new standard for many fixed income asset classes. Electronification, ie the rising use of electronic trading technology, has been driven by a combination of factors. These include: (i) advances in technology; (ii) changes in regulation; and (iii) changes in the structure and liquidity characteristics of specific markets. For some fixed income securities, electronification has reached a level similar to that in equity and foreign exchange markets. US Treasury markets are a prime example of a highly electronic fixed income market, in which a high proportion of trading in benchmark securities is done using automated trading. However, fixed income markets still lag developments in other asset classes due to their greater heterogeneity and complexity.

The report highlights two specific areas of rapid evolution in fixed income markets. First, trading is becoming more automated in the most liquid and standardised parts of fixed income markets, often importing technology developed in other asset classes. Traditional dealers too are using technology to improve the efficiency of their market-making. And non-bank liquidity providers are searching for ways to trade directly with end investors using direct electronic connections. Second, electronic trading platforms are experimenting with new protocols to bring together buyers and sellers.

Advances in technology and regulatory changes have impacted the economics of intermediation in fixed income markets. Technology improvements have enabled dealers to substitute capital for labour. They are able to reduce costs by automating quoting and hedging of certain trades. Dealers are also able to better monitor the trading behaviour of their customers and how their order flow changes in response to news. Dealers are internalising flows more efficiently across trading desks, providing greater economies of scale for trading in securities where volumes are particularly high. But the growth in electronic trading is posing a number of challenges for traditional dealers. It has allowed new competitors with lower marginal costs to reduce margins and force efficiency gains, and it has required a large investment in information technology at a time when traditional dealers are cutting costs.

Electronification is also changing the behaviour of buy-side investors. They are deepening their use of execution strategies, in particular complex algorithms. Large asset managers are further internalising flows within their fund family. And a number of asset managers are supporting different competing platform initiatives that are attempting to source pools of liquidity using new trading protocols. Electronic trading tends to have a positive impact in terms of market quality, but there are exceptions. There is relatively little research specific to fixed income markets, but lessons can be drawn from other asset classes. Evidence predominantly suggests that electronic trading platforms bring advantages to investors by lowering transaction costs. They improve market quality for assets that were already liquid by increasing competition, broadening market access and reducing the dependence on traditional market-makers. But platforms are not the appropriate solution for all securities, particularly for illiquid securities for which the risks from information leakage are high. For these securities, there is still a role for bilateral dealer-client relationships.

The impact of automated and high-frequency trading is a matter of considerable debate. Studies suggest that automation results in faster price discovery and an overall drop in transaction costs (at least for small trade sizes). The entrance of principal trading firms with lower marginal costs than traditional market-makers has intensified competition. It remains to be seen whether the benefits of automation observed in normal trading periods also prevail during periods of stress, when the benefits of immediacy are particularly high. Competition over speed might displace traditional broker-dealers who may be more willing to bear risks over longer horizons. There is a risk that liquidity may have become less robust and prices more sensitive to order flow imbalances. Some recent episodes covered in this document shed some light on these issues. These episodes highlight that multiple drivers are likely to be at play, rather than conclusive evidence pointing to a predominant impact of automated trading alone. Electronic trading, and in particular automated trading, poses a number of challenges to policymakers. The appropriate response may differ across jurisdictions because of the heterogeneous nature of fixed income markets as well as the varying degrees of electronification.

The report identifies four core areas for further policy assessment:

- First, the steady advance of electronic trading needs to be appropriately monitored. Access to better data is required. A supplement to better monitoring is to establish regular dialogue between regulatory bodies and industry participants.

- Second, further investigation is required to gauge the impact of automated trading on market quality. While there has been an improvement in certain metrics, liquidity may have become more fragile during stress episodes. More sophisticated measures need to be used to capture the multiple dimensions of market quality.

- Third, electronification has created additional challenges for risk management at market-makers, platform providers and end investors. Algorithm developers should follow guidelines for best practices. Policymakers should be conscious of the growing dependence on critical electronic trading infrastructures.

- Fourth, regulation and best practice guidelines should be living documents. They should be repeatedly reviewed and adapted as markets evolve. It may also be worth considering whether current regulatory requirements contribute to a level playing field amid the changing market structure and/or whether, for example, a code of conduct applicable to all significant market participants may be appropriate, when warranted by the specific circumstances.

When responding to these challenges, regulators should strike a balance between prescription and room for healthy innovation in market design. A flexible approach can enable platforms to compete to discover new ways to increase efficiency and integrity.