On Friday submission to the Royal Commission into Financial Service Misconduct relating the the draft report closes. You can still make a Public Submission – a quick and painless process, and it is a once in a generation chance to shape the future of finance in Australia.

This is what DFA did today, and here is a copy of what I said.

Summary

We welcome the findings from the draft report and recommend the following policy options.

- The culture in the finance sector needs to change, to put the customer first. Mortgage brokers for example should have a best interest duty and commissions should be banned.

- The current focus on “financial stability” is myopic, favouring large players, over small, and building structural risks into the system; the regulators have failed.

- The large players are too big to fail and too complex to manage, and need to be broken apart. A modern Glass Steagall separation would achieve this, and is proven to reduce risk, and drive better customer outcomes and right size our finance sector.

- The existing regulatory structure, operating in the Council of Financial Regulators needs to be changed, as its narrow focus on financial stability, and a massive “bet” on inflating the housing sector now at risk. None of the regulatory actors are without blame.

Introduction.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) is an Australian boutique research, consulting and advisory firm which combines primary consumer and small business research, analysis of both private and public datasets and economic modelling to analyse the dynamics of the finance and property sector. We have been operating since 2005.

Our analysis is based on a rolling 52,000 household survey, with more than 4,000 new data points added each month. From this we are able to assess the state of household finances, their future property transaction intentions, and their level of debt; and ability to service it.

Our analysis is based on a rolling 52,000 household survey, with more than 4,000 new data points added each month. From this we are able to assess the state of household finances, their future property transaction intentions, and their level of debt; and ability to service it.

Households Are Overextended

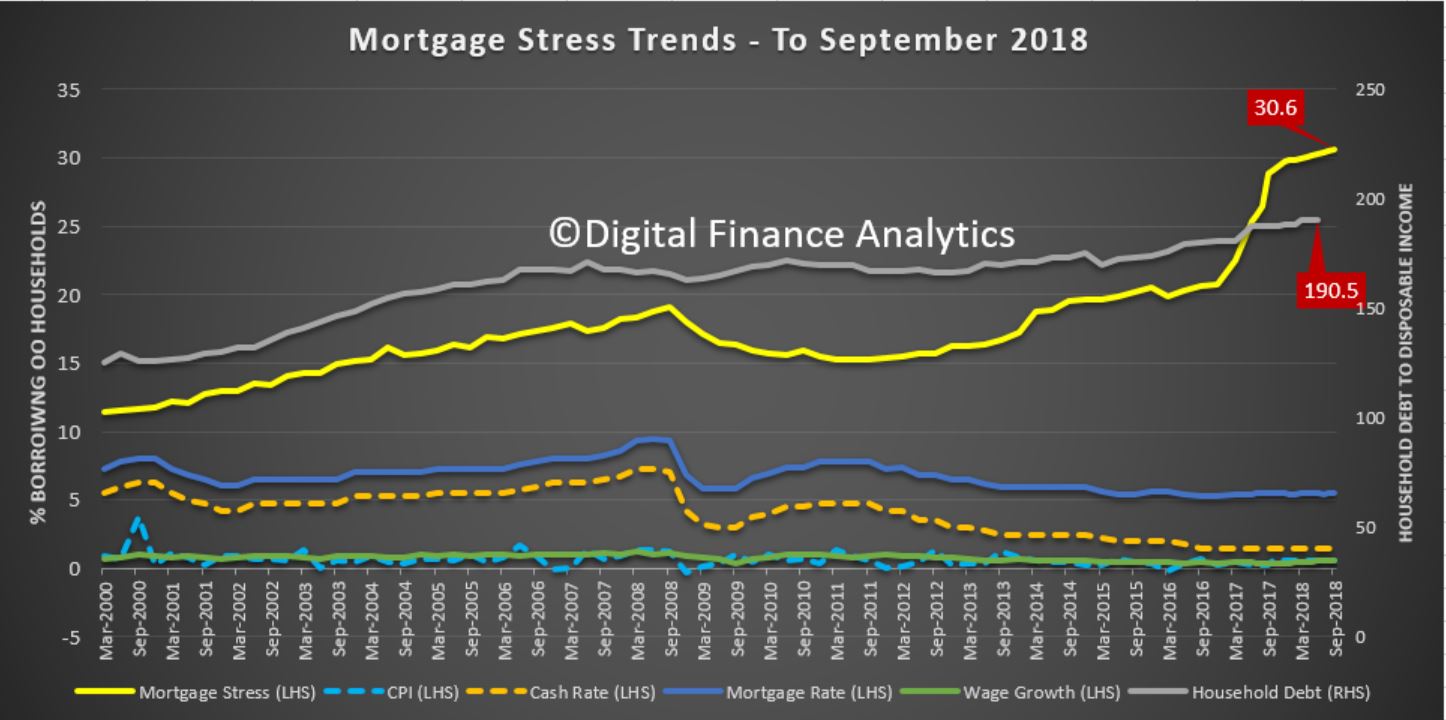

We have observed a considerable expansion of household debt in recent years, driven by low interest rates, more generous lending standards, and some degree of “not suitable” lending and fraud. The RBA reports that the household debt to income ratio is now around 190 and the debt to GDP ratio is one of the highest in the world.

As a result, more households are in financial stress, as tracked in our mortgage stress trends (defined in cash flow terms, not a set percentage), and last month more than one million households with owner occupied mortgages were in difficulty, despite the ultra-low interest rates. This equates to 30.6% of all borrowing households.

This has been exacerbated by flat incomes, and rising costs, but poor lending practice is the underlying cause. We also believe that as interest rates rise, and property prices fall further, the financial state of households will decline further. This is because many are enjoying the “wealth effect” of property gains in recent years, but this is only a paper gain, and now prices are falling. The expectation is prices will fall further and faster.

This has been exacerbated by flat incomes, and rising costs, but poor lending practice is the underlying cause. We also believe that as interest rates rise, and property prices fall further, the financial state of households will decline further. This is because many are enjoying the “wealth effect” of property gains in recent years, but this is only a paper gain, and now prices are falling. The expectation is prices will fall further and faster.

The Cause of Property Price Falls

Following many years of over-free lending, the regulators have now intervened to an extent and as a result lending standards are tightening, with up to a 40% fall in borrowing power for many compared with a year ago. In the main though this is a result of the existing regulations now being applied as originally intended, rather than new laws, as incomes and expenses are being tested, as opposed to using a formula based on HEM (Household Expenditure Measures).

This resetting of lending standards marks a significant change in the market, and as a result according to our surveys, demand for property is easing, at the time when foreign buyers are receding, and property investors are getting twitchy. According to Bank of England research, property investors are significantly more likely to exit the market in a down turn compared with owner occupied borrowers.

Property investors, who have driven the market higher in recent years are choosing to exit, sometimes forced by the switch from interest only loans to principal and interest loans (estimated at around ~$120 billion per annum), of the $1.7 trillion total mortgage lending pools.

Our modelling shows that it is credit availability which pumped up property prices (and which allowed the Banks and other Lenders to growth their balance sheets, and profits) and the reverse is also true. The normalising of lending standards will rightly reduce credit, thus driving home prices and banks profitability lower. The catch here is that for more than a decade, Australia’s economic performance has been built on the back of ever greater mortgage and consumer debt, home price growth, and construction. Thus from a policy perspective Government, and the RBA will defend high levels of credit and home prices, despite the risks.

The other factor to consider is that as banks were so reliant on home lending to drive profitability, the incentives were there to over lend, bend the rules, and reward poor behaviour. They have not followed regulatory guidelines nor have they met community expectations. In a word, GREED, as your draft report shows.

The Policy Challenge

Our view is that whilst the restatement of the current lending standards will assist, there are more significant structural questions to be considered. Regulation and changes to the law alone cannot address the issues you call out.

The culture within the finance sector needs to be changed, to put customers at the centre of their business. Whilst talk is cheap however, there is little evidence of substantial change as yet. The removal of commissions should be a corner stone, as conflicted remuneration remains a significant problem. Mortgage brokers, for example, should have a responsibility to act in the best interest of their customers. The industry will resist this, but it is essential.

Currently, the capital adequacy rules favour mortgage lending relative to productive lending to business and as a result according to our Small and Medium Enterprise surveys, many businesses are unable to obtain finance (or can only do so by securing their property). We believe the various risk weights reflect a myopic view of the financial system and they need to be changed. Too much of the bank’s portfolio of loans – up to 65% – is against residential property – this is extraordinarily high by international standards, and presents a significant risk, to say nothing of the lack of business investment which has resulted.

However, we hold the view that the major financial sector players are too complex to be managed effectively, scale is now a disadvantage. Thus we believe there is a case to break up the banks into smaller units. This would involve both vertical disaggregation (separation of advice, sales and product manufacture) and horizontal disaggregation (separate of wealth, insurance, retail banking and investment banking). In addition, there are significant risks from their operations in derivatives, and in an integrated environment, costs, risks and profits are cross linked. Given the size of the derivatives sector (significantly larger than before the GFC), the systemic risks are significant. To counter this, we advocate the implementation of a modern Glass Steagall separation, where the high-risk speculative activities are separated from the normal lending, payment and deposit functions within banking. This would have the added benefit of reducing the potential risks of a bank deposit bail-in in a time of crisis. Evidence suggests that the existence of a modern Glass Steagall separation would reduce risk and limit systemic risk. In a post Glass Steagall world, bank lending would be more aligned with the deposits available, so their ability to make loans “from thin air” as in the current system would be curtailed. They would also be more inclined to make loans for truly productive purposes.

We also need to consider the role of the regulators and the RBA. Murray’s Financial System Inquiry recommended that the effectiveness of the current regulatory system be monitored. The Council of Financial Regulators is the peak body, chaired by the RBA, where key policy is set, with the Treasury, ASIC, APRA and others. However, none of their deliberations are made public, and it appears that all entities have been sharing the same view that growing housing credit was the chosen growth lever of choice following the mining boom. It appears that the weak supervisory approach from ASIC and APRA stemmed from this policy, and was supported by policy rates being set too low. As a result, the systemic risks have been underestimated, and the economic platform for the country narrowed.

We believe that there should be a stronger advocate for the consumer within the regulatory system, perhaps the ACCC should take this role. But more broadly the role of individual regulators and how they connect needs clarity. The Royal Commission highlighted the lack of coherence, and alignment. We also would argue (perhaps beyond the scope the current inquiry) that APRA has myopically focussed on financial stability, at the cost of good consumer outcomes and competition, that the regulations favour large players over small players, that the RBA policy rates are too low, and the ASIC so far is still perceived as a weak and ineffective regulator. Thus the area of appropriate and effective regulation is critical.