Moody’s says analysts from a major bank believe that reducing the top corporate income tax rate from 35% to 20% will slow the average annual increase of US industrial company debt over the next 10 years from nearly 5% without a tax cut to roughly 2% with the tax cut.

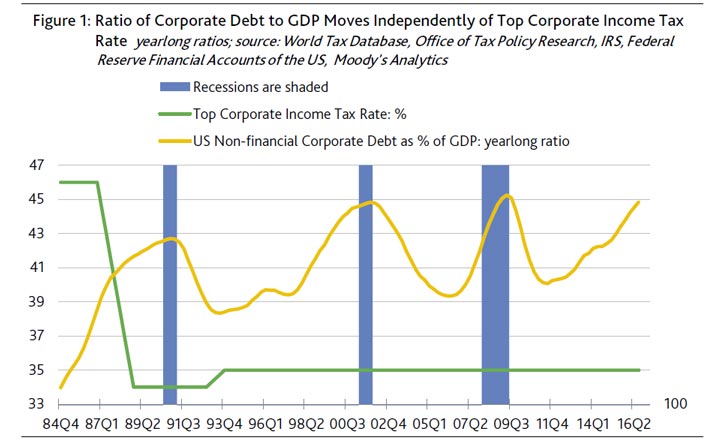

However, what happened after the slashing of the top corporate income tax rate from 1986’s 46% to 1987’s 40% and, then, to 1988’s 34% questions whether prospective tax cuts will more than halve the growth of corporate debt over the next 10 years.

Nevertheless, business borrowing is likely to be noticeably lower if business interest expense is no longer tax deductible. Such tax-reform induced reductions in business borrowing will be most prominent among very low grade credits and during episodes of diminished liquidity, extraordinarily wide yield spreads for medium- and low-grade corporates, and exceptionally high benchmark borrowing costs.

The top corporate income tax rate probably will be cut from i 35% to either the 20% proposed by House Republicans or to the 15% offered by Trump’s team. Assuming, for now, the continued tax deductibility of corporate interest expense, a lower corporate income tax rate increases the after-tax cost of corporate debt. However, a reduction by the corporate income tax rate may add enough to after-tax income to more than offset the burden of a higher after-tax cost of debt. In addition, today’s relatively low corporate borrowing costs will mitigate the increase in the after-tax cost of debt stemming from a lowering of the corporate income tax rate.

Corporate debt sped past GDP and revenues despite tax cuts of 1987-1988

Thus, a lowering of the top corporate income tax rate probably will not have much of a discernible effect on corporate borrowing. Despite the lowering of the corporate income tax rate from 1986’s 46% to 34% by 1988, the ratio of debt to the market value of net worth for US non-financial corporations rose from 1986’s 38.6% to a mid-1994 high of 51.1%. Moreover, from year-end 1986 through year-end 1989, non-financial corporate debt advanced by 9.6% annually, on average, which was much faster than the accompanying average annual growth rates of 7.2% for nominal GDP and 7.0% for the gross value added of non-financial corporations.The supposed de-leveraging effect of corporate income tax cuts was further challenged by how debt outran both the economy and business sales despite still elevated corporate borrowing costs. For example, Moody’s long-term Baa industrial company bond yield barely fell from 1986’s 10.73% average to the still costly 10.55% of 1987-1989, while a composite speculative-grade bond yield actually rose from 1986’s 12.44% to the 13.05% of 1987-1989.

It should be noted that the increase in the after-tax cost of debt was greater following 1987’s corporate income tax cut because of the much higher corporate bond yields of that time and yet corporate debt still grew rapidly. In stark contrast, recent yields of 4.74% for the long-term Baa-grade industrials and 5.96% for speculative-grade bonds are substantially lower, which, in turn, lessens the degree to which corporate income tax cuts discourage balance-sheet leveraging.