From The Conversation. We are used to being able to pay for things with legal tender.

Other than in special circumstances, refusing to accept cash can have legal consequences.

The Currency (Restrictions on the Use of Cash) Bill 2019 at present before the Senate seeks to make it an offence to use “too much cash” to pay your bills.

The intent is clearly stated in Section 4:

This Act places restrictions on the use of cash or cash-like products within the Australian economy. The Act imposes criminal offences if an entity makes or accepts cash payments in circumstances that breach the restrictions.

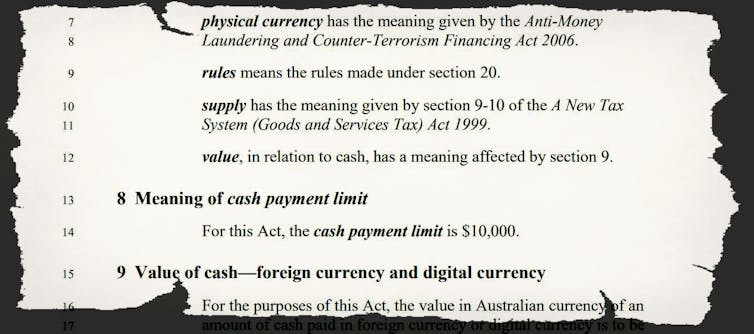

The proposed limit is A$10,000. Section 8 would make it an offence to make or accept cash payments of $10,000 occurring either as one-offs or in a linked sequence.

In parliament the minister said the $10,000 limit would not apply to person-to-person transactions, such as private sales of cars.

But these exceptions are not included in the the Bill. What is included is the phrase “specified by the rules”. Section 20 puts those rules in the minister’s hands. Future ministers may narrow exceptions and change rules.

It would remain legal to withdraw and hold more than $10,000. The stated intent of this Bill is to modify the use of cash, not the holding of cash.

All Australians will continue to be able to deposit and withdraw cash in excess of $10,000 into and from their accounts, and to store more than $10,000 of their money outside a bank.

Cash overboard

What’s proposed would limit competition (Visa, Mastercard, and PayPal would face a lesser competitor, for example) and limit long-held rights.

Everyday behaviour at present protected by the law would be criminalised.

In some cases, and perhaps many, the onus of proof would be reversed, with an “evidential burden” imposed on cash-using defendants.

As stunning is the assignment of “vicarious criminal liability” in Section 16.

Each partner in a partnership, each committee member of an incorporated association and each trustee of a trust or superannuation fund might become individually culpable for their entity’s use of cash.

Oddly, “bodies corporate and bodies politic” are treated differently (Part 3), and the government itself cannot be prosecuted, an uneven application of the law which has attracted little attention.

In my submission to the Senate inquiry (Submission 146) I argue the provisions would, among other things:

- undercut the ability of banks to head off a banking crisis by providing a trusted and useful form of money

- funnel more financial traffic through the equivalent of private toll roads

- remove a guaranteed and always available fallback from electronic transactions

- increase societal ill-ease and polarisation as citizens realise their rights have been eroded for not particularly compelling stated reasons.

Each point and many presented in other submissions need serious consideration, including in public Senate hearings.

The rationale presented

The speech to parliament introducing the bill was built around the hardly-new observation that cash payments can be “anonymous and untraceable”.

The government’s Black Economy Taskforce produced no detailed analysis but recommended the ban as a means of fighting tax avoidance, to:

make it more difficult to under-report income or charge lower prices and not remit good and services tax.

The speech also asserted that “more crucially” the ban would fight organised crime syndicates, although organised crime was not mentioned in the part of the taskforce report that dealt with the problem the limit was meant to address.

The guarantee dishonoured

Every pound note and then every dollar note issued by the Commonwealth Bank and then Reserve Bank of Australia bears this unconditional promise signed by the head of the bank and the head of the treasury:

This Australian note is legal tender throughout Australia and its territories.

The bank’s website suggests the promise is ongoing:

All previous issues of Australian banknotes retain their legal tender status.

Its note printing arm was mortified earlier this year at the apparently accidental omission of the last letter “i” from the word “responsibility” on the new more secure $50 note.

The Bill before the Senate contains many and much more serious errors.

Cash has been one of the few things we can absolutely rely on, whatever our status, situation or access to other payment means.

Removing (and dishonouring) that guarantee, while criminalising reliance on it, should not be done lightly in a mad rush to an arbitrary date.

Until now public debate about the proposal has been light, but concern is growing, even among quiet Australians.

Each Senator should ensure that last “i” in responsibility isn’t missing here either.

Author: Mark McGovern, Visiting Fellow, QUT Business School, Economics and Finance, Queensland University of Technology