Brilliant speech from Alex Brazier UK MPC member on macroprudential “How to: MACROPRU. 5 principles for macroprudential policy“.

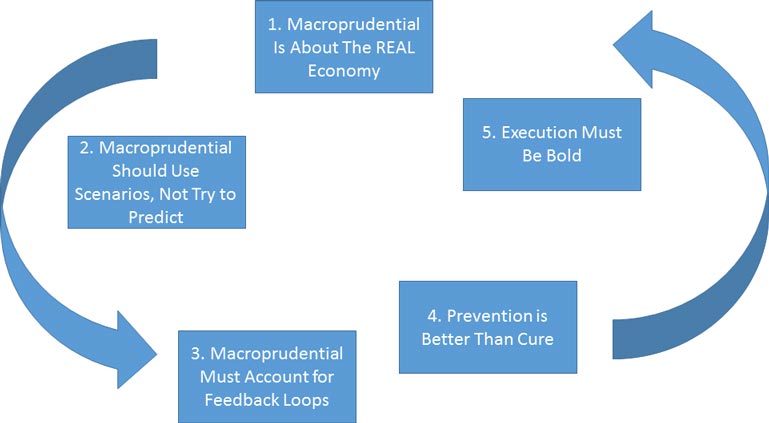

He argues that whilst macroprudential policy regimes are the child of the financial crisis and is now part of the framework of economic policy in the UK, if you ask ten economists what precisely macroprudential policy is, you’re likely to get ten different answers. He presents five guiding principles.

There are some highly relevant points here, which I believe the RBA and APRA must take on board. I summarise the main points in his speech, but I recommend reading the whole thing: This is genuinely important! In particular, note the limitation on relying on lifting bank capital alone.

There are some highly relevant points here, which I believe the RBA and APRA must take on board. I summarise the main points in his speech, but I recommend reading the whole thing: This is genuinely important! In particular, note the limitation on relying on lifting bank capital alone.

First, macroprudential policy may seem to be about regulating finance and the financial system but its ultimate objective the real economy. In a crisis, the financial system may be impacted by events in the economy – for example credit dries up, lenders are not matched with borrowers. Risks can no longer be shared. Companies and households must protect themselves. And in the limit, payments and transactions can’t take place. Economic activity grinds to a halt. These are the amplifiers that turn downturns into disasters; disasters that in the past have cost around 75% of GDP: £21,000 for every person in this country. So the job of macroprudential policy is to protect the real economy from the financial system, by protecting the financial system from the real economy. It is to ensure the system has the capacity to absorb bad economic news, so it doesn’t unduly amplify it.

Second, the calibration of macroprudential should address scenarios, not try to predict the future but look at “well, what if they do; how bad could it be?” In 2007, he says it was a failure to apply economics to the right question. There was too much reliance on recent historical precedent; on this time being different. And, even more dangerously, they relied on market measures of risk; indicators that often point to risks being at their lowest when risks are actually at their highest.

The re-focussing of economic research since the crisis has supported us in that. It has established, for example, how far: Recessions that follow credit booms are typically deeper and longer-lasting than others; Over-indebted borrowers contract aggregate demand as they deleverage; While they have high levels of debt, households are vulnerable to the unexpected. They cut back spending more sharply as incomes and house prices fall, amplifying any downturn; Distressed sales of homes drive house prices down; Reliance on foreign capital inflows can expose the economy to global risks; And credit booms overseas can translate to crises at home.

When all appears bright – as real estate prices rise, credit flows, foreign capital inflows increase, and the last thing on people’s minds is a downturn – our stress scenarios get tougher.

Third, feedback loops within the system mean that the entities in the system can be individually resilient, but still collectively overwhelmed by the stress scenario.

These are the feedback loops that helped to turn around $300 bn of subprime mortgage-related losses into well over $2.5 trillion of potential write-downs in the global banking sector within a year. Loops created by firesales of assets into illiquid markets, driving down market prices, forcing others to mark down the value of their holdings. This type of loop will be most aggressive when the fire-seller is funded through short-term debt. As asset prices fall, there is the threat of needing to repay that debt. But even financial companies that are completely safe in their own right, with little leverage, and making no promise that investors will get their money back, can contribute to these loops.

The rapid growth of open-ended investment funds, offering the opportunity to invest in less liquid securities but still to redeem the investment at short notice, has been a sea change in the financial system since the crisis. Assets under management in these funds now account for about 13% of global financial assets. It raises a question about whether end investors, under an ‘illusion of liquidity’ created by the offer of short-notice redemption, are holding more relatively illiquid assets. That matters. This investor behaviour en masse has the potential to create a feedback loop, with falling prices prompting redemptions, driving asset sales and further falls in prices.

And in a few cases, that loop can be reinforced by advantages to redeeming your investment first. Macroprudential policy must move – and is moving – beyond the core banking system.

Fourth, prevention is better than cure.

Having calibrated the economic stress and applied it to the system, it’s a question of building the necessary resilience into it. The results have been transformative. A system that could absorb losses of only 4% of (risk weighted) assets before the crisis now has equity of 13.5% and is on track to have overall loss absorbing capacity of around 28%. Our stress tests show that it could absorb a synchronised recession as deep as the financial crisis.

And if signals emerge that what could happen to the economy is getting worse, or the feedback loops in the system that would be set in motion are strengthening, we will go further.

But bank capital is not always the best tool to use to strengthen the system and is almost certainly not best used in isolation.

We have applied that principle in the mortgage market. Alongside capitalising banks to withstand a deep downturn in the housing market, we have put guards in place against looser lending standards: A limit on mortgage lending at high loan-to-income ratios; And a requirement to test that borrowers can still afford their loan repayments if interest rates rise.

These measures guard against lending standards that make the economy more risky; that make what could happen even worse. Debt overhangs – induced by looser lending standards – drag the economy down when corrected. And before they are, high levels of debt make consumer spending more susceptible to the unexpected. So they guard against lenders being exposed to both the direct risk of riskier individual loans, and the indirect risk of a more fragile economy. This multiplicity of effects means there is uncertainty about precisely how much bank capital would be needed to truly ensure bank resilience as underwriting standards loosen.

A diversified policy is also more comprehensive. It guards against regulatory arbitrage; of lending moving to foreign banks or non-bank parts of the financial system. And by reducing the risk of debt overhangs and high levels of debt, it makes the economy more stable too.

Fifth, It is that fortune favours the bold.

The Financial Policy Committee needs to match its judgements that what could happen has got worse with action to make the system more resilient. Why will that take boldness? Our actions will stop the financial system doing something it might otherwise have chosen to do in its own private interest – there will be opposition. The need to build resilience will often arise when private agents believe the risks are at their lowest. And if we are successful in ensuring the system is resilient, there will be no way of showing the benefits of our actions. We will appear to have been tilting at windmills.

As the memory of the financial crisis fades in the public conscience, making the case for our actions will get harder. Fortunately, we are bolstered by a statutory duty to act and powers to act with. And whether on building bank capital or establishing guards against looser lending standards, we have been willing to act. Just as building resilience takes guts, so too does allowing the strength we’ve put into the system to be drawn on when ‘what could happen’ threatens to become reality. Macroprudential policy must be fully countercyclical; not only tightening as risks build, but also loosening as downturn threatens. Without the confidence that we will do that, expectations of economic downturn will prompt the financial system to become risk averse; to hoard capital; to de-risk; to rein in. To create the very amplifying effects on the real economy we are trying to avoid.

A truly countercyclical approach means banks, for example, know their capital buffers can be depleted as they take impairments; Households can be confident that our rules won’t choke off the refinancing of their mortgage. And insurance companies know their solvency won’t be judged at prices in highly illiquid markets. We must be just as bold in loosening requirements when the economy turns down as we are in tightening them in the upswings. Boldness in the upswing to strengthen the system creates the space to be bold in the downturn and allow that strength to be tested and drawn on. Macroprudential fortune favours the bold.