APRA has released a paper on Loss-Absorbing Capacity of ADI’s.

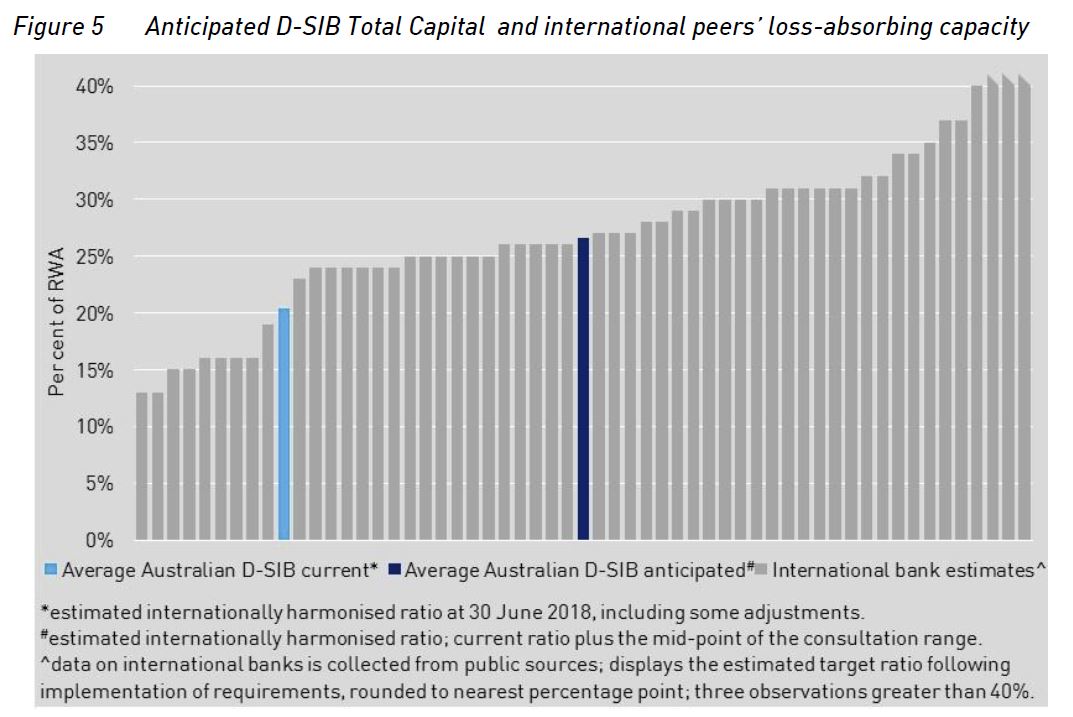

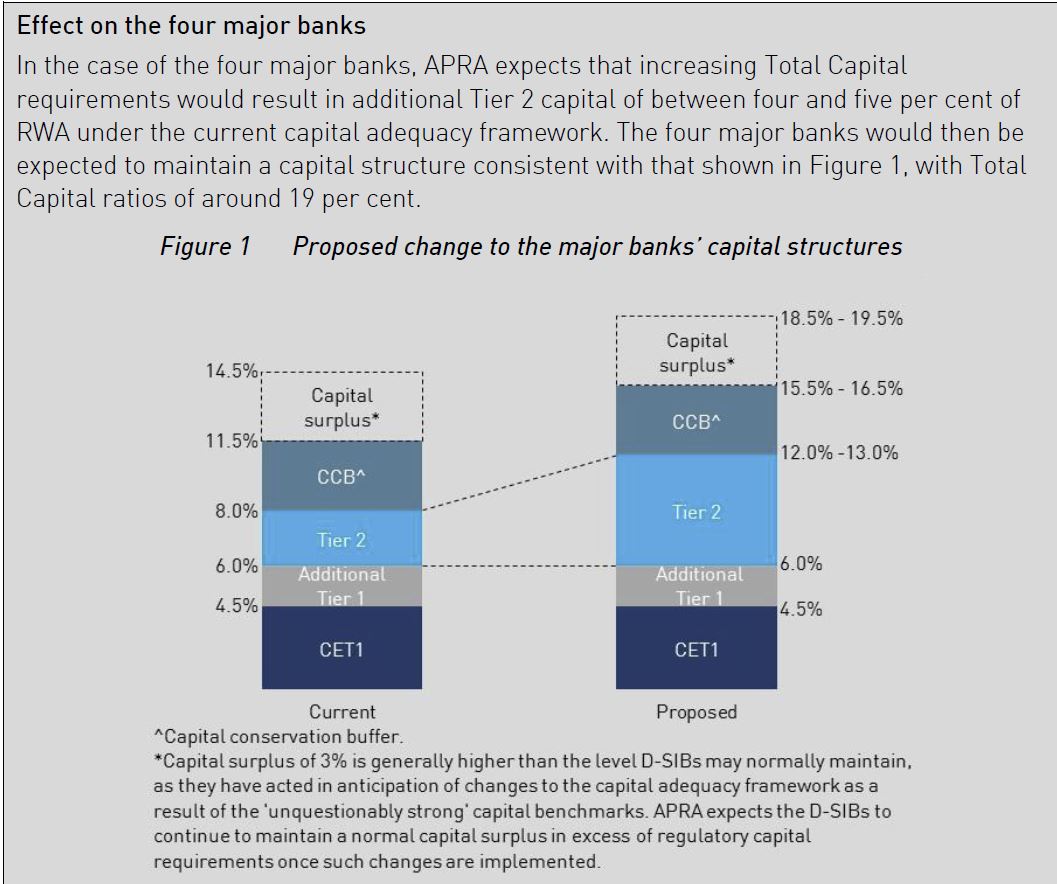

It shows that currently major Australian banks are at the lower end of Total Capital compared with international peers. As a result of proposed changes, major banks (Domestic systemically important banks in Australia, D-SIBs) will see their funding costs rise – incrementally over four years – by up to five basis points based on current pricing. This is intended to build in more financial resilience by lifting the capital requirements, centred on tier 2. Other banks may also be impacted to an extent.

If the D-SIBs were to maintain an additional four to five percentage points of Total Capital they would have ratios more in line with their international peers. But not in the top 25%, and the banks overseas are also lifting capital higher… so some tail chasing here! Is this “unquestionably strong”?

Under the proposals, each D-SIB would be required to maintain additional loss absorbency of between four and five percentage points of RWA. It is anticipated that each D-SIB’s Total Capital requirement would be adjusted by the same amount.

Under the proposals, each D-SIB would be required to maintain additional loss absorbency of between four and five percentage points of RWA. It is anticipated that each D-SIB’s Total Capital requirement would be adjusted by the same amount.

By way of background, the Australian Government’s 2014 Financial System Inquiry (FSI) recommended APRA implement a framework for loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity in line with emerging international practice, sufficient to facilitate the orderly resolution of Australian ADIs and minimise taxpayer support (FSI Rec 3). The Government supported this recommendation in its response to the FSI.

APRA’s role is not to eliminate failure altogether, but to reduce its probability and impact. This role is set out in APRA’s statutory objectives under the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 and the Banking Act 1959, which require APRA to protect depositors and pursue financial system stability. In performing its functions, APRA will balance those objectives with the need for efficiency, competition, contestability and competitive neutrality in the financial system.

Disorderly failures are inconsistent with APRA’s objectives, as they are highly disruptive to depositors and have an adverse impact on financial system stability. Australia has not experienced a disorderly ADI failure in recent history, though the failure of HIH Insurance Limited (HIH) in 2001 provides an example of the adverse consequences of a disorderly failure of an APRA-regulated institution. In that instance, policyholders were severely affected and essential insurance services to the broader community became unavailable for a period of time.

Conversely, orderly resolution of an ADI would occur when a problem is identified and escalated early enough to allow APRA and other financial regulators to manage and respond in a manner that protects the interests of depositors, stabilises the ADI’s critical functions and promotes financial stability. Achieving an orderly resolution does not necessarily mean a crisis is averted, rather the manner in which an ADI’s failure is managed would result in better outcomes given the circumstances.

APRA’s statutory powers were recently strengthened by the passage of the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018.

The effectiveness of resolution planning will be a focus for APRA over the coming years. APRA is in the process of developing a formalised framework for resolution planning and will consult further on this in 2019.

The proposals in this discussion paper focus on the availability of financial resources to support orderly resolution.

These proposals would ensure ADIs have adequate financial resources available to support orderly resolution in the highly unlikely event of failure. This will be achieved by adjusting, where appropriate, an ADI’s Total Capital requirement.

These proposals are distinct from APRA’s work on ensuring ADI capital levels are ‘unquestionably strong’, which relates to the ongoing resilience of institutions and is in response to a separate FSI recommendation (FSI Rec 1).

APRA is proposing an approach on loss-absorbing capacity that is simple, flexible and designed with the distinctive features of the Australian financial system in mind, and has been developed in collaboration with the other members of the Council of Financial Regulators. The key features of the proposals include:

- for the four major banks – increasing Total Capital requirements by four to five percentage points of risk-weighted assets

- for other ADIs – likely no adjustment, although a small number may be required to maintain additional Total Capital depending on the outcome of resolution planning, which would inform the appropriate amount of additional loss absorbency required to achieve orderly resolution. This assessment would occur on an institution-by-institution basis.

Tier 2 capital instruments are designed to convert to ordinary shares or be written off at the point of non-viability, which means they will be available to absorb losses and can be used to facilitate resolution actions. Tier 2 capital instruments have been a feature of ADI capital structures in various forms since being introduced as part of the 1988 Basel Accord. These instruments have been used as part of resolution actions in other jurisdictions, supporting orderly outcomes.

It is also important that holders of instruments which are intended to be converted or written off in resolution understand the distinctive risks of these investments. In the context of AT1 instruments, APRA has noted that it is inadvisable for investors to view such instruments as higher-yielding fixed-interest investments, without understanding the loss-absorbing role they play in a resolution.15 In the case of the Australian ADIs’ Tier 2 capital instruments, these are mostly issued to institutional investors, who are likely to understand the risks involved.

As ADIs will be able to use any form of capital to meet increased Total Capital requirements, APRA anticipates the bulk of additional capital raised will be in the form of Tier 2 capital. The proposed changes are expected to marginally increase each major bank’s cost of funding – incrementally over four years – by up to five basis points based on current pricing. This is not expected to have an immediate or material effect on lending rates.

APRA proposes that the increased requirements will take full effect from 2023, following relevant ADIs being notified of adjustments to Total Capital requirements from 2019.

In addition to the proposals outlined in this discussion paper, APRA intends to consult on a framework for recovery and resolution in 2019, which will include further details on resolution planning.

APRA Chairman Wayne Byres said one of APRA’s core functions as Australia’s prudential regulator is to plan for, and if required, execute the orderly resolution of the financial institutions it regulates.

“The resilience of the Australian banking system continues to improve, underpinned by the build-up of capital over the last decade.

“However, no matter how resilient financial institutions are, the possibility of failure cannot be entirely removed. Therefore, in addition to strengthening the resilience of the financial system, it is prudent to plan for the unlikely event of failure.

“The events of the global financial crisis demonstrated the impact that failures can have on the broader financial system and the subsequent social and economic consequences.

“The aim of these proposals and resolution planning more broadly is to ensure that the failure of a financial institutions can be resolved in an orderly fashion, which protects the interests of beneficiaries and minimises disruption to the financial system,” Mr Byres said.

Written submissions are open to 8 February 2019.

Note this footnote.

“Other jurisdictions have developed frameworks that include, for example, the creation of additional types of contractual instruments or a statutory bail-in power. The Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018 did not contain, and APRA does not have, a statutory power to write-off or convert the interests of other creditors, including depositors of a failing ADI, whether in, or leading up to, resolution (often referred to as a bail-in power)”

Does this address the bail-in concerns you have raised?

Thanks, but no, given the FSB and G20 directives and NZ example. Whats the source of that footnote?

not Sure what you mean by the “source”? APRA is saying they don’t have the power you claim they do. NZ example is very different as the RBNZ explicitly do have the power via their Open Bank Resolution regime. APRA say they recognise the statutory powers used in other regimes but have opted not to pursue that path

If there was no intent re deposits, then to be clear, Parliament should have passed the amendment to the Bill making this clear… they did not… hence the vagueness…

Do you agree that deposits are insulated from loss by their seniority in the capital stack? So that losses are only possible if the CET1, AT1, T2 and senior unsecured are first wiped out?

Yes, the “stack” would be eaten from the top as it were, but remember this is NOT in a gone concern, its is a rescue scenario, so not sure the logic is as clear – could argue that by using deposits, you are saving depositors… you would still want to keep share capital in the bank, or convert deposits to equity to secure the financial structure. Suspect the vagueness is to maximise the wriggle room…