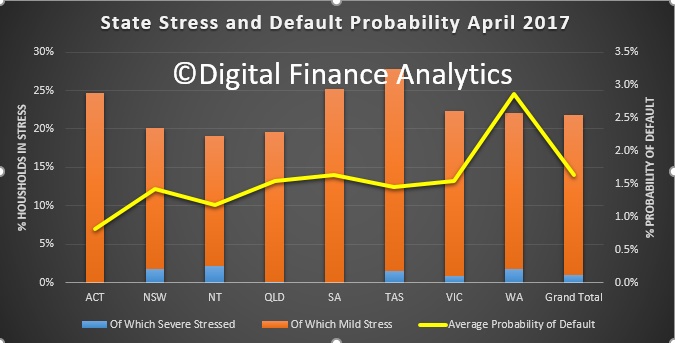

The Australian Financial Review covered the latest DFA mortgage stress research today, even if they managed to scramble the data in the chart I provided. Here is the correct data.

Household debt is rocketing towards 190 per cent of disposable incomes, ramping up pressure on the Reserve Bank of Australia and regulators to take action that avoids a US-style debt crisis.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull endorsed Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe’s warning that household debt is rising too fast and linked the high burden of servicing loans to the need for the Commonwealth to manage its debt.

A key reason for maintaining the government’s AAA credit rating is that credit agencies assume Canberra will bail out any banks that are blind-sided by a housing crisis.

“All of the warnings that the Reserve Bank and APRA have made about rising levels of debt are well made,” Mr Turnbull said in Sydney on Wednesday. “That’s their job, the system is working. They’re making changes and adjustments to the prudential rules that will take some of the heat out of the market, just at the right time.”

State household debt stress and default probability, Apr 2017

Galloping house prices in Sydney and Melbourne, as well as a surge in interest-only loans, have forced regulators into taking rearguard action against the potential financial risks that may unfold if the debt load becomes too heavy for households to bear.

A weak labour market and sluggish wages growth means the Reserve Bank is unable to raise the official cash rate to curb property market excesses for fear of crushing consumer spending, which accounts for the equivalent of about 60 per cent of the economy.

Figures published by the bank on Wednesday show the household-debt-to-disposable-income ratio is now sitting at about 189 per cent. The figure has accelerated in recent years after holding steady for much of the 2000s at about 160 per cent. A quarter-century ago the measure stood at about 60 per cent.

Research by consultants Digital Finance Analytics shows that of the nation’s 3.1 million households about 670,000 are unable to cover their living and interest rate costs, despite borrowing costs at historically modest levels.

The figures also challenge the Reserve Bank’s view that much of the debt is secure because it sits with high-income households, rather than the traditional “battler”.

Not the usual suspects

“The battlers are always close to the edge, but if you look at those in severe stress they’re more widely spread,” said Martin North, the firm’s principal.

“It’s the more affluent household groups, with big mortgages and lifestyle, now finding mortgage rates are rising when wages aren’t that are more exposed. They’re used to being profligate and they may not have as much in the bank as you’d expect.

“Not every affluent household is in difficulty, but it’s enough to make it interesting.”

Many heavily hocked households are increasingly facing a multi-directional squeeze with wages growth faltering just as many banks have already increased their mortgage rates by about 25 basis points in recent months. At the same time, costs bourne by many in the middle class are rising – for energy, school fees, childcare, medical and other expenses.

Even if the Reserve Bank does nothing, borrowing costs are almost certain to continue rising as banks are required by regulators to put more capital aside.

Impact would be severe

“We’ve brought forward all the housing consumption we can – that’s reflected in debt,” said IFM Investors chief economist Alex Joiner. “And that debt has accumulated rapidly, ahead of incomes.”

Credit growth continues to expand at about 6 per cent a year, while wages growth is less than 2 per cent, and household incomes are running at 3 per cent.

Unlike many other advanced economies that hit the wall after the 2008 global financial crisis, Australian households have never experienced a period of active de-leveraging, in which credit contracts at an annual rate.

Mr Joiner warns that the debt load means the Reserve Bank now has one of the world’s most “asymmetrical” monetary policy settings – in which even the smallest increase in the official cash rate will cascade heavily onto household cash flows.

“It’s come to a point where you think policy has been exhausted,” he said. “The Reserve Bank have been the stewards of the economy for too long and every time there’s been a setback we rely on monetary policy to fix it.

“I don’t think we can rely on that going forward.”

State household debt stress and default probability, Apr 2017

State household debt stress and default probability, Apr 2017