Speaking to the Conservative Party conference in September 2017, the UK prime minister, Theresa May, gave a stark assessment of the UK housing market which made for depressing listening for many young people: “For many the chance of getting onto the housing ladder has become a distant dream”, she said.

Now a new report by the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) provides further, clear evidence of this. The study finds that home ownership among 25 to 34-year-olds has declined sharply over the past 20 years. Home ownership rates have declined from 43% at age 27 for someone born in the late 1970s, to just 25% for someone aged 27 who was born in the late 1980s.

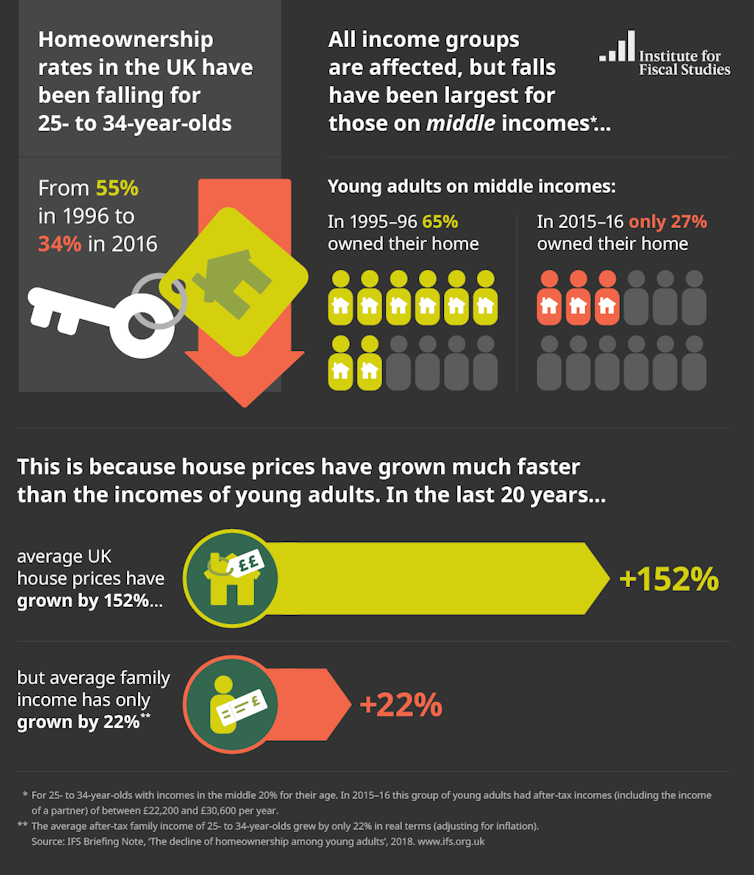

The most significant decline has been for middle-income young people, whose rate of home ownership has fallen from 65% in 1995/6 to 27% now – most significantly hitting aspirant buyers in London and the South-East.

Causes and consequences

The IFS study lays the blame for all this on the growing gap between house prices and incomes. Adjusting for inflation, house prices have risen 150% in the 20 years to 2015/16, while real incomes for 25 to 34-year-olds have grown by 22% (and almost all of that growth happened before the 2008 crash).

A bleak picture. Institute for Fiscal Studies.

But, as the report acknowledges, the problem goes much deeper than this. Home ownership rates differ by region. Although there has been a decline in home ownership rates for young people across all areas of Great Britain, the decline is less significant in the North East and Cumbria as well as in Scotland and the South West. The biggest decline in ownership has been in the South-East, the North-West (excluding Cumbria) and London.

So a person aged 25 to 34 is more than twice as likely to own their own home in Cumbria, as their counterpart in London. Worse, young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to own their own homes – even after controlling for differences in education and earnings. Home ownership continues to reflect a deeper inequality of opportunity in our society.

More houses needed

Part of the problem is that both Labour and Conservative governments have seen housing as a single, stand-alone market and have focused their attention on what is happening to prices in London. But housing is a number of different markets, which have regional variations and different interactions between the owner-occupier, private rented and social rented sectors.

Regional variations in house prices for similar sized properties reflect the imbalances of the economy: it is heavily reliant on financial services, which are concentrated in London, while the public sector makes up a significant share of many local economies – particularly in the North. Migration from across the UK to overcrowded and expensive areas – such as London and the South-East – have put property prices in those areas even further out of reach for would-be buyers.

To make matters worse, both Labour and Conservative governments have routinely failed to build enough houses. While the current government’s aim to build 300,000 new properties a year by 2020 is welcome, it is simply not enough to meet the backlog in demand – let alone address the fundamental affordability problem.

Where homes are being built, they’re often the wrong types of homes, in the wrong places. Family homes are being built, despite there being some four million under-occupied such properties across the country.

Not that long ago, government was reducing the housing stock in many parts of the North, through the disastrous Housing Market Renewal programme. Houses are currently being sold in smaller cities such as Liverpool and Stoke-on-Trent for just £1. And none of the government’s actions suggest that ministers understand these issues, or are prepared to address them.

House price inflation – and the awful affect it is having on home ownership rates for young people – is part of a wider problem of the global asset bubble. This bubble has seen huge increases in the price of assets – stocks, housing, bonds – in high income countries such as the UK. Successive governments have helped to fuel this through quantitative easing, ultra-cheap money and successive raids on pension funds.

What’s needed to address this asset bubble is a substantive increase in interest rates. But while this may slow the growth in house prices, the sad truth is it will do nothing to make housing more affordable for most young people.

Author: Chris O’Leary, Deputy Director, Policy Evaluation and Research Unit and Senior Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University