Via Moody’s. On 21 May, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) announced a proposal to remove its requirement that banks use an interest rate floor of at least 7% in their assessment of mortgage serviceability. The proposal will help support credit growth and could stem falling house prices. The announcement also has the potential to increase household leverage. However, banks have progressively tightened mortgage underwriting practices, which will mitigate the risk of a resurgence in excessive credit growth and another house price boom.

Since December 2014, APRA has required banks to assess loan serviceability using the higher of either an interest rate floor of at least 7% or a 2% cent buffer over the loan’s interest rate. APRA also recommended that banks should operate above these minimum requirements, which resulted in most banks using a 7.25% floor and 2.25% buffer. Under APRA’s proposal, banks will be allowed to set their own interest rate floor, but will need to incorporate a buffer of at least 2.5%.

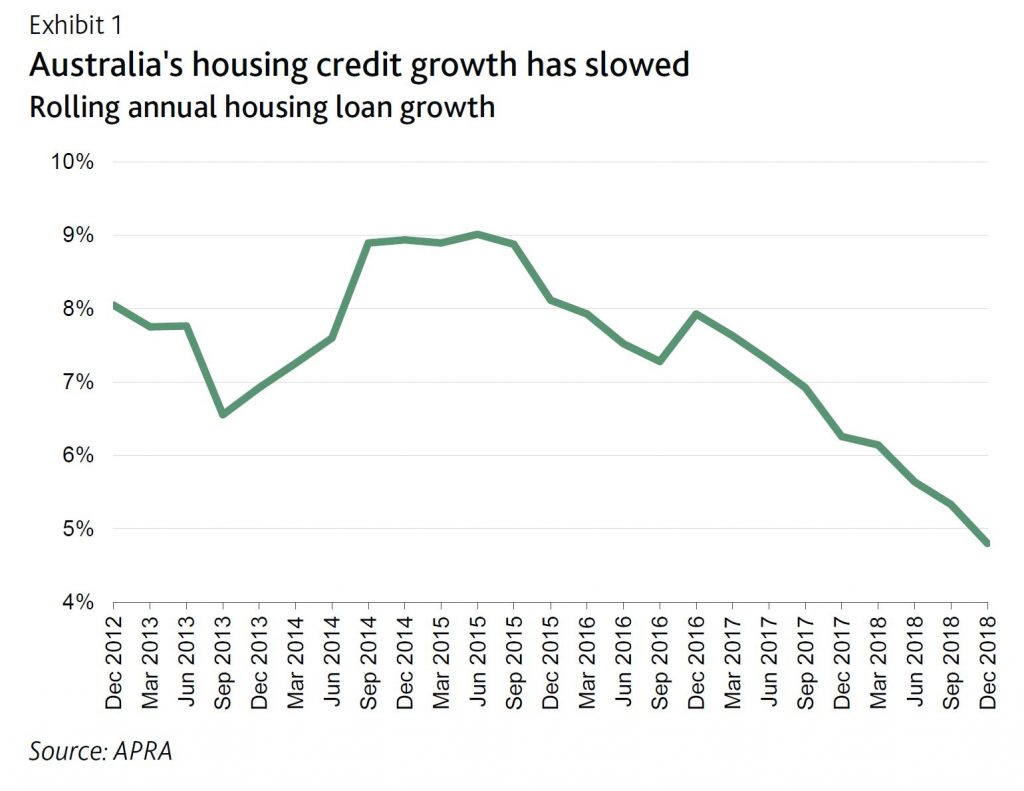

The proposal is likely to increase borrowing capacity, with some banks reporting that the interest rate floor has been a key contributor to the decline in borrowing capacity in recent years1. Improving access to credit will support credit growth for the banks, which has declined significantly from its peak in 2014 …

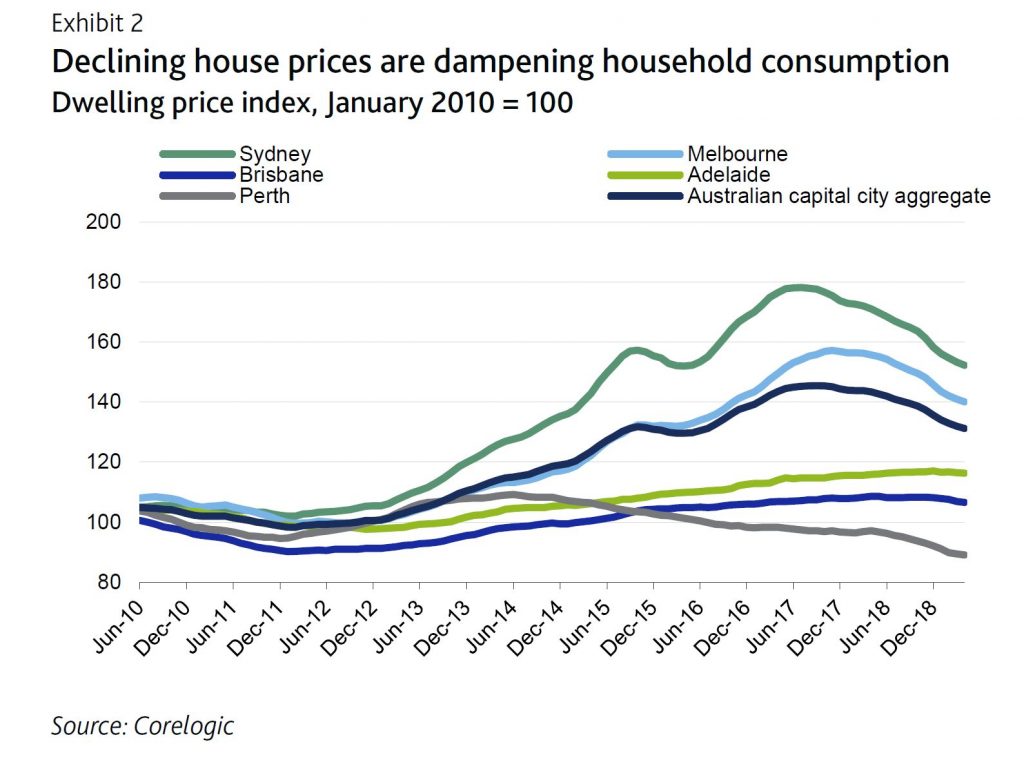

… and, in turn, stem the fall in house prices.

Falling house prices are dampening household consumption and contributing to a weaker growth outlook for Australia.

APRA said that a review of the interest rate floor was necessary because interest rates have declined since 2014 and are likely to remain at historically low levels for some time, which means that the gap between the 7% floor and actual rates paid on home loans may become unnecessarily wide. Furthermore, since the introduction of a single rate floor, banks have introduced differentiated pricing for mortgage products. This has resulted in the highest interest-rate buffer being applied on lower-priced and less-risky owner-occupier principle and interest loans, while the smallest buffer was being applied to investors with interest-only loans. Interest-only loans are generally more risky and attract a higher interest rate.

This proposal reflects the unwinding of APRA’s macroprucential policies that were progressively introduced from 2014, during a period of rapid growth in credit and housing prices. Such policies included interest-only lending restrictions that were removed in December 2018 and the removal of investor lending restrictions in April 2018. These restrictions had been in place since March 2017 and December 2014, respectively.

Despite declining house prices, high household leverage remains a key risk to Australian banks. And there is a risk that the lowering of the interest rate floor, in combination with the potential for the Reserve Bank of Australia to lower the cash rate later this year, could drive a resurgence in excessive credit growth and another house-price boom. However, banks have progressively tightened mortgage underwriting practices, which provides a strong mitigant to this risk. For example, banks have become increasingly focussed on the verification of a customer’s declared income and living expenses. This move has decreased borrower capacity and significantly

lengthened the mortgage application process. Banks have also developed limits on lending at high debt/income levels, where debt is greater than 6x a borrower’s income, and have introduced haircuts on uncertain and variable income, such as non-salary and rental income.