Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North discuss the amazing display of “strength” by Central Bankers, and why it will end in tears.

It gives us no pleasure to be proved right!

"Intelligent Insight"

Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North discuss the amazing display of “strength” by Central Bankers, and why it will end in tears.

It gives us no pleasure to be proved right!

Welcome to our latest post covering finance and property news with a distinctively Australian flavour. Given the current market gyrations, we are going to examine the latest critical data each day, because a week is a long time in politics but a lifetime on the markets at the moment…

March Live Q&A:

As Australia’s financial system adjusts to the coronavirus (COVID-19), financial regulators and the Australian Government are working closely together to help ensure that Australia’s financial markets continue to operate effectively and that credit is available to households and businesses. (Refer to earlier Council of Financial Regulators’ (CFR) press release.) Australia’s financial system is resilient and it is well placed to deal with the effects of the coronavirus. At the same time, trading liquidity has deteriorated in some markets.

In response, the Reserve Bank stands ready to purchase Australian government bonds in the secondary market to support the smooth functioning of that market, which is a key pricing benchmark for the Australian financial system. The Bank will also be conducting one-month and three-month repo operations in its daily market operations until further notice to provide liquidity to Australian financial markets. In addition the Bank will conduct longer term repo operations of six-months maturity or longer at least weekly, as long as market conditions warrant. The Reserve Bank and the AOFM are in close liaison in monitoring market conditions and supporting continued functioning of the market.

The Bank will announce further policy measures to support the Australian economy on Thursday.

DFA is expecting a 0.25% rate cut, and formal QE to go alongside the repo operations already in train.

Understand that the Fed’s actions (and other central banks actually) are NOT about supporting stock prices – as they are determined more by prospective future cash flows from business operations than anything else. There is a lot of rubbish in the media on this point.

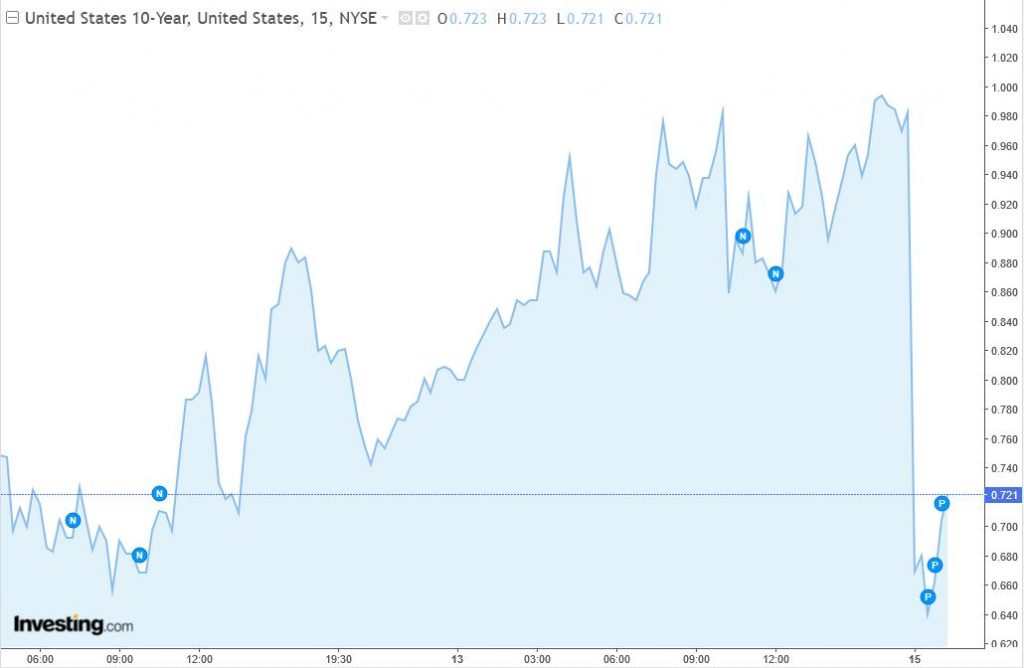

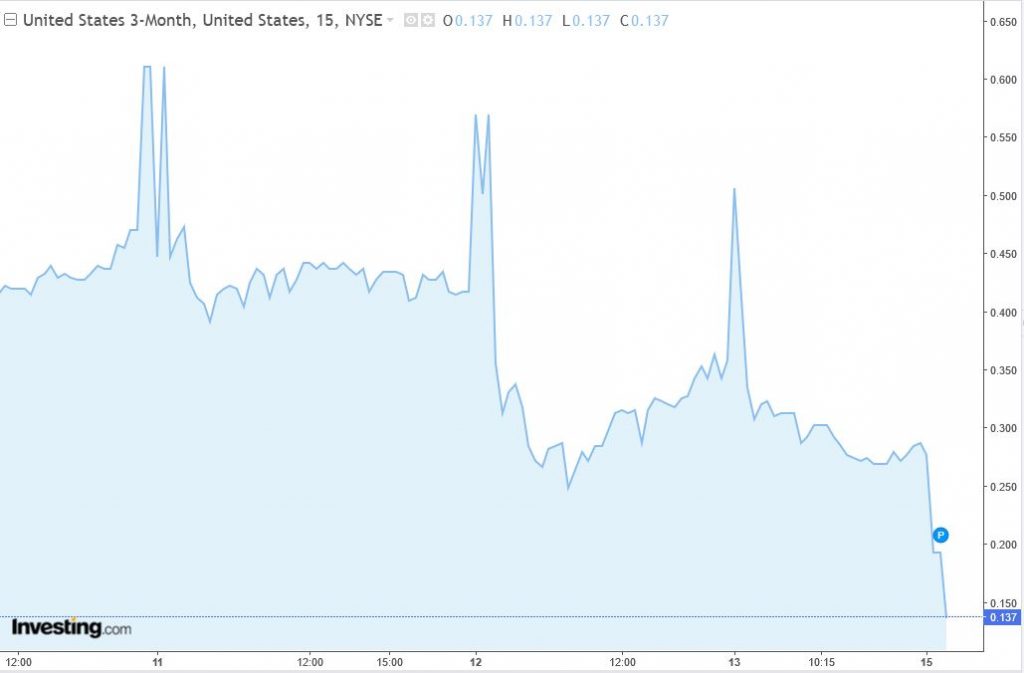

But bond rates are another matter. Given the hike in bond rates we saw last week – which translates to higher interest bills, and funding issues, the T10 and 3 Month US rates dropped after the announcement. T10 was down 24%

The 3 month dropped 50%.

Question is, will this be enough – we think not. Watch for more action to try to control rates.

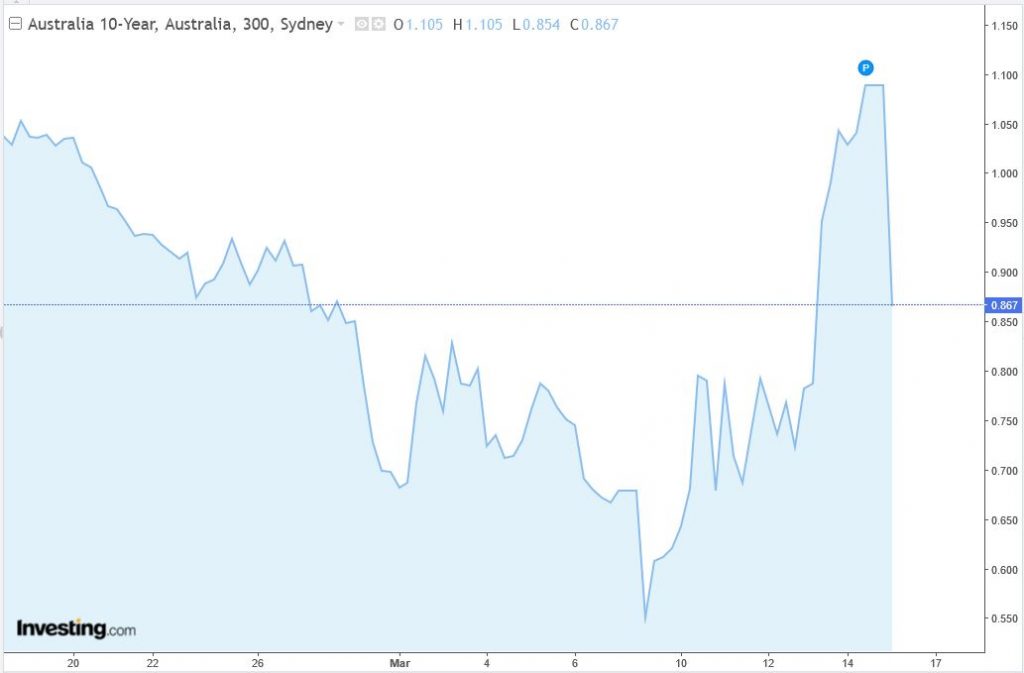

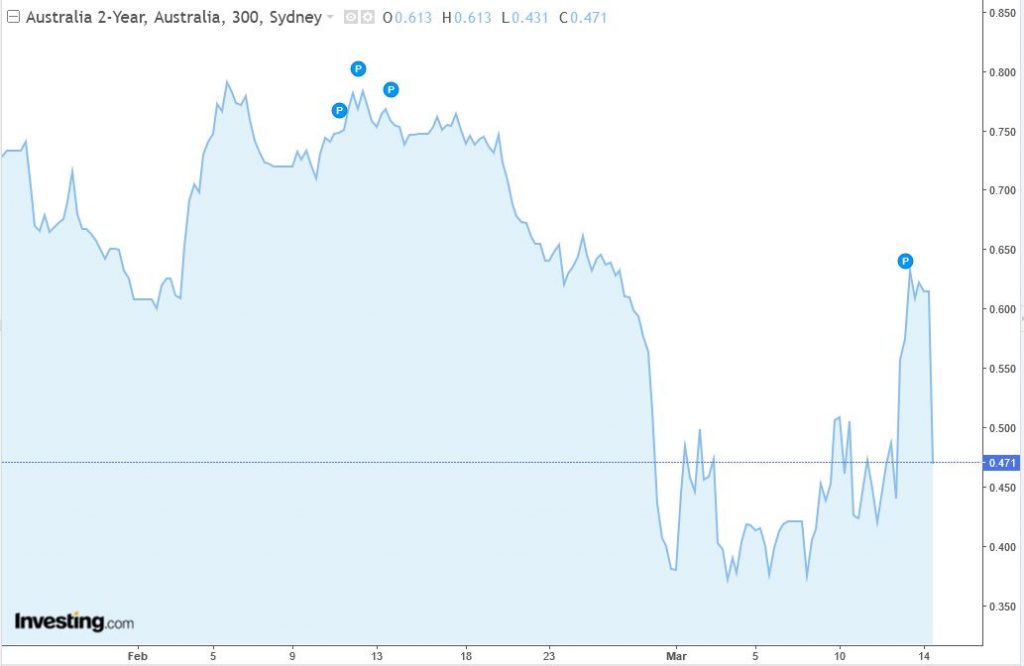

Aussie bonds also came down, with the 10 year down 13% and the 2 year down 20%.

Chair Jerome Powell’s announcement this morning has spooked the US markets, with the futures price falling 5% and activating a trading halt.

The raft of announcements, which we have already covered has scared the markets, and it suggest a weak opening in the US later.

There are severe cracks opening up in the financial system, with treasury pricing haywire, the Feds initial massive repo sale under-subscribed, and direct liquidity support ineffective. Of course they want to shore up the financial markets, and he was at pains in the press conference (telephone) to underscore how well capitalised the banks are, and that negative rates are not coming.

Worth also noting the FED slashed the Interest on Excess Reserves that it pays the banks for parking their cash at the Fed to 0.10% effective Monday. Back in the heady days of 2019, the Fed paid the banks $34 billion in interest on reserves. This income just went away.

US Bank shares are under pressure. Here in Australia the Financials Sector Index is down around 4%, but rising from opening lows.

The market was 4% lower on opening today, despite the various actions from central banks and other regulatory agencies. We will see how things develop later as other markets open.

Jerome Powell Fed chair has been underscoring the resilience of the financial systems and the power of the tools available, though said the under-subscribed repo strategy they executed last week showed they needed to purchase securities direct but given the market reaction, they then needed to act aggressively to support liquidity beyond that. Hence the rate cut decision.

As Australia’s financial system adjusts to the coronavirus (COVID-19), financial regulators and the Australian Government are working closely together to help ensure that Australia’s financial markets continue to operate effectively and that credit is available to households and businesses.

Australia’s financial system is resilient and it is well placed to deal with the effects of COVID-19. The banking system is well capitalised and is in a strong liquidity position. Substantial financial buffers are available to be drawn down if required to support the economy.

The funding position of the banking system is strong. Australia’s financial institutions, market participants and market infrastructure providers have undertaken substantial investments in their operational capability to deal with the effects of the virus. At the same time, trading liquidity has deteriorated in some markets and financial institutions are having to adjust to a more volatile environment. The financial regulators are in regular contact with financial institutions, market participants and market infrastructure providers.

The RBA is continuing to support the liquidity of the system. As part of this support it will be conducting one-month and three-month repurchase (repo) operations until further notice. In addition it will conduct repo operations of six-months maturity or longer at least weekly, as long as market conditions warrant. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is ensuring banking institutions pre-position themselves to take advantage of the RBA’s supportive measures.

Given the disruption being caused by COVID-19, Council members are examining how the timing of regulatory initiatives might be adjusted to allow financial institutions to concentrate on their businesses and assist their customers.

APRA and ASIC acknowledge the importance of the continued flow of credit to affected customers and industries in the current environment. Banks and other lenders are therefore encouraged to work constructively with affected customers during any period of disruption. For their part, APRA and ASIC will take account of the circumstances in which lenders, acting reasonably, are currently operating during the prevailing circumstances when administering their respective laws and regulations. Both agencies also stand ready to deal with problems firms may encounter in complying with the law due to the impact of COVID-19 through a facilitative and constructive approach. In particular, each agency will, where warranted, provide relief or waivers from regulatory requirements. This includes requirements on listed companies associated with secondary capital raisings, annual general meetings and audits. ASIC will also work with financial institutions to further accelerate the payment of outstanding remediation to customers as soon as possible.

The Council is meeting with major lenders later this week to discuss how they can best support households and businesses through this challenging period. The Council will be emphasising the importance of a continuing supply of credit, particularly to small businesses. It will be also discussing with the lenders whether there are impediments to lending that Council members could help to address.

The members of the Council of Financial Regulators remain in close contact with one another and with the Australian Government and their international peers. The Council will have its regular quarterly meeting on Friday 20 March at which the impact of COVID-19 on the financial system will be further discussed. The Council and the Australian Treasurer are also holding teleconferences at least weekly.

Council of Financial Regulators

The Council of Financial Regulators (the Council) is the coordinating body for Australia’s main financial regulatory agencies. There are four members: the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Treasury and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). The Reserve Bank Governor chairs the Council and the RBA provides secretariat support. It is a non-statutory body, without regulatory or policy decision-making powers. Those powers reside with its members. The Council’s objectives are to promote stability of the Australian financial system and support effective and efficient regulation by Australia’s financial regulatory agencies. In doing so, the Council recognises the benefits of a competitive, efficient and fair financial system. The Council operates as a forum for cooperation and coordination among member agencies. It meets each quarter, or more often if required.

Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, State Street, and Wells Fargo, in a statement via the Financial Services Forum, agreed to temporarily suspend share buybacks for the remainder of 1Q and through 2Q 2020.

“The decision on buybacks is consistent with our collective objective to use our significant capital and liquidity to provide maximum support to individuals, small businesses, and the broader economy through lending and other important services,” the group wrote, citing the COVID-19 pandemic as an “unprecedented challenge”

As part of the Australian Government’s response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), ASIC has taken steps to ensure Australian equity markets remain resilient.

Australian equity markets have seen record trading volumes in the last two weeks. ASIC, along with the other Council of Financial Regulators agencies, have been closely monitoring financial markets to ensure they remain fair and orderly. Australian markets have been strong and resilient over this period, and this action is pre-emptive and intended to maintain those high standards.

In addition to increasing volumes, Australia’s equity markets have seen exponential increases in the number of trades executed, with a particularly large increase in trades last Friday, 13 March. While there was no disruption to market operations on Friday, there was a significant backlog of work required to be undertaken over the weekend by the exchanges and trading participants. If the number of trades executed continues to increase, it will put strain on the processing and risk management capabilities of market infrastructure and market participants.

Accordingly, ASIC has issued directions under the ASIC Market Integrity Rules to a number of large equity market participants, requiring those participants to limit the number of trades executed each day until further notice. These directions require those firms to reduce their number of executed trades by up to 25% from the levels executed on Friday. This action will require high volume participants and their clients to actively manage their volumes. We do not expect these limits to impact the ability of retail consumers to execute trades.

ASIC will continue to closely monitor market conditions and take action where needed to ensure markets remain fair and orderly.

The Fed has just cut rates to 0- 1/4 percent.

In addition the Federal Reserve on Sunday announced it would purchases $700 billion in bonds and securities to stabilize financial markets and support the economy.

The emergency rate cut and push to flood the Treasury bond market with liquidity comes as the coronavirus pandemic forces businesses across the U.S. and world to shutter, likely plunging the global economy into a recession.

This is part of a coordinated global response, the Fed says.

The Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Swiss National Bank are today announcing a coordinated action to enhance the provision of liquidity via the standing U.S. dollar liquidity swap line arrangements.

These central banks have agreed to lower the pricing on the standing U.S. dollar liquidity swap arrangements by 25 basis points, so that the new rate will be the U.S. dollar overnight index swap (OIS) rate plus 25 basis points. To increase the swap lines’ effectiveness in providing term liquidity, the foreign central banks with regular U.S. dollar liquidity operations have also agreed to begin offering U.S. dollars weekly in each jurisdiction with an 84-day maturity, in addition to the 1-week maturity operations currently offered. These changes will take effect with the next scheduled operations during the week of March 16.1 The new pricing and maturity offerings will remain in place as long as appropriate to support the smooth functioning of U.S. dollar funding markets.

The swap lines are available standing facilities and serve as an important liquidity backstop to ease strains in global funding markets, thereby helping to mitigate the effects of such strains on the supply of credit to households and businesses, both domestically and abroad.

The coronavirus outbreak has harmed communities and disrupted economic activity in many countries, including the United States. Global financial conditions have also been significantly affected. Available economic data show that the U.S. economy came into this challenging period on a strong footing. Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in January indicates that the labor market remained strong through February and economic activity rose at a moderate rate. Job gains have been solid, on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Although household spending rose at a moderate pace, business fixed investment and exports remained weak. More recently, the energy sector has come under stress. On a 12‑month basis, overall inflation and inflation for items other than food and energy are running below 2 percent. Market-based measures of inflation compensation have declined; survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The effects of the coronavirus will weigh on economic activity in the near term and pose risks to the economic outlook. In light of these developments, the Committee decided to lower the target range for the federal funds rate to 0 to 1/4 percent. The Committee expects to maintain this target range until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events and is on track to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals. This action will help support economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation returning to the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective.

The Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook, including information related to public health, as well as global developments and muted inflation pressures, and will use its tools and act as appropriate to support the economy. In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the stance of monetary policy, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its maximum employment objective and its symmetric 2 percent inflation objective. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments.

The Federal Reserve is prepared to use its full range of tools to support the flow of credit to households and businesses and thereby promote its maximum employment and price stability goals. To support the smooth functioning of markets for Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities that are central to the flow of credit to households and businesses, over coming months the Committee will increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $500 billion and its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $200 billion. The Committee will also reinvest all principal payments from the Federal Reserve’s holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities. In addition, the Open Market Desk has recently expanded its overnight and term repurchase agreement operations. The Committee will continue to closely monitor market conditions and is prepared to adjust its plans as appropriate.

Voting for the monetary policy action were Jerome H. Powell, Chair; John C. Williams, Vice Chair; Michelle W. Bowman; Lael Brainard; Richard H. Clarida; Patrick Harker; Robert S. Kaplan; Neel Kashkari; and Randal K. Quarles. Voting against this action was Loretta J. Mester, who was fully supportive of all of the actions taken to promote the smooth functioning of markets and the flow of credit to households and businesses but preferred to reduce the target range for the federal funds rate to 1/2 to 3/4 percent at this meeting.

In a related set of actions to support the credit needs of households and businesses, the Federal Reserve announced measures related to the discount window, intraday credit, bank capital and liquidity buffers, reserve requirements, and—in coordination with other central banks—the U.S. dollar liquidity swap line arrangements. More information can be found on the Federal Reserve Board’s website.