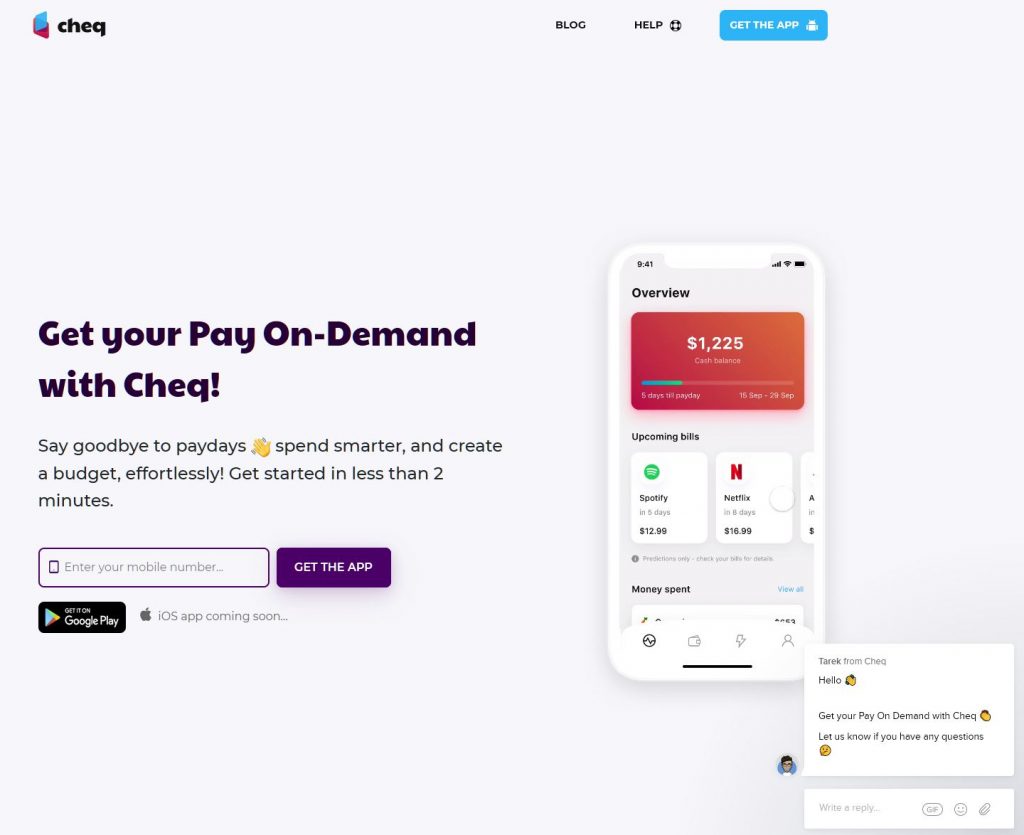

In the latest of our “Fintech Spotlight” series of posts, we look at a new player who is attempting to disrupt Payday lending using a digital platform and smart analytics. As normal, DFA was not paid for this post, and the views expressed are our own.

I caught up with CEO & Co-Founder of Fintech Cheq, Tarek Ayoub, to discuss how Cheq has the potential to prevent thousands of vulnerable Australians from turning to predatory payday lenders, with their sky-high interest rates and fees, and their vicious repayment structures which are designed to keep people trapped in a crippling cycle of debt.

In fact, Cheq has just raised $1.75 million in debt and equity to launch a revolutionary ‘Pay On-Demand’ (POD) solution. This allows working Australians facing a cash shortfall to access their accrued wages instantly up to $200. Cheq charges a fixed transaction fee of 5 percent with absolutely no additional fees or interest, compared to the 52 to 1,000 per cent annualized percentage rates charged by payday lenders on similar amounts.

We know there are around 5.9 million Australians currently living paycheck to paycheck who often resort to payday lenders during cash shortfalls.

Ayoub, an ex-management consultant, with a track record in the finance sector, highlights the rise of the ‘on-demand’ economy. “As our society increasingly embraces the ‘on-demand’ model of consumption, it is only natural that we begin to see this flow over into remuneration. You can get food, TV shows, cleaning services, dog walking, and everything in between on demand. So why is it that we can’t yet access our own money – money we have already physically worked for – as soon as it’s needed?”

Cheq is available via a mobile app, were individuals can register for the service and link their bank account. Cheq uses the transactional data from that account to analyse and profile the spending habits of the individual, using machine learning, AI, and statistical analysis.

As important as the access to cash – up to $200 is, the real power of Cheq is the personal financial management solutions built into the app which helps users by predicting upcoming bills, categorising expenses, and creating budgets for better money management.

As the relationship builds, Cheq is able to offer suggestions to help manage financial stress. And the $200 advance, ahead of the next wage, is automatically repaid in one hit, or as stage payments repaid in 2, 3 or 4 wage cycles (which can be weekly, fortnightly or monthly). Money is only recouped from a user’s bank account once wages are received, so they can’t exceed their spending capacity or get trapped in debt.

The $1.75m comprised $1.4m equity and a $350k debt facility from investors including VFS Group (an early investor in Grow Super) and Released Ventures. Interest has been received for more funding as the firm has grown to 5 employees and with ambitious plans ahead.

Six hundred users downloaded Cheq from the app store within 2 days of its beta launch and had more than ten thousand downloads in the first month. The typical user of the service is aged 24-35 years, often working in retail, call centres or fast food sectors. 70% of users have also used “Buy Now Pay Later” (BNPL) apps and 60% had also used payday loans. Most funds were used for transport and groceries, though many users left the money untouched in their accounts. But the most fascinating aspect is the fact that Cheq users were often weaned off payday loans in just a few months. This could be a game-changer.

Cheq is quite selective in their customer assessment, with 4,000 rejected so far. Applicants are screened via their proprietary assessment model, without relying on external credit scores or other financial data such as property equity or other assets.

By shifting from ‘enterprise first’ to ‘direct-to-consumer’, Cheq puts the power over accrued wages back in the hands of all workers, says Mr. Ayoub: “To achieve a future where Australians are free from payday lender-induced debt traps, the solution must be available to everyone.”

Tarek says Cheq is also aiming to reinvent and pioneer POD as a new industry category by being first in Australia to offer POD direct to consumers. And he is eying markets in the US and India, where he believes a similar solution would have significant take-up.

We think there are some parallels with what AfterPay did with “Buy Now Pay Later” (BNPL) as a category killer, and once again a financial services licence is not required, although in practice Cheq says they would in any case exceed any responsible lending obligations. Cheq is therefore regulated by ASIC.

On average, individuals who registered and completed on-boarding with Cheq took out their first advance 3 days later, with most users stating they liked the piece of mind they had to know that Cheq is there and can be used only when they have a shortfall in funds, according to Tarek.

The most fascinating aspect of this story is the alignment to the customer, with the real purpose centred on financial management and education, rather than turning a quick profit from vulnerable individuals. But it’s an open question whether Cheq is primarily a data analytics firm, a financial services provider, or a financial coach. The truth lies within that triangle. Payday lenders are on notice that their business models are likely to be disrupted.