We look at what the economists are saying about the potential impact. Tourism and exports are likely to be hit – and these are significant to the Australian economy. More broadly, will global growth be hit?

MMT: coming to a politician near you! With Dr. Steven Hail | Nucleus Investment Insights

Nucleus Wealth’s Head of Investment Damien Klassen, Tim Fuller, and Dr. Steven Hail discuss cover “MMT: coming to a politician near you!”

Dr. Hail holds a PhD in Economics and is a lecturer in the topic at the University of Adelaide, where he uses a modern monetary frame to understand macroeconomic issues.

Topics on the agenda included: background on Modern Monetary Theory, countries closest to considering MMT and how Australia could potentially employ it, MMT’s relationship to Bonds & Inflation, legistlative hurdles in the way and much, much more

To listen in podcast form click here: http://bit.ly/NucleusPod

The information on this podcast contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen and Tim Fuller are an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management. Nucleus Wealth is a business name of Nucleus Wealth Management Pty Ltd (ABN 54 614 386 266 ) and is a Corporate Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Ltd – AFSL 515796.

Coronavirus will hurt spending in China, with spillover to global companies

On 29 January, the World Health Organization said that China’s coronavirus has infected nearly 6,000 people domestically so far, with an additional 68 confirmed cases in 15 other countries. The primary impact is on human health. However, the risk of contagion is affecting economic activity and financial markets. The immediate and most significant economic impact is in China but will reverberate globally, given the importance of China in global growth as well as in global company revenue. By sector, the coronavirus will likely have the largest negative impact on goods and services sectors within and outside of China that rely on Chinese consumers

and intermediary products. Via Moody’s.

China’s annual GDP growth forecast unchanged so far, but composition could shift

In our baseline, we expect the outbreak to have a temporary impact on China’s economy and for annual GDP growth in China to remain in line with our forecast of 5.8% in 2020. However, the composition of growth will likely shift because of a dampening of consumption in the first quarter, potentially offset by stimulus measures. Nonetheless, there is still a high level of uncertainty around the length and intensity of the outbreak, and we will review our forecasts as conditions evolve.

Following the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, growth and financial markets in China weakened significantly, but for only a short period. An offsetting rebound limited the overall negative effects on annual growth. But the SARS episode is not a perfect comparison, since the composition of the Chinese economy has changed appreciably since 2003.

Over the past 16 years, the contribution of consumption to China’s economic growth has risen significantly. Therefore, the impact of the coronavirus through the consumption channel may well be higher now. If there is indeed a sharp slowdown in consumption, we would expect macroeconomic policy to be eased in response. This could lead to a shift in the drivers of growth in 2020.

The virus will likely have an effect on the revenue of China’s discretionary travel, transportation, lodging, restaurants, retail and services sectors. However, the impact on offline retail sales could be smaller compared with the weakness following the SARS outbreak because of the rapid shift to online sales in China over the past decade. Non-discretionary consumer demand related to the healthcare sector and medical equipment will likely surge.

Chinese authorities have been proactive in taking quarantine measures to contain the infection, including closing public transportation in some cities and conducting screening in major transportation centers. These measures help contain the spread of infection and promote early treatment, although they add costs and constrain economic activity.

Among the challenges of containing the coronavirus include that it can be contagious during the incubation period, and many of those infected or potentially infected traveled ahead of the Lunar New Year. The next few weeks will be vital for determining the extent of infection and the effectiveness of the quarantine measures.

Loss of productivity will likely weigh on domestic supply as a result of sickness, furloughs, and potential delays in manufacturing production given the government’s decision to extend the Lunar New Year holiday. This situation will likely also reduce private investment, but this effect will be secondary to the effect on consumer spending, and will also depend on the macroeconomic policy response.

Hubei province will bear the brunt of economic impact

The outbreak began in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province and the key transportation and industrial hub in central China. The economic effects on the local area will be significant. Hubei province had expected to record a regional economic growth rate of up to 7.8% in 2020 according to the local authorities, 200 basis points higher than our forecast for China’s total economy. As China’s ninth-most populous and seventh-highest province by GDP, a slowdown in economic activity will pose significant repercussions for the country as a whole.

Hubei’s role in linking China’s eastern coastal area with the central and western regions will extend the ripple effect on neighboring cities and provinces with a higher reliance on service sectors and with higher population densities.

China’s size and interconnectedness amplifies global impact

The fear of contagion risk is already evident in global financial markets. In addition, the negative spillover will also affect countries, sectors and companies that either derive revenue from or produce in China. China has an even higher share in world growth and is even more closely connected with the rest of the world than during the SARS episode. If the outbreak spreads significantly outside China, the burden on healthcare sectors in other affected countries will potentially increase. The revenue of companies and sectors that rely on Chinese demand will be affected as that demand dampens.

The outbreak will also potentially have a disruptive effect on global supply chains. Global companies operating in the affected area may face output losses as a result of the evacuation of workers. Companies operating outside China that have a strong dependence on the upstream output produced from the affected area will also be under pressure because of possible supply chain disruptions resulting from temporary production delays.

Other Asian-Pacific economies are vulnerable to a decline in tourism from China

The outbreak will take a toll on tourism sectors elsewhere in the region, and places outside the region that receive tourists from China. The initial outbreak occurred a few weeks before the Lunar New Year, which has increasingly become a popular time to travel. China has imposed travel bans on outbound group tours to contain the spread of the virus. The fear of contagion could dampen consumer demand and affect tourism, travel, trade, and services in Hong Kong, Macao, Thailand, Japan, Vietnam and Singapore, which have been the top destinations of Chinese tourists in recent years.

China’s National Immigration Administration recorded outbound travel grew about 12% year-on-year to 6.3 million trips during the 2019 Lunar New Year. Following the SARS outbreak, tourism fell sharply in most of these economies, particularly in Singapore and Hong Kong, which were also subject to a relatively high number of infections. We expect the risk of potential negative spillovers to domestic tourism in neighboring countries to be higher than during SARS because Chinese nationals now make up the largest share of visitors to other Asia-Pacific economies. The timing is particularly bad for Japan as it seeks to rebound from the dip in consumption, and presumably real GDP growth, in the last quarter of 2019 following a sales tax hike.

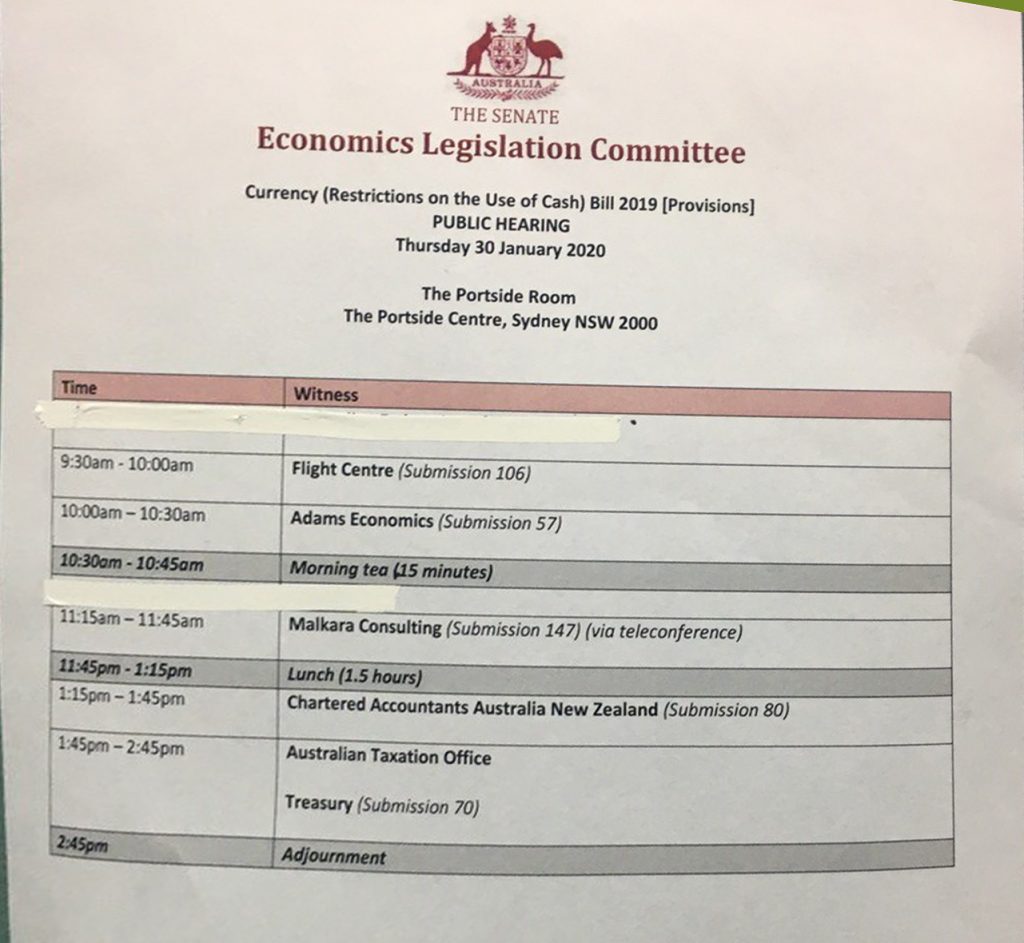

John Adams Hits A Home Run In The Senate Cash Inquiry

The Senate held a hearing in Sydney today relating to the Cash Restrictions Bill.

There were a good number of Australians in the audience.

Economist John Adams made a powerful presentation, linking the proposed cash ban with civil liberties, monetary policy and negative interest rates.

Fed Holds Cash Rate (As Expected)

The Fed kept the cash rate on hold, and there was little change to the commentary, other than a slightly weaker set of words surrounding the consumer.

Growth in household spending moderated toward the end of last year, but with a healthy job market, rising incomes, and upbeat consumer confidence, the fundamentals supporting household spending are solid. In contrast, business investment and exports remain weak, and manufacturing output has declined over the past year. Sluggish growth abroad and trade developments have been weighing on activity in these sectors. However, some of the uncertainties around trade have diminished recently, and there are some signs that global growth may be stabilizing after declining since mid-2018. Nonetheless, uncertainties about the outlook remain, including those posed by the new coronavirus. Overall, with monetary and financial conditions supportive, we expect moderate economic growth to continue.

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in December indicates that the labor market remains strong and that economic activity has been rising at a moderate rate. Job gains have been solid, on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Although household spending has been rising at a moderate pace, business fixed investment and exports remain weak. On a 12‑month basis, overall inflation and inflation for items other than food and energy are running below 2 percent. Market-based measures of inflation compensation remain low; survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1‑1/2 to 1-3/4 percent. The Committee judges that the current stance of monetary policy is appropriate to support sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation returning to the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective. The Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook, including global developments and muted inflation pressures, as it assesses the appropriate path of the target range for the federal funds rate.

In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its maximum employment objective and its symmetric 2 percent inflation objective. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments.

Voting for the monetary policy action were Jerome H. Powell, Chair; John C. Williams, Vice Chair; Michelle W. Bowman; Lael Brainard; Richard H. Clarida; Patrick Harker; Robert S. Kaplan; Neel Kashkari; Loretta J. Mester; and Randal K. Quarles.

CPI Is Still In The Gutter!

We look at the latest from the ABS. The drought and lower dollar is not helping.

What will the RBA do?

Will Coronavirus create a Market Hangover? | Nucleus Investment Insights

Nucleus Wealth’s Head of Investment Damien Klassen, Chief Strategist David Llewellyn Smith and Tim Fuller, discuss “Will Coronavirus create a Market Hangover?”

Topics include the pandemic spreading as the Chinese new year fast approaches, if the data can be trusted, Australian and macro implications if Chinese growth slows, how similar this is to the Chinese SARS outbreak in 2003, and as always we wrap up with our investment outlook

To listen as a podcast click here http://bit.ly/NucleusPod

The information on this podcast contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance.

Damien Klassen and Tim Fuller are an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management. Nucleus Wealth is a business name of Nucleus Wealth Management Pty Ltd (ABN 54 614 386 266 ) and is a Corporate Authorised Representative of Nucleus Advice Pty Ltd – AFSL 515796.

The Retirement Trap

Quirks in the superannuation system in Australia means that some who save more will get less. This highlights again the limitations of the current arrangements.

https://thenewdaily.com.au/finance/superannuation/2020/01/26/pension-super-income-backwards

Can Ratings Agencies Solve The Construction Crisis?

The NSW Government proposes to use Ratings Agencies to solve the poor quality of building construction – what are they thinking?

https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/unit-buyers-to-pay-for-ratings-check-on-dodgy-apartments-under-reforms-20200121-p53t7t.html

Why Retirement Needs A Reboot

We look at a recent report on the future of retirement. There are some big issues on the horizon.

https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us-news/en/articles/media-releases/credit-suisse-research-institute-publishes-study-urging-rethink–202001.html