The RBA released their minutes today, and it continues the uber-positive story. Pity it’s so myopic.

International Economic Conditions

Members commenced their discussion of the global economy by noting that growth in Australia’s major trading partners had been robust in 2018. Growth was expected to ease a little over the subsequent two years, but to remain above potential in 2019. Although there had been little change to the Bank’s outlook for trading partner growth over recent months, the latest forecasts had incorporated a small negative effect from recent tariff changes on growth in a number of economies, including the United States and some east Asian economies. Members discussed the risks to the global outlook from a further escalation in trade tensions and considered the implications for the Australian economy of a scenario in which wages and inflation in the United States pick up by more than expected, given the strength of the US economy.

Growth in the major advanced economies had remained above potential in 2018. Growth in the United States had been strong, supported by the sizeable fiscal stimulus. While US manufacturers had raised concerns about the effects of rising input costs and their competitiveness, business investment intentions had remained strong. Unemployment rates had declined further in the major advanced economies and wages growth had picked up. In the United States, the increase in wages growth had been boosted by workers changing jobs, but recently workers had also been receiving higher wage increases without changing employers. Members observed that inflation in the major advanced economies had increased as a result of higher oil prices and wages growth. However, core inflation had remained low and little changed in some advanced economies, notably Japan and the euro area, but was close to target in others, including the United States.

Growth in China had moderated a little further in the September quarter, following the tightening of financial conditions in late 2017 and early 2018. Although activity in the Chinese services sector had been resilient, conditions had remained weak in the industrial sector and public investment had declined. In response, the Chinese authorities had implemented targeted monetary and fiscal policies to support growth, while maintaining their commitment to containing risks in the financial system. The adverse effect on the Chinese economy from higher tariffs was likely to have been partly offset by policy measures that had been introduced to support affected trading firms. The depreciation of the renminbi over 2018 had also provided support to the economy overall. Elsewhere in Asia, indicators suggested that growth had eased a little recently. The fact that this easing had been most pronounced in growth in exports and industrial production suggested it may have been affected by US–China trade tensions, given the integration of east Asian economies in global manufacturing supply chains.

Commodity prices, in particular those for bulk commodities, had held up by more than had been expected over the previous year. In part, this reflected a number of unforeseen disruptions to supply, particularly for coking coal. Members noted that, in addition, global steel demand had been stronger than anticipated. Oil prices had also risen, which had increased Australia’s terms of trade. Although Australia is a net importer of oil, Australian exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and other oil-related products – the prices of which are linked to oil prices – are larger, following a sustained period of strong growth. Along with a higher starting point as a result of commodity prices having held up, the forecast for Australia’s terms of trade had been revised higher for the next few years owing to a reassessment of the expected strength in global demand for commodities, particularly from China and India.

Domestic Economic Conditions

Members noted that the recent run of economic data suggested that growth in the Australian economy had been higher over the year to the June quarter than earlier forecast, and above estimates of potential growth. Labour market conditions had remained strong and other available indicators pointed to further solid GDP growth in the September quarter. At the same time, inflation in the September quarter had slowed as expected, partly as a result of a large policy-induced decline in childcare prices.

GDP growth was expected to be around 3½ per cent on average over 2018 and 2019. Members noted that growth would be supported by accommodative monetary policy, above-trend growth in Australia’s major trading partners and a stronger profile for the terms of trade. Year-ended GDP growth was expected to ease to around 3 per cent towards the end of 2020 because LNG exports were expected to reach capacity production levels by the end of 2019.

Consumption had continued to grow by around 3 per cent in year-ended terms, despite ongoing low growth in household income. Growth in retail sales had been volatile on a quarterly basis, although in year-ended terms growth had been fairly steady at a relatively modest rate. Conditions had continued to differ across states; retail sales had been relatively strong in Victoria but had declined in Western Australia. Members noted that the strong pace of growth in retail spending online in recent years could be one factor contributing to subdued conditions in retail rental markets. Year-ended growth in household consumption was expected to remain around 3 per cent over the following few years. Growth in household disposable income was forecast to increase to a similar rate.

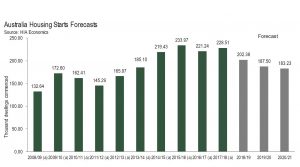

Although residential building approvals had fallen in the September quarter and liaison indicated that pre-sales had become harder to obtain, the large pipeline of work yet to be done was expected to support dwelling investment at a high level over the following year or two. Members noted that population growth was expected to remain fairly strong over the following few years, and that this would provide some support to housing demand. However, there had been reports that bank financing of large development projects had become more difficult, particularly in areas where there had already been substantial development.

Members noted that established housing prices had fallen further in Sydney and Melbourne. After rising by more than apartment prices in preceding years, house prices had fallen by more than apartment prices since 2017. Conditions in the established housing market had been stable in most other cities, although housing prices had declined a little further in Perth in recent months. Rental vacancies had increased in Sydney, consistent with the additions to the stock of housing over the past year, and rent inflation had remained low across the country.

Members observed that business investment had been stronger than forecast a year earlier. The recent strength in non-mining business investment was expected to continue and to make a significant contribution to output growth over the forecast period. Private non-residential construction was expected to be supported by above-average business conditions and the significant pipeline of non-residential construction work that had been approved. Expenditure on machinery and equipment was also expected to rise over the forecast period. Members noted that mining investment had not fallen by as much as expected over the previous year, largely reflecting additional spending on the remaining LNG projects under construction. The trough in mining investment was still expected to occur in late 2018 or early 2019.

Exports had continued to make a significant contribution to growth in output over the preceding year. Resource exports had increased further, mainly because production of LNG had continued to ramp up. Service and manufacturing exports had been supported by strong global growth and the depreciation of the Australian dollar over 2018. The persistent drought conditions in New South Wales and bordering regions in Queensland and Victoria had led to a short-term boost to rural exports because livestock slaughter rates had increased and some grain crops had been harvested early to take advantage of higher feed prices. However, the medium-term outlook for farm sector production had been revised lower.

Labour market conditions had been stronger than expected. Members noted that much of the employment growth had been in full-time employment and that the participation rate had remained at a high level. The unemployment rate had declined to 5 per cent in September. Unemployment rates in most states had trended lower in recent months and were particularly low in New South Wales and Victoria. The unemployment rate was now expected to decline gradually to around 4¾ per cent by mid 2020, although members noted that some leading indicators of labour demand suggested there could be a more pronounced decline in the unemployment rate in the near term.

The improved labour market outlook had led to a modest upward revision to the outlook for wages growth. The recent increases in award and minimum wages were expected to have provided a small boost to wages growth in the September quarter. Members discussed the wage increases associated with recent enterprise bargaining agreements and uncertainties around the extent to which these and ongoing negotiations might flow through to overall wages growth. Members noted that average real earnings had not increased for six years and that wages growth was a key uncertainty for both future consumption growth and inflation.

Year-ended inflation had remained low in the September quarter. CPI inflation was 1.9 per cent over the year to the September quarter and had been around 2 per cent since early 2017. Underlying inflation was a little below ½ per cent in the September quarter and around 1¾ per cent over the year. As expected, the quarterly outcome incorporated a large decline in administered prices, reflecting a sharp decline in childcare prices owing to changes in government subsidies and a moderation in utilities inflation. The noticeable step-down in administered price inflation from earlier years was expected to be temporary, although members noted that future outcomes depended on possible government initiatives to reduce cost-of-living pressures. Inflation in the cost of new housing and rents had also been subdued in the September quarter. Inflation was still forecast to increase gradually over time as spare capacity in the economy declines. The brighter outlook for economic activity and the labour market, compared with three months earlier, had led to a small upward revision to the inflation forecasts.

Financial Markets

Members commenced their discussion of financial market developments by noting that financial conditions in the advanced economies remained accommodative, although they had tightened somewhat recently.

In October, equity prices had declined sharply across the major markets. Analysts had attributed the fall to a range of factors, including higher bond yields, concerns that the pace of earnings growth would decline given trade tensions and building cost pressures, and elevated valuations (particularly in the United States). Members noted, however, that recent corporate earnings, especially in the United States, had grown strongly and had mostly been above forecasts.

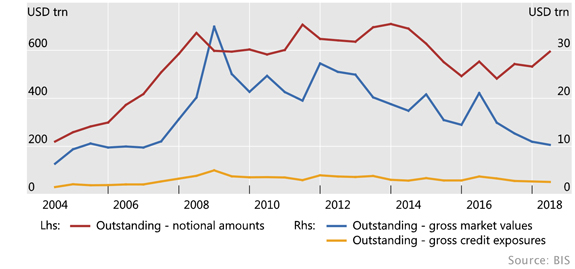

Members observed that there had generally been little spillover from equity markets to other financial markets. Money market and corporate bond spreads had increased a little but remained relatively low. Term premia for sovereign debt and exchange rate volatility also remained low in the major markets. Members noted that the leveraged loan market had grown rapidly, particularly in the United States, and corporate funding had increasingly shifted to the securities markets rather than bank finance.

Monetary policy in the major economies remained accommodative. Members noted that financial market pricing continued to imply that policy settings of central banks are on divergent paths, reflecting differences in spare capacity and/or the inflation outlook across economies. In the United States and Canada, markets were pricing in a further tightening in monetary policy over the coming year. Financial market pricing continued to imply a lower path for the US federal funds rate than suggested by the median projection of Federal Open Market Committee members. Market pricing implied a smaller increase in policy rates over the coming year in the United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden, with rates expected to remain very low in these economies. By contrast, market pricing was consistent with policy rates remaining steady over the following year in Australia and New Zealand, where policy rates had not been lowered to the extent they had in some other economies. In Japan, the euro area and Switzerland, market pricing remained consistent with maintenance of the highly accommodative monetary policy settings in these economies.

Members observed that the divergent monetary policy paths had been reflected in long-term government bond yields, which had increased in the United States and Canada over the prior year, but had been broadly unchanged in other major markets and Australia. Members noted that long-term government bond yields in Australia were now clearly below those in the United States as a result. Members also noted that long-term government bond yields remained low by historical standards in the major markets, with inflation expectations contained and term premia particularly low.

In Italy, the spread of Italian government bond yields over German Bunds had risen further in October, following the rejection by the European Commission of the Italian Government’s draft budget. However, Italian yield spreads remained below the levels seen during the European debt crisis in 2012 and there had been limited spillovers to other European bond markets. Nevertheless, ongoing concerns about Italian fiscal policy settings were likely to remain a focus for financial market participants.

Financial conditions in emerging markets had stabilised recently, as earlier political and macro-financial concerns in Turkey, Argentina and Brazil had eased somewhat. After depreciating sharply since the beginning of 2018, these economies’ exchange rates had appreciated over the preceding couple of months. This followed some corrective policy responses and an easing in perceived political risk. Exchange rate volatility had also declined from its recent peak across emerging market economies more broadly. However, members noted that there remained a risk that capital outflows from emerging markets could broaden and intensify, prompting a more significant tightening of financial conditions.

In China, the authorities had implemented further targeted measures to ease financial conditions in response to slower growth, while balancing their commitment to containing risks in the financial system. In October, banks’ reserve requirement ratios were cut by another 1 percentage point, following earlier measures to ensure ample bank liquidity. The decline in Chinese share prices over 2018 had also recently prompted the authorities to announce measures to support the equity market. The renminbi exchange rate had depreciated over 2018 in response to concerns about trade protection and the outlook for growth, as well as the policy measures targeted at easing financial conditions. However, unlike the 2015 depreciation episode, there had been few signs of large-scale capital outflows or direct foreign exchange intervention by the authorities.

The Australian dollar had depreciated a little over the course of 2018, but remained in the fairly narrow range observed over recent years on a trade-weighted basis. Members observed that this had reflected offsetting effects on the exchange rate from higher commodity prices, on the one hand, and the decline in Australian bond yields relative to those in other major markets, on the other hand.

Members noted that Australian banks’ funding costs remained a little higher than in 2017, reflecting the increase in short-term money market rates over the first half of 2018. More recently, the spread of bank bill swap rates relative to overnight indexed swaps (OIS) had declined marginally over the preceding month, while the spread of US LIBOR to OIS had increased. Information from liaison suggested that there had been little change in domestic money market conditions in recent months. The modest increase in funding costs earlier in the year had been passed on by most lenders to existing borrowers with variable-rate business and housing loans.

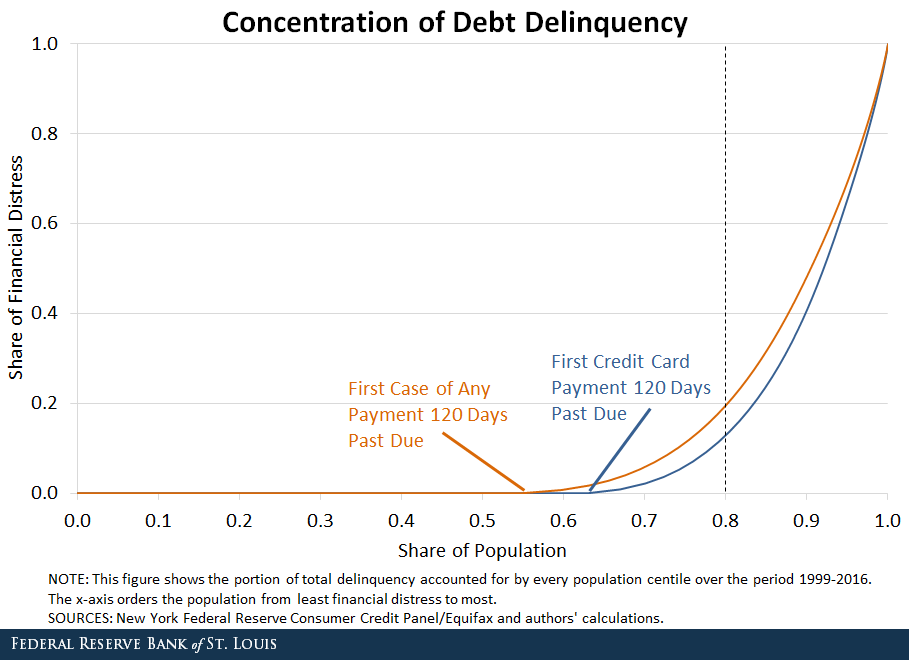

The pace of overall credit growth had been maintained in recent months, as slowing housing credit growth had been offset by a pick-up in business credit growth. The easing in growth in housing credit had reflected a slowing in growth in lending by the major banks. By contrast, growth in housing lending by other authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) had picked up. Housing lending by non-ADIs had continued to grow strongly, although these institutions’ share of total housing credit remained small. Members noted that the easing in housing credit growth had been accounted for largely by slower growth in credit extended to investors, which was now close to zero. Growth in lending to owner-occupiers had eased more gradually and remained around 6½ per cent in six-month-ended annualised terms.

Members noted that the easing in housing credit growth was likely to reflect both tighter lending conditions and some weakening in demand. Stricter lending criteria had reduced maximum loan amounts. At the same time, however, interest rates offered on new loans remained lower than interest rates on outstanding loans, consistent with banks continuing to compete for new borrowers.

Financial market pricing implied that the cash rate was expected to remain unchanged for a considerable period.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

As part of a regular annual review process, members considered how the domestic economy had evolved over the preceding year relative to the Bank’s forecasts of a year earlier. Members noted that the magnitude of forecast errors for key variables, including GDP growth, the unemployment rate and inflation, had been smaller than the historical averages. Overall, GDP growth had been higher than expected at the time of the November 2017 Statement on Monetary Policy. While most components of GDP had turned out to be a little stronger than expected, the main source of the upward surprise had been business investment, owing to unexpected strength in both mining and non-mining investment. In addition, the terms of trade had been higher than expected over the previous year and the Australian dollar had depreciated. Consistent with these developments, labour market outcomes had also been stronger than expected a year earlier and more progress had been made in reducing unemployment than expected. Despite this, wages growth and underlying inflation had evolved largely as expected. Overall, members noted that the economic outcomes over the preceding year had been consistent with the economy continuing on its forecast trajectory of gradually declining spare capacity, with a correspondingly gradual increase in wages growth and inflation.

In the context of the annual review of the forecasts, members also reviewed arguments that had been advanced by various commentators during the preceding year for an increase or decrease in the cash rate. Some of these arguments relied on different assessments than had been made by the Board in relation to the benefits of seeking faster progress on the Bank’s inflation and unemployment rate objectives, versus the risks to longer-term sustainable growth from further increases in household debt. Other arguments for a change in the cash rate relied on an alternative assessment about the economic outlook and/or the risks around the outlook. Arguments in favour of an increase in the cash rate included that the economy had more momentum than assessed by the Bank; financial stability risks from high levels of household debt required higher interest rates; and a higher cash rate would create room to cut the cash rate in future in response to an adverse event. The prime argument in favour of a decrease in the cash rate was that easier monetary policy could lead to faster progress in achieving the Bank’s monetary policy objectives.

Members discussed how different scenarios could affect the monetary policy decision, noting that the appropriate policy response would depend on the specifics of the situation, including the underlying factors driving economic developments. For example, in the event of a marked change in the strength of the global economy, the effect on the Australian economy – and thus the appropriate monetary policy response – would depend on any associated move in the exchange rate of the Australian dollar. Members also discussed various scenarios related to the labour market and household expenditure.

Turning to the current month’s decision, members noted that the global economy had continued to grow strongly and global financial conditions remained accommodative, although conditions had tightened somewhat recently. Most advanced economies were growing at above-trend rates and their labour markets had continued to tighten. This had led to a noticeable pick-up in wages growth. In some economies, most notably the United States, inflationary pressures were building. Growth in China had slowed a little and the authorities had responded to weakness in some sectors of the economy with targeted policy measures, while continuing to pay close attention to risks in the financial sector. Members noted that the direction of international trade policy continued to be a significant risk to the global outlook.

Against the background of rising global inflationary pressures, a few central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, were expected to continue to reduce the degree of monetary policy accommodation gradually. Changes in the expected paths of monetary policy over the preceding year had been reflected in changes to financial market pricing, most notably a broad-based appreciation of the US dollar. The associated modest depreciation of the Australian dollar over 2018 was likely to have been helpful for domestic economic growth.

Members noted that economic conditions in the Australian economy had continued to improve and had been a little stronger than expected. The outlook for growth had been revised a little higher, mainly as a result of upward revisions to history and recent strong data. Year-ended GDP growth was expected to remain above 3 per cent over 2019, before slowing to around 3 per cent in 2020. Members observed that the outlook for consumption continued to be a source of uncertainty in an environment of slow growth in household incomes, high debt levels and easing conditions in housing markets in some parts of the country. These conditions warranted close monitoring. At the same time, investment had been stronger than expected over the previous year and business conditions were positive; if the recent momentum were to be sustained, business investment could turn out to be stronger than currently expected. However, the drought had led to difficult conditions in parts of the farm sector.

Conditions in the labour market had also been stronger than expected and forward-looking indicators of labour demand continued to point to ongoing strength in the near term. As a result, the forecast for the unemployment rate had been revised lower and the forecast for wages growth had been revised slightly higher. Members noted that there continued to be uncertainty about the degree of spare capacity in the labour market and the extent and speed of any pick-up in wages growth relative to the gradual increase incorporated in the latest forecasts. They acknowledged that a gradual increase in wages growth was likely to be necessary for inflation to be sustainably within the target range.

Underlying inflation had remained low and stable at around 1¾ per cent, consistent with the previous forecasts, despite stronger-than-expected economic activity. Although there was a possibility of further declines in administered prices in the year ahead, underlying inflation was expected to pick up gradually over the forecast period, to be a little above 2¼ per cent in 2020.

Conditions in the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets had continued to ease, following significant growth over preceding years. Rent inflation had remained low. Housing credit growth had declined, particularly for investors, but had continued to be higher than growth in household income. Credit conditions were tighter than they had been for some time, partly because lending standards had been tightened following the introduction of supervisory measures to help contain the build-up of risk in household balance sheets. At the same time, home lending rates had remained low and there was strong competition for borrowers of high credit quality.

Taking account of the available information on current economic and financial conditions, as well as the latest forecasts, members assessed that the current stance of monetary policy would continue to support economic growth and allow for further gradual progress to be made in reducing the unemployment rate and returning inflation towards the midpoint of the target. In these circumstances, members continued to agree that the next move in the cash rate was more likely to be an increase than a decrease, but that there was no strong case for a near-term adjustment in monetary policy. Rather, members assessed that it would be appropriate to hold the cash rate steady and for the Bank to be a source of stability and confidence while this progress unfolds. Members judged that holding the stance of monetary policy unchanged at this meeting would be consistent with sustainable growth in the economy and achieving the inflation target over time.

The Decision

The Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1.5 per cent.