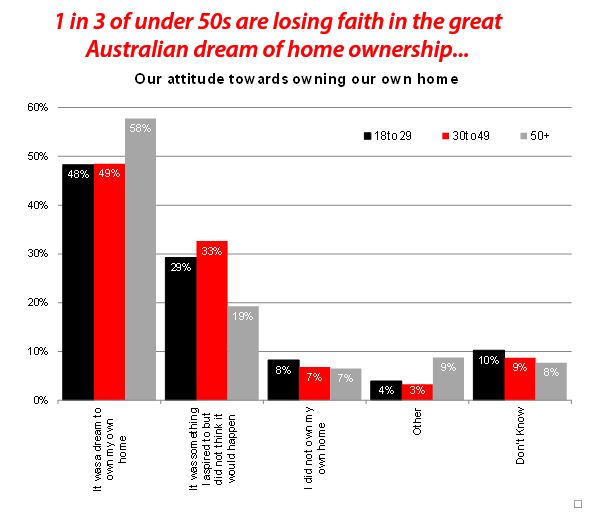

The US Financial Stability Oversight Council has published their 2017 Annual Report. Their mandate under the Dodd-Frank Act is to identify risks to the financial stability of the US, promote market discipline and respond to emerging threats. At more than 150 pages, its is a long read, but well worth the effort. Also compare and contrast with the high household debt levels here!

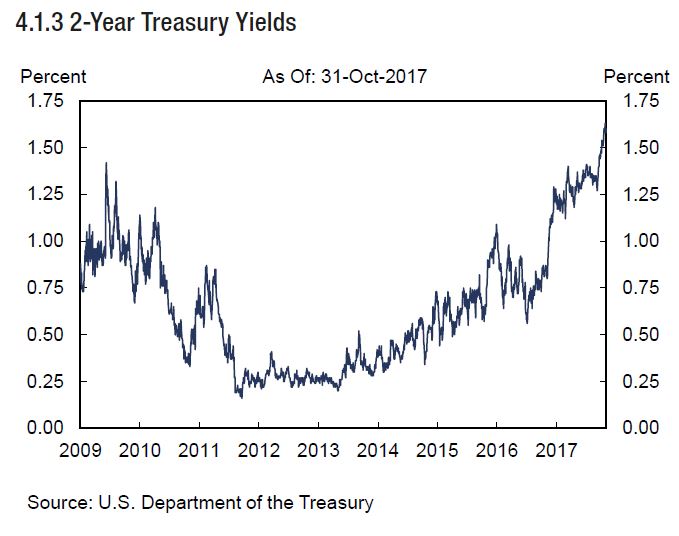

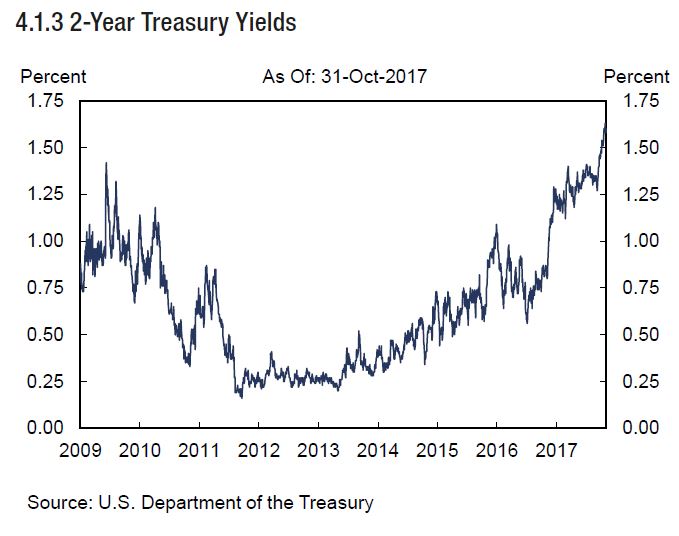

A couple of things caught my attention. First, the rise in the 2-Year Treasury Bonds, as rate are normalized. Rates are in their way up.

Yields on 2-year Treasury notes fell in the first half of 2016, reaching a low of 0.56 percent in July before reversing course (Chart 4.1.3). The 2-year Treasury yield has since risen 104 basis points to 1.60 percent, as of October 2017. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised its target range for the federal funds rate 25 basis points four times since December 2016. Also, in October 2017, the Federal Reserve began normalizing its balance sheet.

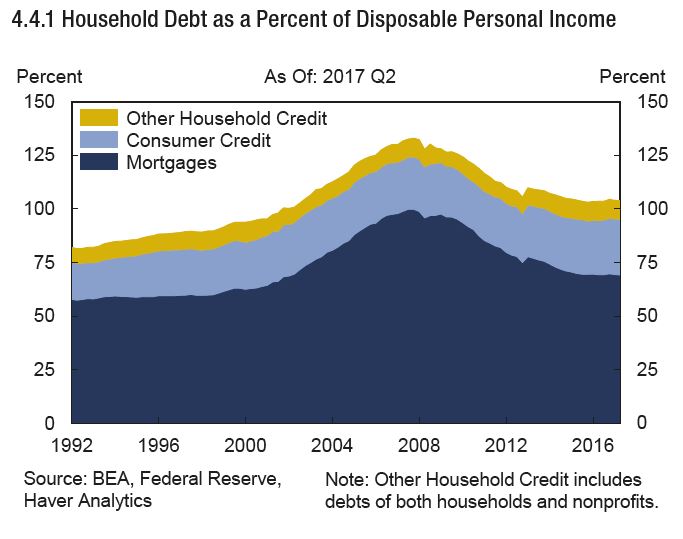

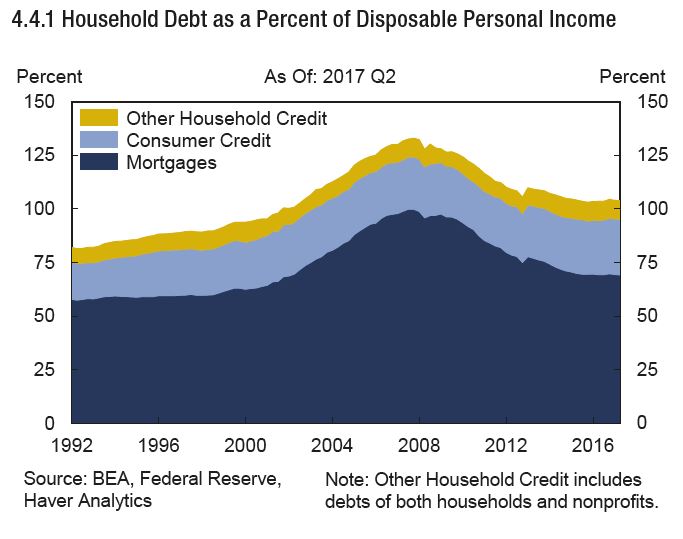

Next, household debt to disposable income is around 100%, significantly lower than Australian households, and on a very different trajectory.

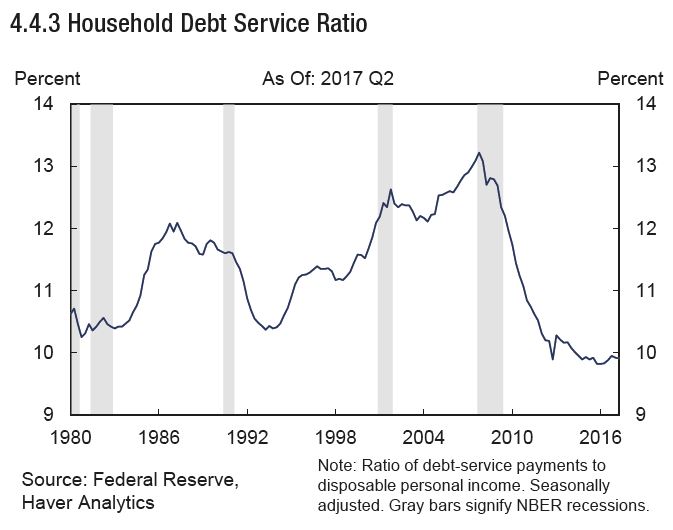

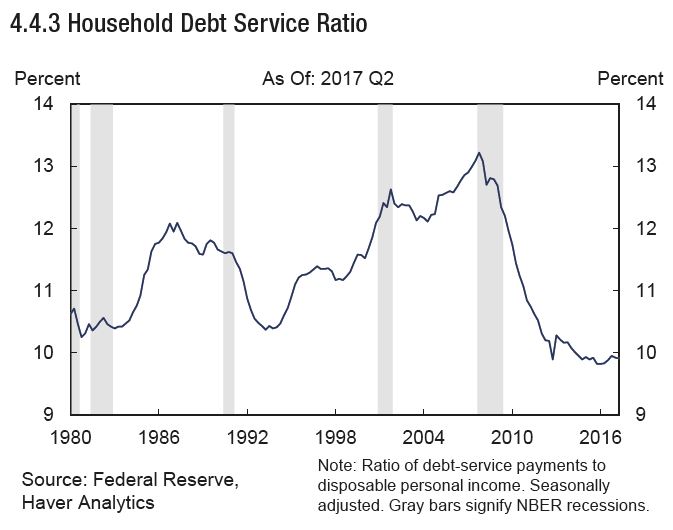

There has been significant growth in auto loans and student loans, compared with mortgage debt. But the household debt service ratio is lower than here, a low interest rates helped keep the debt service ratio—the ratio of debt service payments to disposable personal income—unchanged in 2016 and the first half of 2017, near a 30-year low (Chart 4.4.3). Although the ratio of debtservice payments to disposable personal income for consumer credit has edged steadily upward since 2012, this trend has been fully offset by a decrease in the service ratio of mortgage debt.

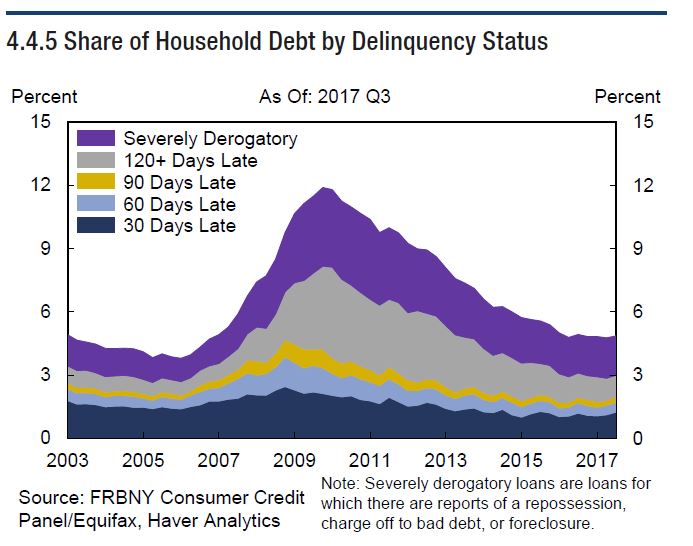

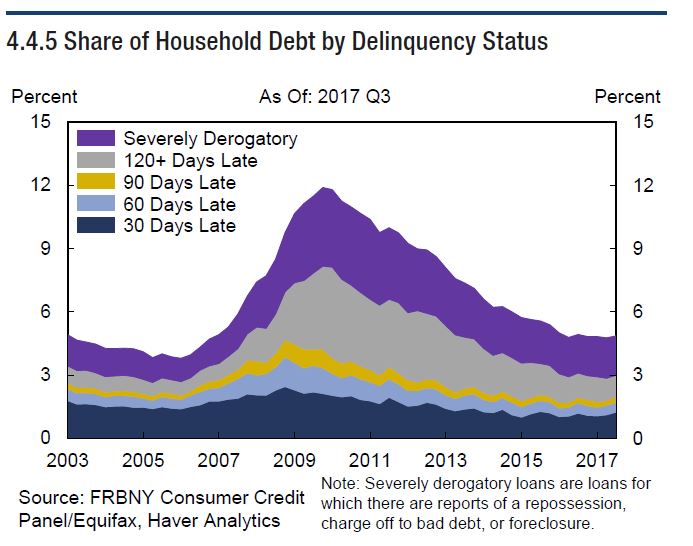

Finally loan delinquency is lower now than back in 2009.

Finally loan delinquency is lower now than back in 2009.

Continued decreases in delinquency rates on home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) and mortgage debt pushed household debt delinquencies to less than 5 percent, the lowest year-end level since 2006 (Chart 4.4.5). Decreased overall delinquency among subprime borrowers, continued write-downs of mortgage debt accumulated during the pre-crisis housing bubble, and a shift from subprime to prime mortgage balances drove the decline. The delinquency rate on student loans remained unchanged at 11 percent over the past few years after nearly doubling between 2003 and 2013. Despite elevated delinquency rates on student loans, default risk is generally limited for private lenders, since the federal government owns or guarantees most student loan debt outstanding. Signs of stress have emerged in auto lending in recent years, driven by increased subprime borrower delinquency. In the second quarter of 2017, auto loan balances that were delinquent for at least 90 days reached 3.9 percent of total auto loan balances, up from 3.3 percent three years prior. In recent quarters, credit card delinquency rates have increased slightly, and the percent of credit card loans that were delinquent for at least 90 days increased to 4.4 percent, compared to 3.7 percent three years prior. Despite this trend, the balance of credit card debt that was delinquent for at least 90 days has remained relatively stable at 7.4 percent in the second quarter of 2017, compared to 7.8 percent three years prior.

They discussed some highly relevant issues:

Managing Vulnerabilities in an Environment of Low, but Rising, Interest Rates – In previous annual reports, the Council identified vulnerabilities that arise from a prolonged period of low interest rates. In particular, as investors search for higher yields, some may add assets with higher credit or market risks to their portfolios. They may also use more leverage or rely on shorter-term funding. These actions tend to raise the overall level of financial risk in the economy and may put upward pressure on prices in certain markets. If prices in those markets were to fall sharply, owners could face unexpectedly large declines in their overall portfolio value, potentially creating conditions of financial instability. Although both short-term and long-term interest rates have risen since the last annual report, the consequences of past risk-taking may persist for some time. While the rise in short-term rates has benefitted net interest margins (NIMs) and net interest income at depository institutions and broker-dealers, a flatter yield curve and expectations for higher funding costs going forward may increasingly lower the earnings benefits from higher interest rates. In addition, the transition to higher rates may expose vulnerabilities among some market participants through a reduction in the value of their assets or an uncertain rise in costs of funding for depository institutions. These vulnerabilities can be mitigated by supervisors, regulators, and financial

institutions closely monitoring increased risk-taking incentives and risks that might arise from rising rates.

Housing Finance Reform – The government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) are now into their tenth year of conservatorship. While regulators and supervisors have taken great strides to work within the constraints of conservatorship to promote greater investment of private capital and improve operational efficiency with lower costs, federal and state regulators are approaching the limits of their ability to enact wholesale reforms that are likely to foster a vibrant, resilient housing finance system. Housing finance reform legislation is needed to create a more sustainable system that enhances financial stability.

They called out a number of areas for focus where technology intersects finance:

Cybersecurity – As the financial system relies more heavily on technology, the risk that significant cybersecurity incidents targeting this technology can prevent the financial sector from delivering services and impact U.S. financial stability increases. Through collaboration and partnership, substantial gains have been made by both government and industry in response to cybersecurity risks, in part by refining their shared understanding of potential vulnerabilities within the financial sector. It is important that this work continue and include greater emphasis on understanding and mitigating the risk that significant cybersecurity incidents have business and systemic implications.

Financial Innovation – New financial market participants and new financial products can offer substantial benefits to consumers and businesses by meeting emerging needs or reducing costs. But these new participants and products may also create unanticipated risks and vulnerabilities. Financial regulators should continue to monitor and analyze the effects of new financial products and services on consumers, regulated entities, and financial markets, and evaluate their potential effects on financial stability.

And finally, a range of other material structural issues:

Central Counterparties – Central counterparties (CCPs) have the potential to provide considerable benefits to financial stability by enhancing market functioning, reducing counterparty risk, and increasing transparency. These benefits require that CCPs be highly robust and resilient. Regulators should continue to coordinate in the supervision of all CCPs that are designated as systemically important financial market utilities (FMUs). Member agencies should continue to evaluate whether existing rules and standards for CCPs and their clearing members are sufficiently robust to mitigate potential threats to financial stability. Agencies should also continue working with international standard-setting bodies to identify and address areas of common concern as additional derivatives clearing requirements are implemented in other jurisdictions. Evaluation of the performance of CCPs under stress scenarios can be a very useful tool for assessing the robustness and resilience of such institutions and identifying potential operational areas for improvement. Supervisory agencies should continue to conduct these exercises. Regulators should also continue to monitor and assess interconnections among CCPs, their clearing members, and other financial institutions; consider additional improvements in

public disclosure; and develop resolution plans for systemically important CCPs.

Short-Term Wholesale Funding – While some progress has been made in the reduction of counterparty risk exposures in repurchase agreement (repo) markets in recent years, the potential for fire sales of collateral by creditors of a defaulted broker-dealer remains a vulnerability. The SEC should monitor and assess the effectiveness of the MMF rules implemented last year. Regulators should also monitor the potential migration of activity to other cash management vehicles and the impact of money market developments on other financial markets and institutions.

Reliance on Reference Rates – Over the past few years, regulators, benchmark administrators, and market participants have worked toward improving the resilience of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) by subjecting the rate and its administrator to more direct oversight, eliminating little-used currency and tenor pairings, and embargoing the submissions of individual banks to the panel for a three-month period. However, decreases in the volume of unsecured wholesale lending has made it more difficult to firmly ground LIBOR submissions in a sufficient number of observable transactions, creating the risk that publishing the benchmark may not be sustainable. Regulators and market participants have been collaborating to develop alternatives to LIBOR. They are encouraged to complete such work and to take appropriate steps to mitigate disruptions associated with the transition to a new reference rate.

Data Quality, Collection, and Sharing – The financial crisis revealed gaps in the data needed for effective oversight of the financial system and internal firm risk management and reporting capabilities. Although progress has been made in filling these gaps, much work remains. In addition, some market participants continue to use legacy processes that rely on data that are not aligned to definitions from relevant consensus-based standards and do not allow for adequate conformance and validation to structures needed for data sharing. Regulators and market participants should continue to work together to improve the coverage, quality, and accessibility of financial data, as well as data sharing between and among relevant agencies.

Changes in Financial Market Structure and Implications for Financial Stability – Changes in market structure, such as the increased use of automated trading systems, the ability to quote and execute transactions at higher speeds, the increased diversity in the types of liquidity providers in such markets, and the expansion in trading venues all have the potential to increase the efficiency and improve the functioning of financial markets. But such changes and complexities also have the potential to create unanticipated risks that may disrupt financial stability. It is therefore important that market participants and regulators continue to try to identify gaps in our understanding of market structure and fill those gaps through the collection of data and subsequent analysis. In addition, evaluation of the appropriate use or expansion of coordinated tools such as trading halts across interdependent markets, particularly in periods of market stress, will further the goal of enhancing financial stability, as will collaborative work by member agencies to analyze developments in market liquidity.

Prevailing explanations of the decline in real interest rates since the early 1980s are premised on the notion that real interest rates are driven by variations in desired saving and investment.