Interesting speech from RBA’s Guy Debelle, highlighting issues around measuring an number of economic factors. He calls out CPI as one area of uncertainly, especially as the ABS does a quarterly report (unlike many other countries who publish monthly) and the changes in weightings which will impact ahead. There is a lot of noise in the data…!

For inflation – which is also published quarterly in Australia – we won’t get an official read on the current rate until the December quarter Consumer Price Index (CPI) is released in late January, three months from now. In most other countries, the CPI is published monthly, so the wait to get an assessment on current inflation is not so long elsewhere.

More timely and more frequent estimates of output and inflation are not unambiguously desirable. There is clearly a trade-off between timeliness and accuracy. But, in the case of inflation, a more frequent estimate would help to identify changes in the trend in inflation sooner; it probably comes with more noise, but we have ways to deal with that. Any reading on inflation always contains varying degrees of signal and noise about the ‘true’ inflation process. At the moment, we need to wait three more months to gain a better understanding as to whether any particular read on inflation is signalling a possible change in trend or is just noise. That is one of the reasons why the RBA has long advocated a shift to monthly calculation of the CPI.

That said, we do not depend solely on GDP and the CPI to assess the current state of the economy. We spend a lot of time and effort piecing together information from a large number of other sources. These include higher frequency and more timely data, including from the ABS, but also from a wide range of other data providers. The information we obtain from talking to people, particularly through our business liaison program, is also invaluable.

The question then arises as to how we can filter the information we receive from all these different sources to gain an overall picture about inflation and the state of the overall economy. Take GDP as an example. Some of the data released before the national accounts, such as monthly retail sales and international trade, feed directly into the calculation of GDP. So we have a direct read on those. We ‘nowcast’ other components of GDP using data that are more timely. Let me illustrate for household consumption. We get a good measurement of consumption of goods by looking at monthly retail sales and sales of motor vehicles and fuel. But there is very little timely information on household consumption of services, so the nowcast of this component relies more on statistical relationships. Some of these relationships are pretty weak, so we also supplement this with information on sales from our regular discussions with our business liaison contacts. This then gives us an estimate of consumption for the quarter. To get a preliminary nowcast for GDP growth for the quarter, we aggregate our best estimate for each of the relevant components. We then ask ourselves whether this estimate is consistent with other information that we have, such as the monthly labour market data, as well as predictions from our macro forecasting models.

The nowcast can be then updated with new information as it comes to hand. That said, my observation from a couple of decades of forecasting is that your first estimate of GDP (three months out) is often the best, and that additional information is often noise rather than signal.

Measurement uncertainty

Aside from when data are published, uncertainty about the present also arises from how things are measured. This takes two forms. First, there is the methodology used to actually measure the variable in question. Second, there are the revisions to data after they were first published.

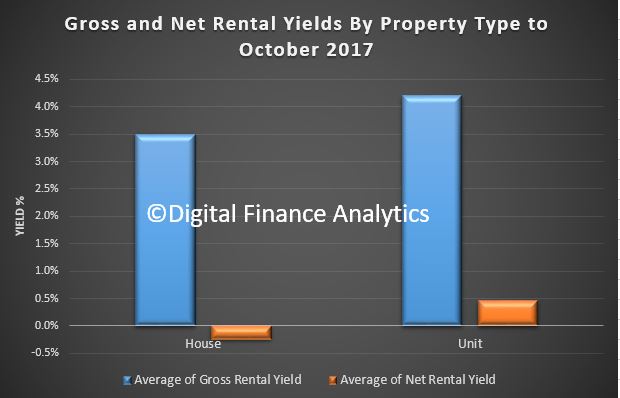

On the first, a good example is the CPI. The CPI measures prices for a large number of items purchased by households. When aggregating these to calculate the overall consumer price index, each item is assigned a weight based on its average share of household expenditure. That is, the aim is to weight each price by the amount households spend on it, on average, in the period in question.

Obviously, these weights can change through time. But the weights used in the CPI are only updated each time the ABS conducts a Household Expenditure Survey, which, in recent times, has been every five or six years.

In between each household expenditure survey, a number of things can happen. First of all, some new goods and services can come along that weren’t there before. One example you might think of is a mobile phone. Though it’s not quite that straightforward, as before mobile phones, households spent money on landline phone bills and on cameras. So often these ‘new’ goods are providing similar services to something that was there before. Nevertheless, the ABS needs to take account of these new goods coming in, as well as some old items dropping out.

Secondly, households adjust their spending in response to movements in prices and income. In practice, households tend to substitute towards items that have become relatively less expensive, and substitute away from items that have become relatively more expensive. But the expenditure weights in the CPI are only updated every five or six years. Over time, the effective expenditure weights in the CPI become less representative of actual household expenditure patterns. That is, they are putting more weight on items whose prices are rising than households are actually spending on them. This introduces a bias in the measured CPI – known as substitution bias – which only is addressed when the expenditure weights are updated. Because households tend to shift expenditure towards relatively cheaper items, infrequent updating of weights tends to overstate measured CPI inflation.

The ABS will very shortly update the expenditure weights in the CPI. Because of substitution bias, history suggests that measured CPI inflation has been overstated by an average of ¼ percentage point in the period between expenditure share updates. While we are aware of this bias, we are not able to be precise about its magnitude until the new expenditure shares are published, because past re-weightings are not necessarily a good guide. It is also not straightforward to account for this in forecasts of inflation. However, from a policy point of view, the inflation target is sufficiently flexible to accommodate the bias, given its relatively small size.

Going forward, the ABS will update the expenditure shares annually, rather than every five or six years. This will reduce substitution bias in the measured CPI.