Financial stability risks have taken on increased importance in monetary policy deliberations of Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor Philip Lowe – far more than under his predecessor, Glenn Stevens.

The importance of managing those risks, especially in the household sector, were scattered, yet again, through the RBA’s November monetary policy statement this week.

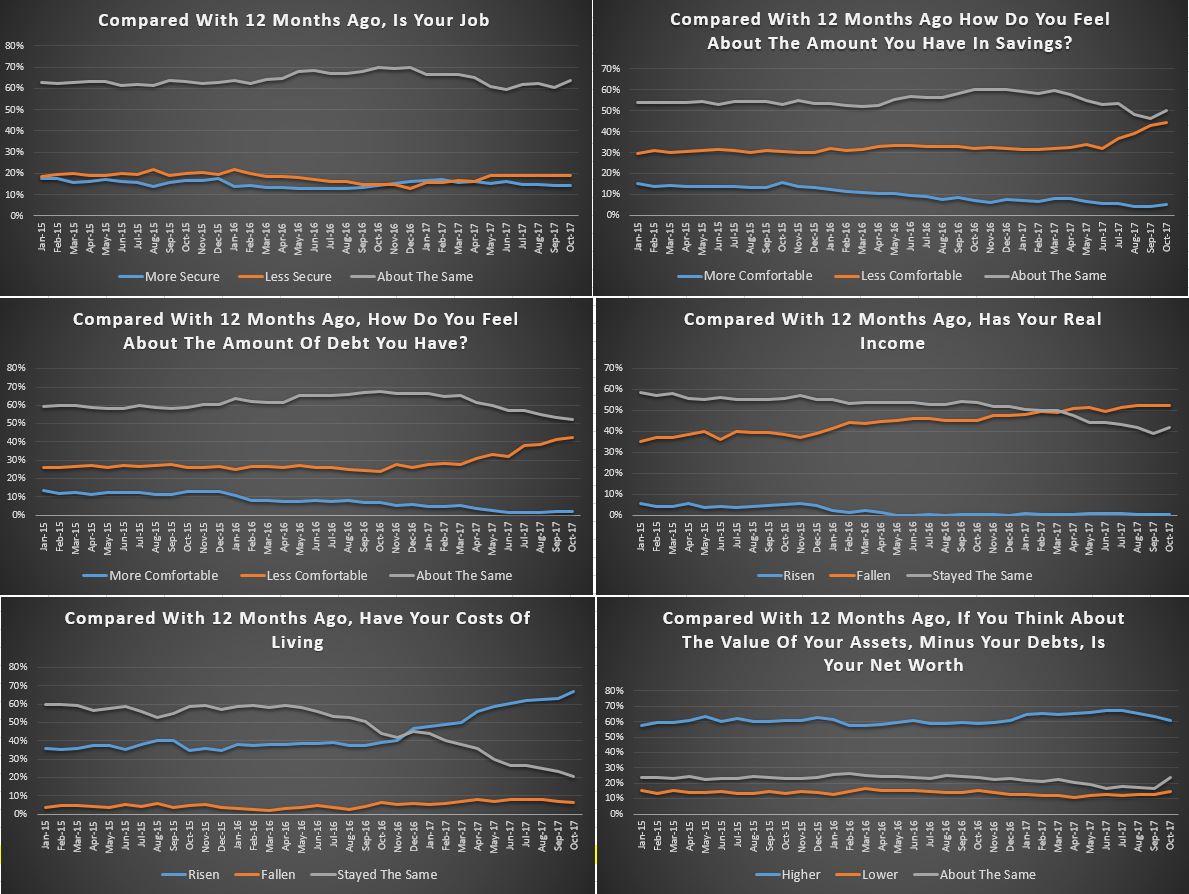

“Household incomes are growing slowly and debt levels are high,” Lowe said, elaborating on the uncertain outlook for household consumption given recent weakness in retail sales.

And, on household debt specifically, he said that “growth in housing debt has been outpacing the slow growth in household income for some time,” repeating the warning he issued in October.

Clearly, managing these risks, in his opinion, are of utmost importance.

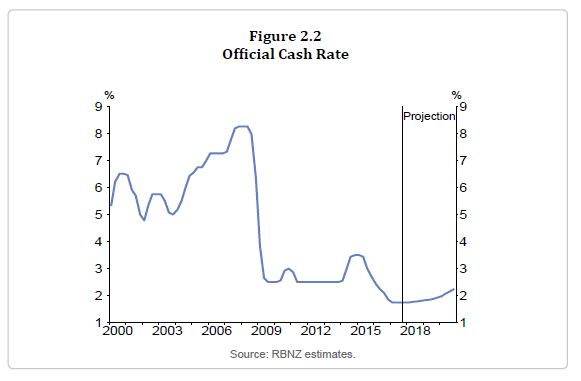

Despite persistently low inflationary pressures, weak economic growth, softening household spending levels and strength in the Australian dollar, Lowe has left interest rates unchanged since his took over as Governor in September last year, a distinct shift in mindset to what was seen in prior years.

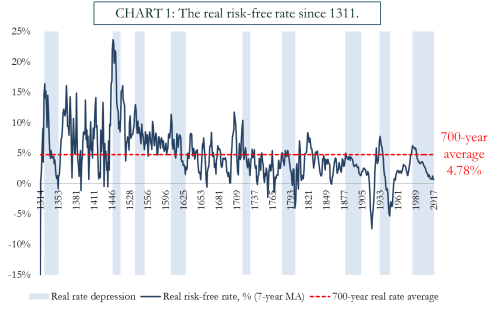

Gone are the days of rates moving like clockwork in the month following a quarterly consumer price inflation (CPI) report, replaced instead by a broader focus that appears to place less emphasis on the inflation outlook and more on what could happen in other parts of economy should rates be lowered again, especially the east coast property market.

The era of continually lowering rates to bring inflation back into the bank’s 2-3% target in a more timely manner now appears to be over.

Lowe, as many Australians are acutely aware, knows all too well what happened in 2016 when the RBA cut rates twice in an attempt to boost inflationary pressures.

Property prices in Sydney and Melbourne surged again, thanks largely to a pickup in investor activity. Household debt levels, as a response, rose from already elevated levels, far outpacing growth in household incomes.

Household leverage, therefore, continued to increase, helping to explain why Lowe has been reluctant to cut interest rates further, pouring even more fuel on an already hot east coast property market.

As he told parliamentarians earlier this year, further rate cuts “would probably push up house prices a bit more, because most of the borrowing would be borrowing for housing.”

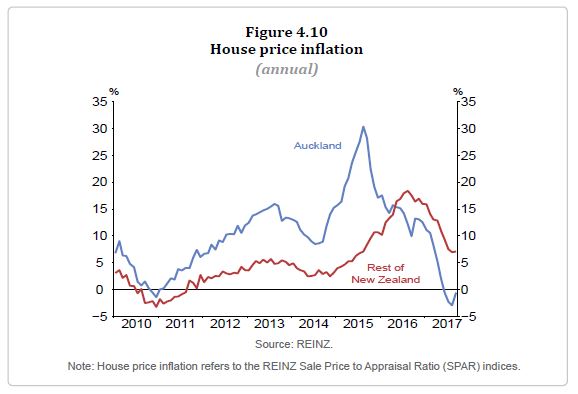

Instead of hiking rates to mitigate financial stability risks as was usually the case in the past, the RBA, working with other members of Australia’s Council of Financial Regulators — APRA, ASIC and Treasury — decided to go down another path, introducing tougher macroprudential restrictions on interest-only lending earlier this year, building upon the 10% annual cap on investor housing credit growth introduced by APRA in late 2014.

On the early evidence, it’s succeeded in helping to cool the rampant Sydney and Melbourne property markets.

According to data from CoreLogic, Sydney house prices have fallen in each of the past two months, coinciding with auction clearance rates falling to the lowest level since January 2016.

Price growth in Melbourne has also slowed, logging the smallest quarterly increase since mid-2016 in the three months to October. Clearance rates there have also fallen from the highs seen earlier this year.

With prices in Sydney going backwards and those in Melbourne, it saw national house prices, on a weighted basis, remain unchanged last month.

As Lowe said earlier this week, “housing prices have shown little change over recent months”, partially attributing the slowdown to tougher macroprudential measures introduced in late March.

“Credit standards have been tightened in a way that has reduced the risk profile of borrowers,” he said.

However, while this, along with other factors such as affordability constraints and out-of-cycle mortgage rate increases for some borrowers, has undoubtedly helped to slow the housing market without having to resort to rate hikes, Lowe still has a problem that remains unaddressed.

No only is growth in housing debt outpacing household incomes, it’s actually widened further this year despite tighter lending restrictions.

This excellent chart from ANZ shows the quandary facing Lowe.

It shows Australia’s household debt to income ratio, expressed as an annual percentage change.

“The most recent RBA data on private sector credit showed that in the year to September housing credit was up 6.6% year-on-year,” says David Plank, Head of Australian Economics at ANZ.

“The annual growth rate has been steady since May, though it has accelerated marginally since this time last year and is still significantly outpacing income growth.”

So even with the slowdown in the housing market and increased scrutiny of borrowers, household leverage has still continued to increase, adding to financial stability risks should an unexpected economic shock occur.

Plank suggests that unless income growth accelerates substantially, or growth in housing credit slows, household leverage will likely increase further.

He doesn’t hold out much hope that an acceleration in income growth will be able to achieve this in isolation.

“We very much doubt that an acceleration of income growth will completely close the gap,” he says.

“For this to happen, we need to see a further slowing in the growth rate of housing debt. “We think it unlikely that the gap can be closed without additional policy action.”

While Plank doesn’t think the RBA or APRA will rush into tighter restrictions on housing lending anytime soon, noting that annual housing credit growth has slowed marginally since APRA changes were introduced earlier this year, he says that other measures will likely be required to slow or reduce household leverage.

And that list includes rate hikes.

“We think the RBA and APRA will wait to see how things unfold, especially with house price inflation continuing to slow,” he says.

“We are sceptical, however, that the gap between debt and income growth will close without more direct policy action.

“This may initially be in the form of further macro-prudential policy, but ultimately we think it will take somewhat higher interest rates, at the very least, to bring household debt growth in line with that of income.”

ANZ is forecasting that the RBA will lift interest rates twice in 2018 — once in May and again in the second half of the year — making it one of the more hawkish forecasters in the market at present.

“We think it will opt to raise rates around the middle of next year, so long as it is confident that inflation is not moving lower and the economy is on track to deliver a falling unemployment rate,” Plank says.

The question, he says, is how will the RBA balance its inflation and financial stability objectives?

Attempting to address financial stability risks while at the same time ensuring the fledgling economic recovery isn’t derailed before it is truly self-sustaining will not be an easy task for the RBA.

Indeed, one could easily argue that higher interest rates or tighter macroprudential measures to reduce household leverage could actually heighten financial instability risks.

Given the pressure on households from high levels of indebtedness, weak wage growth and increased energy costs, along with the slowdown in the housing markets that’s already underway, any further measures could place even further pressure on household balance sheets, creating additional headwinds for household consumption that already exist.

As the most important component in the Australian economy, weaker consumption levels would almost certainly lead to slower economic growth and softer labour market conditions.

For highly indebted households, a slowdown in the both the housing and labour markets — especially at the same time — would do little to mitigate financial stability risks.

One suspects it would be the exact opposite outcome, in fact.

You can see the dilemma facing Lowe, trying to solve one problem without creating an even larger one in response.

Given how influential the property market has become on the Australian economy, a policy misstep now could have significant ramifications, both now or in the future.