From The Mises Institute.

The boom brought about by the banks’ policy of extending credit must necessarily end sooner or later. Unless they are willing to let their policy completely destroy the monetary and credit system, the banks themselves must cut it short before the catastrophe occurs. The longer the period of credit expansion and the longer the banks delay in changing their policy, the worse will be the consequences of the malinvestments and of the inordinate speculation characterizing the boom; and as a result the longer will be the period of depression and the more uncertain the date of recovery and return to normal economic activity

Fed policy makers are of the view that if there is the need to tighten the interest rate stance the tightening should be gradual as to not destabilize the economy.

The gradual approach gives individuals plenty of time to adjust to the tighter monetary stance. This adjustment in turn will neutralize the possible harmful effect that such a tighter stance may have on the economy.

But is it possible by means of a gradual monetary policy to undo the damage inflicted to the economy by previous loose monetary policies? According to mainstream economic thinking, it would appear that this is the case.

But is it possible by means of a gradual monetary policy to undo the damage inflicted to the economy by previous loose monetary policies? According to mainstream economic thinking, it would appear that this is the case.

In his various writings, the champion of the monetarist school of thinking, Milton Friedman, has argued that there is a variable lag between changes in money supply and its effect on real output and prices. Friedman holds that in the short run changes in money supply will be followed by changes in real output. In the long run, according to Friedman, changes in money will only have an effect on prices.

It follows then that changes in money with respect to real economic activity tend to be neutral in the long run and non-neutral in the short run. Thus according to Friedman,

In the short-run, which may be as much as five or ten years, monetary changes affect primarily output. Over decades, on the other hand, the rate of monetary growth affects primarily prices.

According to Friedman, the effect of the change in money supply shows up first in output and hardly at all in prices. It is only after a longer time lag that changes in money start to have an effect on prices. This is the reason, according to Friedman, why in the short run money can grow the economy, while in the long run it has no effect on the real output.

According to Friedman, the main reason for the non-neutrality of money in the short run is the variability in the time lag between money and the economy. Consequently, he believes that if the central bank were to follow a constant money rate of growth rule this would eliminate fluctuations caused by variable changes in the money supply rate of growth. The constant money growth rule could also make money neutral in the short run and the only effect that money would have is on general prices.

Thus according to Friedman,

On the average, there is a close relation between changes in the quantity of money and the subsequent course of national income. But economic policy must deal with the individual case, not the average. In any case, there is much slippage. It is precisely this leeway, this looseness in the relation, this lack of mechanical one-to-one correspondence between changes in money and in income that is the primary reason why I have long favoured for the USA a quasi-automatic monetary policy under which the quantity of money would grow at a steady rate of 4 or 5 per cent per year, month-in, month-out.

In his Nobel lecture, Robert Lucas raised an issue with this. According to Lucas,

If everyone understands that prices will ultimately increase in proportion to the increase in money, what force stops this from happening right away?

Consequently, Lucas has suggested that the reason why money does generate a real effect in the short run is not so much due to the variability of monetary time lags but more bound up with whether money changes were anticipated or not. If monetary growth anticipated, then people will adjust to it rather quickly and there will not be any real effect on the economy. Only unanticipated monetary expansion can stimulate production.

Moreover, according to Lucas,

Unanticipated monetary expansions, on the other hand, can stimulate production as, symmetrically, unanticipated contractions can induce depression.

Both Friedman and Lucas are of the view, although for slightly different reasons, that it is desirable to make money neutral in order to avoid unstable and therefore unsustainable economic growth.

The current practice of Fed policy makers seems to incorporate the ideas of Friedman and Lucas into the so-called transparent monetary policy framework. This framework accepts Lucas’s view that anticipated monetary policy could lead to stable economic growth. This framework also accepts that a gradual change in monetary policy in the spirit of Friedman’s constant money growth rule could reinforce the transparency.

If unexpected monetary policies can cause real economic growth, what is wrong with this? Why not constantly surprise people and cause more real wealth?

Money, Expectations and Economic Growth

What is required for economic growth is a growing pool of real savings, which funds various individuals that are engaged in the build-up of capital goods. An increase in money, however, has nothing to do, as such, with this. On the contrary this increase only leads to consumption that is not supported by production of real wealth. Consequently, this leads to a weakening in the real pool of savings, which in turn undermines real economic growth. All that printing money can achieve is a redirection of real savings from wealth generating activities towards non-productive wealth consuming activities. So obviously, there cannot be any economic growth because of this redirection.

Now if unanticipated monetary growth undermines real economic growth via the dilution of the pool of real savings why is it then that one observes that rising money is associated with a rise in economic indicators like real GDP?

We suggest that all that we observe in reality is an increase in monetary spending — this is what GDP depicts. The more money that is printed, the higher GDP will be. So-called real GDP is merely nominal GDP deflated by a meaningless price index. Hence, so-called observed economic growth is just the reflection of monetary expansion and has nothing to do with real economic growth. Incidentally, real economic growth cannot be measured as such — it is not possible to establish a meaningful total by adding potatoes and tomatoes.

While unanticipated monetary growth cannot grow the economy, it definitely produces a real effect by undermining the pool of real savings and thereby weakening the real economy.

Likewise anticipated money growth cannot be harmless to the real economy. Even if the money rate of growth is fully anticipated there is always someone who gets it first. Consequently, also anticipated money growth rate will set in motion an exchange of nothing for something.

For instance, consider the individual who fully expects the future course of monetary policy. This individual now decides to borrow $1000 from a bank. The bank obliges and lends him the $1000, which the bank has created out of “thin air”. Now, since this money is unbacked by any previous production of real wealth it will set in motion an exchange of nothing for something, or a redirection of real savings from wealth generators towards the borrower of the newly created $1000. This redirection and hence real negative effect on the pool of savings cannot be prevented by an individuals’ correct expectation of monetary policies.

Even if the money is pumped in such a way that everybody gets it instantaneously, changes in the demand for money will vary. After all, every individual is different from other individuals. There will always be somebody who will spend the newly received money before somebody else. This of course will lead to the redirection of real wealth to the first spender from the last spender.

We can thus conclude that regardless of expectations, loose monetary policy will always undermine the foundations of the real economy while tight monetary policy will work to arrest this process. Hence monetary policy can never be neutral.

Can a Gradual Tightening Prevent an Economic Bust?

Since monetary growth, whether expected or unexpected, gives rise to the redirection of real savings it means that any monetary tightening slows down this redirection. Various economic activities, which sprang-up on the back of strong monetary pumping, because of a tighter monetary stance get now less real funding. This in turn means that these activities are given less support and run the risk of being liquidated. It is the liquidation of these activities what an economic bust is all about.

Obviously, then, the tighter monetary stance by the Fed must put pressure on various false activities, or various artificial forms of life. Hence, the tighter the Fed gets the slower the pace of redirection of real savings will be, which in turn means that more liquidation of various false activities will take place. In the words of Ludwig von Mises,

The boom brought about by the banks’ policy of extending credit must necessarily end sooner or later. Unless they are willing to let their policy completely destroy the monetary and credit system, the banks themselves must cut it short before the catastrophe occurs. The longer the period of credit expansion and the longer the banks delay in changing their policy, the worse will be the consequences of the malinvestments and of the inordinate speculation characterizing the boom; and as a result the longer will be the period of depression and the more uncertain the date of recovery and return to normal economic activity.

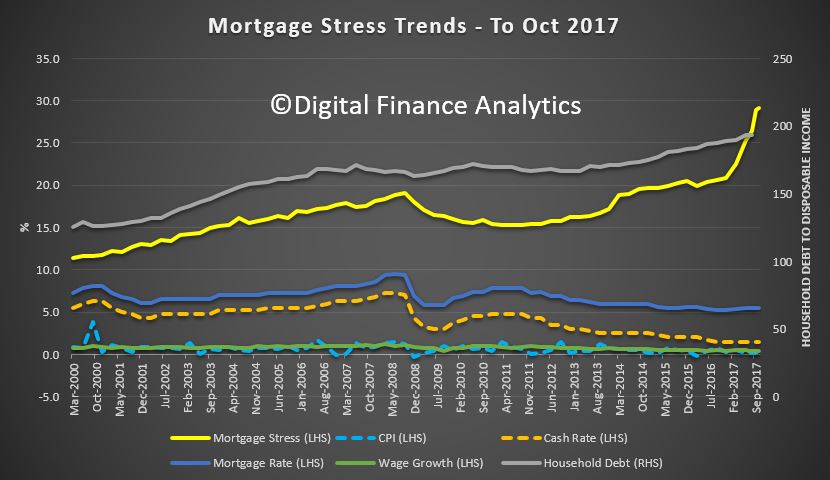

Consequently, the view that the Fed can lift interest rates without any disruption doesn’t hold water. Obviously if the pool of real savings is still expanding then this may mitigate the severity of the bust. However, given the reckless monetary policies of the US central bank it is quite likely that the US economy may already has a stagnant or perhaps a declining pool of real savings. This in turn runs the risk of the US economy falling into a severe economic slump.

We can thus conclude that the popular view that gradual transparent monetary policies will allow the Fed to tighten its stance without any disruptions is based on erroneous ideas. There is no such thing as a “shock-free” monetary policy any more than a monetary expansion can ever be truly neutral to the market.

Regardless of policy transparency once a tighter monetary stance is introduced, it sets in motion an economic bust. The severity of the bust is conditioned by the length and magnitude of the previous loose monetary stance and the state of the pool of real savings.

1. Milton Friedman The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory. Occasional Paper 33, Institute of Economic Affairs for the Wincott Foundation. London: Tonbridge, 1970.

Milton Friedman The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory

Robert E. Lucas, Jr Nobel Lecture:Monetary Neutrality, Journal of Political Economy, 1996, vol. 104,no. 4

Ibid.

Ludwig von Mises, The “Austrian” Theory of the Trade Cycle. The Ludwig von Mises Institute 1983.

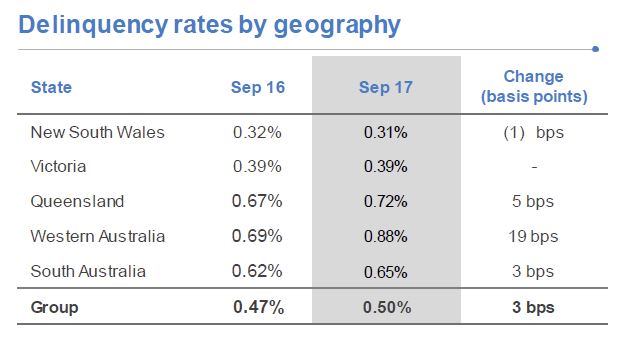

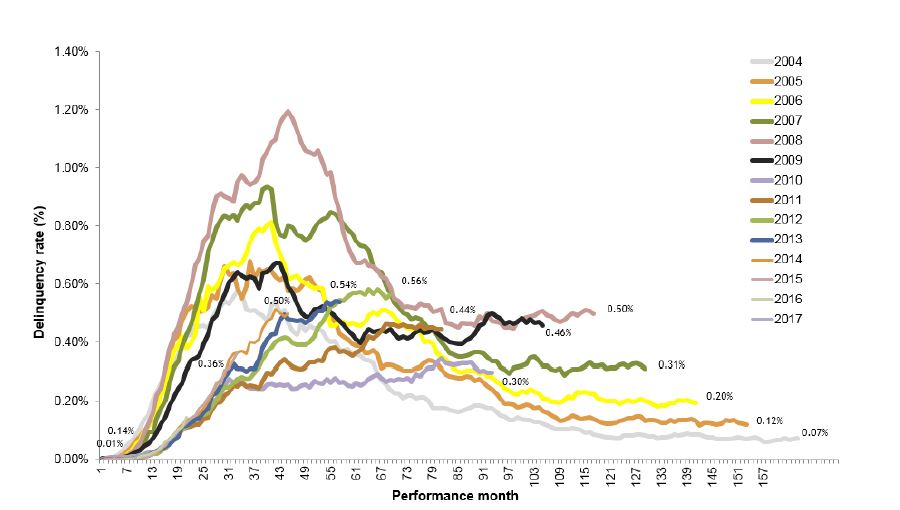

The total portfolio of delinquencies rose 4.4% to 7,146, and the loss rate overall was 3 basis points. The regional variations are stark.

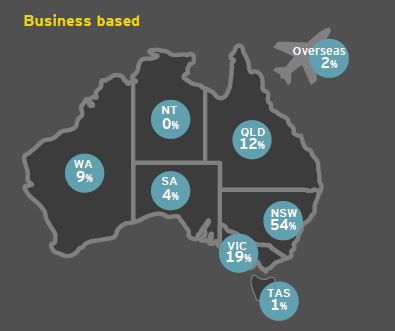

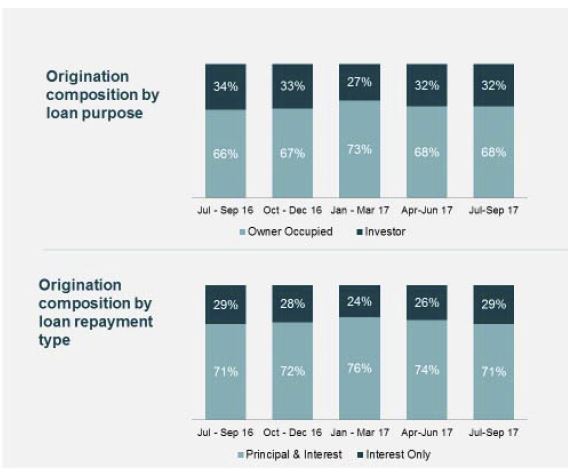

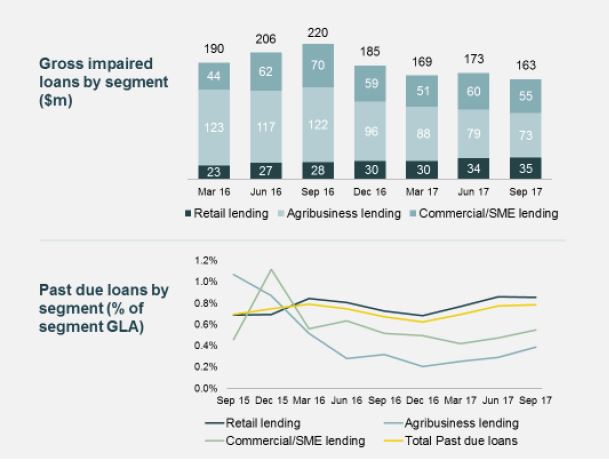

The total portfolio of delinquencies rose 4.4% to 7,146, and the loss rate overall was 3 basis points. The regional variations are stark. The loss ratio however fell, 8.3 pts to 37%, thanks to (DFA suggests) equity linked to rising home prices. New South Wales and Victoria continue to perform strongly. However, the performance in Queensland and Western Australia remains challenging and delinquencies are elevated due to the slowdown in those regional and metropolitan areas that have previously benefited from the growth in the resources sector.

The loss ratio however fell, 8.3 pts to 37%, thanks to (DFA suggests) equity linked to rising home prices. New South Wales and Victoria continue to perform strongly. However, the performance in Queensland and Western Australia remains challenging and delinquencies are elevated due to the slowdown in those regional and metropolitan areas that have previously benefited from the growth in the resources sector. The 2008 book year was affected by the economic downturn experienced across Australia and heightened stress among self-employed borrowers, particularly in Queensland, which was exacerbated by the floods 2011. Post PostPost-GFC book years seasoning at lower levels as a result of credit tightening. Underperformance for 2012-14 books have been predominantly driven by resource reliant states of QLD and WA following the mining sector downturn however has started to show signs of stabilising over recent months.

The 2008 book year was affected by the economic downturn experienced across Australia and heightened stress among self-employed borrowers, particularly in Queensland, which was exacerbated by the floods 2011. Post PostPost-GFC book years seasoning at lower levels as a result of credit tightening. Underperformance for 2012-14 books have been predominantly driven by resource reliant states of QLD and WA following the mining sector downturn however has started to show signs of stabilising over recent months. There is considerable variation in economic activity across the country with continued growth in New South Wales and Victoria offset by weaker activity in Queensland and, in particular, Western Australia.

There is considerable variation in economic activity across the country with continued growth in New South Wales and Victoria offset by weaker activity in Queensland and, in particular, Western Australia.