In a speech by FED Chair Yellen, at the Group of 30 International Banking Seminar, she discussed the problem of low inflation, and admitted that their understanding of why it remains so low is imperfect and low inflation may persist. Perhaps the labour market is really softer than reported; perhaps long term trends will remain lower; perhaps technological and sectorial changes may be impacting. Despite this, she expects the FED rate to rise in the months ahead.

The biggest surprise in the U.S. economy this year has been inflation. Earlier this year, the 12-month change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) reached 2 percent, and core PCE inflation reached 1.9 percent. These readings seemed consistent with the view that inflation had been held down by both the sizable fall in oil prices and the appreciation of the dollar starting around mid-2014, and that these influences have diminished significantly by this year. Accordingly, inflation seemed well on its way to the FOMC’s 2 percent inflation objective on a sustainable basis.

Inflation readings over the past several months have been surprisingly soft, however, and the 12-month change in core PCE prices has fallen to 1.3 percent. The recent softness seems to have been exaggerated by what look like one-off reductions in some categories of prices, especially a large decline in quality-adjusted prices for wireless telephone services. More generally, it is common to see movements in inflation of a few tenths of a percentage point that are hard to explain, and such “surprises” should not really be surprising. My best guess is that these soft readings will not persist, and with the ongoing strengthening of labor markets, I expect inflation to move higher next year. Most of my colleagues on the FOMC agree. In the latest Summary of Economic Projections, my colleagues and I project inflation to move higher next year and to reach 2 percent by 2019.

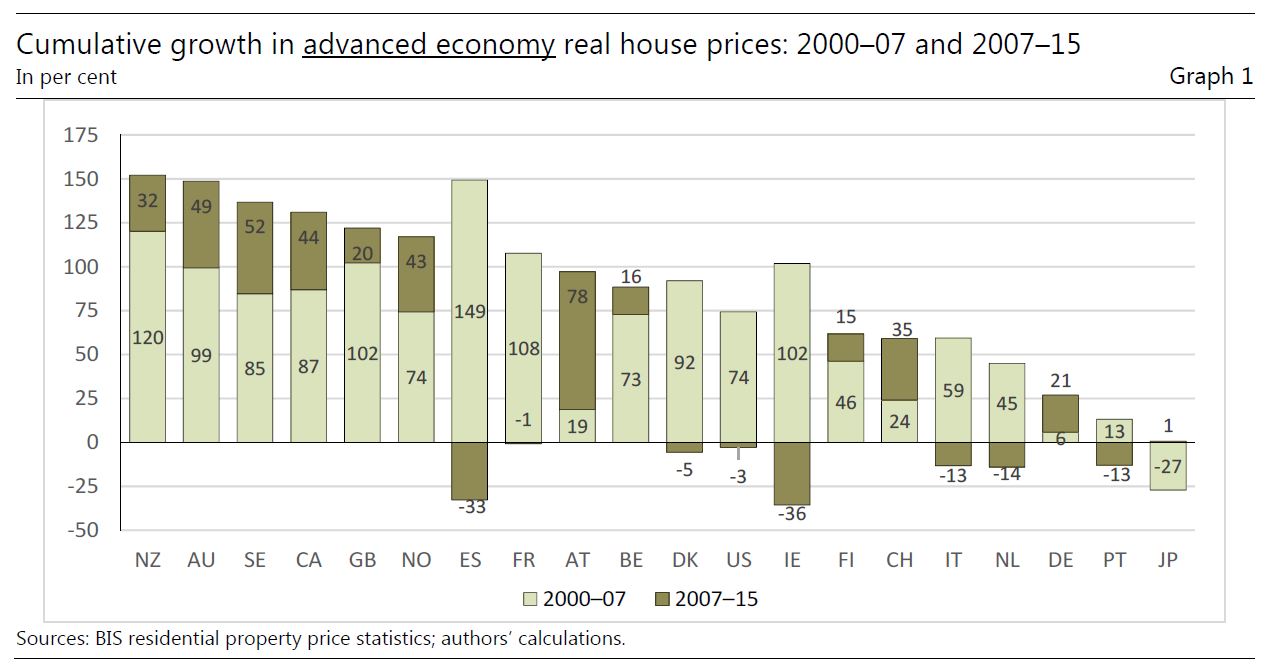

To be sure, our understanding of the forces that drive inflation is imperfect, and we recognize that this year’s low inflation could reflect something more persistent than is reflected in our baseline projections. The fact that a number of other advanced economies are also experiencing persistently low inflation understandably adds to the sense among many analysts that something more structural may be going on. Let me mention a few possibilities of more fundamental influences.

First, given that estimates of the natural rate of unemployment are so uncertain, it is possible that there is more slack in U.S. labor markets than is commonly recognized, which may be true for some other advanced economies as well. If so, some further tightening in the labor market might be needed to lift inflation back to 2 percent.

Second, some measures of longer-term inflation expectations have edged lower over the past few years in several major economies, and it remains an open question whether these measures might be reflecting a true decline in expectations that is broad enough to be affecting actual inflation outcomes.

Third, our framework for understanding inflation dynamics could be misspecified in some way. For example, global developments–perhaps technological in nature, such as the tremendous growth of online shopping–could be helping to hold down inflation in a persistent way in many countries. Or there could be sector-specific developments–such as the subdued rise in medical prices in the United States in recent years–that are not typically included in aggregate inflation equations but which have contributed to lower inflation. Such global and sectoral developments could continue to be important restraining influences on inflation. Of course, there are also risks that could unexpectedly boost inflation more rapidly than expected, such as resource utilization having a stronger influence when the economy is running closer to full capacity.

In this economic environment, with ongoing improvements in labor market conditions and softness in inflation that is expected to be temporary, the FOMC has continued its policy of gradual policy normalization. As the Committee announced after our September meeting, we are initiating our balance sheet normalization program this month. That program, which was described in the June Addendum to the Policy Normalization Principles and Plans, will gradually scale back our reinvestments of proceeds from maturing Treasury securities and principal payments from agency securities. As a result, our balance sheet will decline gradually and predictably.2 By limiting the volume of securities that private investors will have to absorb as we reduce our holdings, the caps should guard against outsized moves in interest rates and other potential market strains.

Changing the target range for the federal funds rate is our primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy. Our balance sheet is not intended to be an active tool for monetary policy in normal times. We therefore do not plan on making adjustments to our balance sheet normalization program. But, of course, as we stated in June, the Committee would be prepared to resume reinvestments if a material deterioration in the economic outlook were to warrant a sizable reduction in the federal funds rate.

Also at our September meeting, the Committee decided to maintain its target for the federal funds rate. We continue to expect that the ongoing strength of the economy will warrant gradual increases in that rate to sustain a healthy labor market and stabilize inflation around our 2 percent longer-run objective. That expectation is based on our view that the federal funds rate remains somewhat below its neutral level–that is, the level that is neither expansionary nor contractionary and keeps the economy operating on an even keel. The neutral rate currently appears to be quite low by historical standards, implying that the federal funds rate would not have to rise much further to get to a neutral policy stance. But we expect the neutral level of the federal funds rate to rise somewhat over time, and, as a result, additional gradual rate hikes are likely to be appropriate over the next few years to sustain the economic expansion. Indeed, FOMC participants have built such a gradual path of rate hikes into their projections for the next couple of years.