Sydney’s deflating house prices have dragged the property market down across the entire country, in the most conclusive sign yet that the boom is over, figures from CoreLogic have revealed.

For the month of October – traditionally a bumper month for property sales – average house prices across Australia’s capital cities posted no growth at all.

Sydney house prices fell by 0.5 per cent, bringing quarterly losses to 0.6 per cent.

Prices in Canberra and Darwin also fell (by 0.1 per cent and 1.6 per cent respectively), while Adelaide and Perth each posted zero growth.

Of the capital cities, only Melbourne, Brisbane and Hobart saw property prices increase, at 0.5 per cent, 0.2 per cent and 0.9 per cent respectively.

Perth’s flat growth was also an improvement on a long period of falling prices.

The poor results will be a disappointment to sellers who assumed a spring sale would optimise the value of their property.

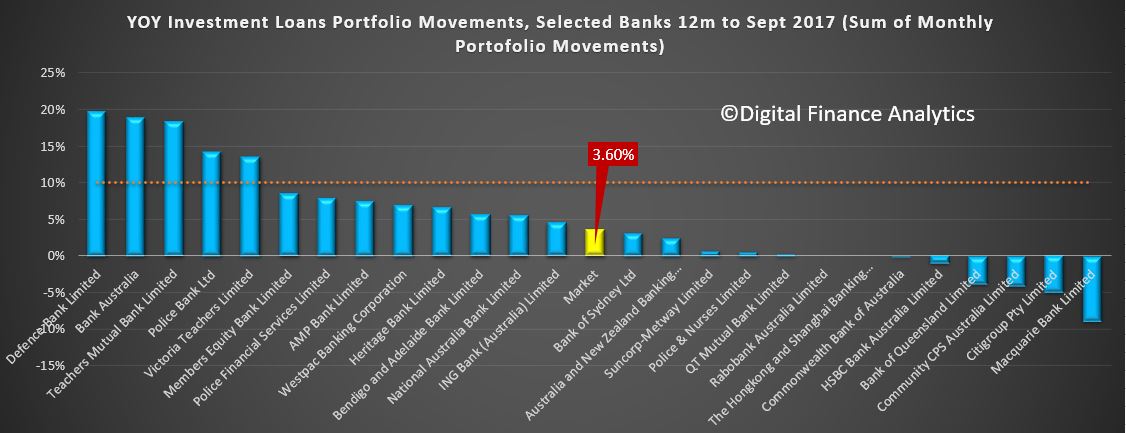

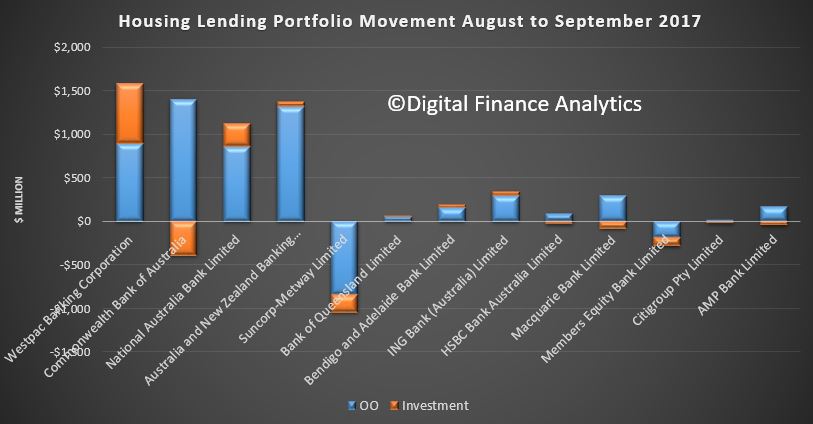

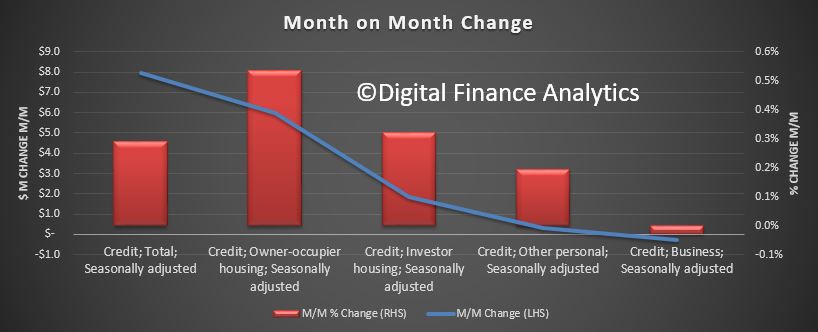

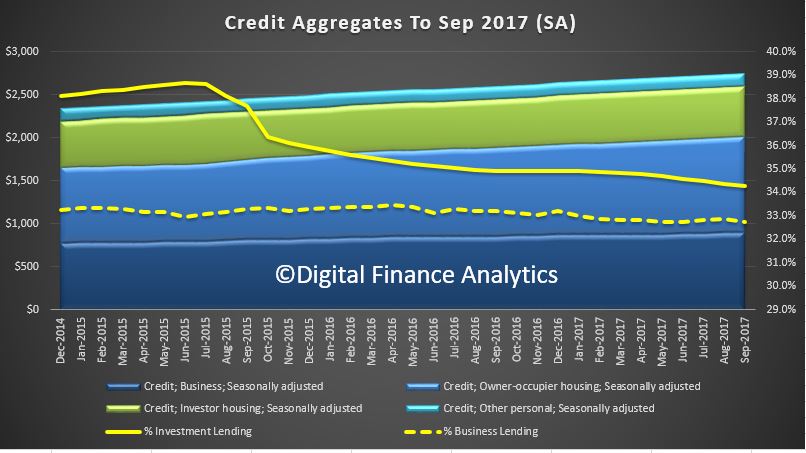

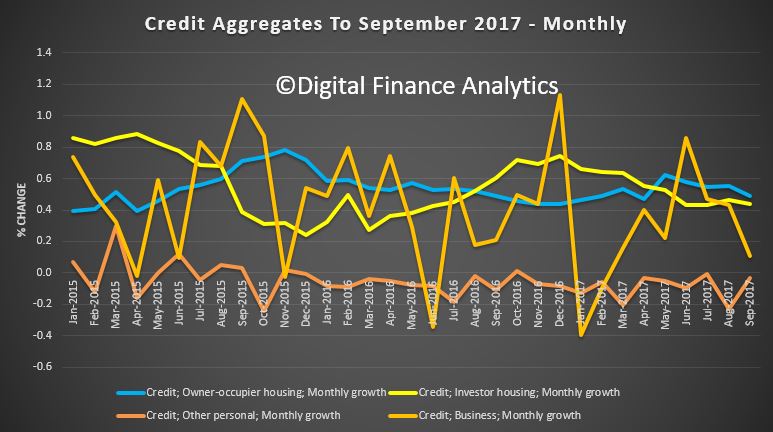

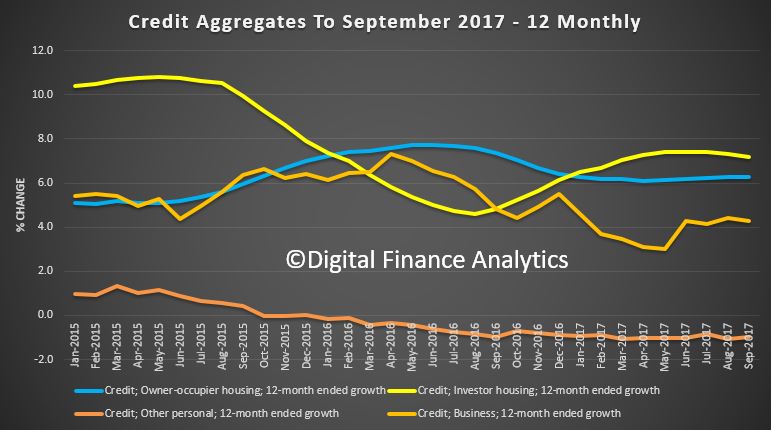

CoreLogic’s head of research Tim Lawless put the low growth down, primarily, to tighter restrictions on lending.

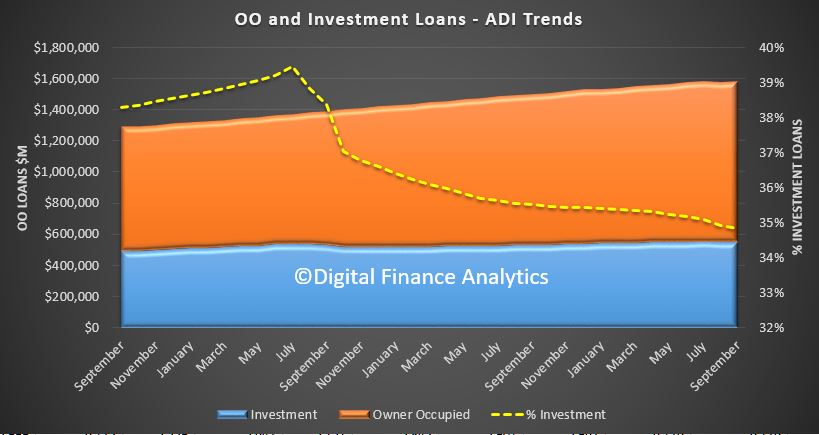

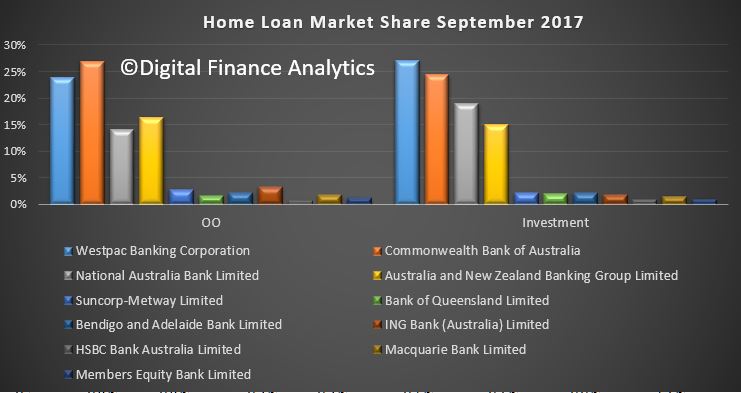

“Lenders have tightened their servicing tests and reduced their appetite for riskier loans, including those on higher loan-to-valuation ratios or higher loan-to-income multiples,” he said.

He added that more expensive rates on interest-only loans were acting as a disincentive for property investors, particularly those that offered low rental yield.

Commenting on the NSW capital’s poor results, Mr Lawless said: “Seeing Sydney listed alongside Perth and Darwin, where dwelling values have been falling since 2014, is a significant turn of events.”

However, despite the recent depreciation, house prices in Sydney are still 7.7 per cent higher than they were a year ago.

Turning to Melbourne, Mr Lawless put the city’s continued growth down to “record-breaking migration rate”, which he said was creating “unprecedented housing demand”.

Units v Houses

In most capital cities, houses continued to see higher capital growth than units, due to overdevelopment of the latter. A notable exception to this was Sydney.

Over the year, unit values in Sydney grew by 7.9 per cent, compared to 7.7 per cent for houses.

“While Sydney is seeing a large number of new units added to the market, it seems that high levels of investment activity and strained affordability is helping to drive a better performance across this sector,” Mr Lawless.

The report found that rental yields, while they had grown 2.8 per cent over the year, were still extremely low when compared to house prices – which have on average risen 6.6 per cent over the year.

Sydney and Darwin were exceptions to this.

“If the Sydney market continues to see values slip lower while rents gradually rise, yields will repair, however a recovery in rental returns is likely to be a slow process,” Mr Lawless said.

Chinese money dries up

While CoreLogic put the flat growth down to tougher mortgage lending restrictions, a report by Credit Suisse offered a different explanation.

According to the ABC, the report found Chinese capital flows into Australia had fallen in recent months, and this was having a pronounced effect on the domestic property market.

“Over the past few months, the Sydney housing market has not only cooled down, but has arguably turned cold,” ABC quoted Credit Suisse as saying.

“Over the past year, Chinese capital flows have fallen considerably, in part reflecting the impact of stricter capital controls.

“This fall foreshadows weakness in NSW housing demand in the year ahead.”

This, Credit Suisse argued, could see the Reserve Bank forced to cut interest rates even further. Currently the cash rate sits at a record low of 1.5 per cent.