If you needed A$2,000 in a hurry where would you get it? 70% of those we surveyed said they would ask friends or family, although almost half said that it’s very or fairly unlikely that their social connections could help.

This is just one of the takeaways from our new report, funded by NAB, that shows financial resilience is declining in Australia. Large numbers of Australians are struggling to meet expenses, pay bills and manage or recover from financial shocks despite two decades of GDP growth, declining income inequality and increasing financial capability.

And while more adults in Australia are reporting regular social contact, and fewer are reporting needing community or government support, the number of Australians needing support but not receiving it has increased from 3.2% to 5.3%.

The problem is especially acute for those on low incomes. A recent report found most low-income households are unable to afford a minimum and healthy standard of living, with their incomes falling short by between A$9 and A$89 a week.

In this week’s Household Expenditure Survey, the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that two in every five households are experiencing at least one indicator of financial stress. In households with incomes in the bottom 40%, this ratio increases to one in two.

People on the lowest incomes are:

- 12 times more likely to be unable to raise A$2,000 in a week for something important

- Five times more likely to be unable to pay a utility bill on time

- Ten times more likely to be unable to heat their homes than the highest income households.

The lowest income households are also more likely to be socially isolated than the highest income group. For example, they were at least ten times more likely to be unable to afford a special meal once a week or a night out once a month.

As you can see in the above graphic, the proportion of Australian adults who are financially secure has decreased significantly between 2015 and 2016, from 35.7% to 31.2%. One in eight Australians (12.6%) now experience severe or high financial stress, up from 11.1%.

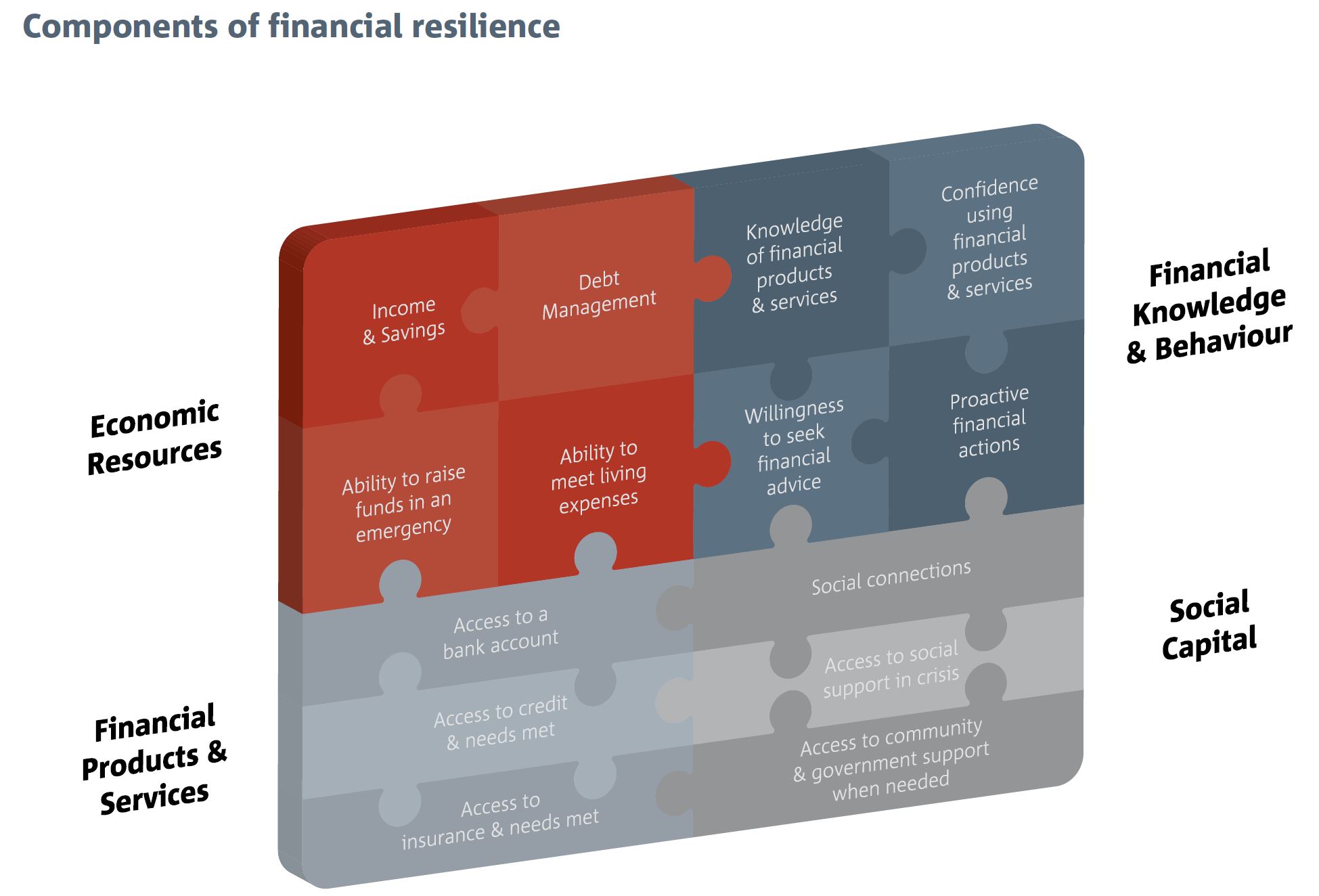

In practical terms financial stress may mean a combination of limited or no savings; difficulties meeting everyday living expenses, managing debts and raising funds in an emergency; no direct access to a bank account; no access to appropriate and affordable credit and/or low levels of social support.

When you dig deeper into the data you see this is not a problem of behaviour or financial literacy. The decline in financial resilience has occurred despite a significant improvement in the proportion of people with moderate to high levels of financial knowledge and behaviour (from 50% to 55%).

This includes a knowledge of, and confidence using, financial products and services. And a willingness to seek financial advice and engage in proactive behaviours like saving, budgeting and paying more than required on debts.

This leads to the conclusion that the cause of the decrease in financial resilience is due to a decline in external resources. This means people having enough money to meet living expenses and manage debts, and having access to a bank account, appropriate credit, insurance and being able to access social and community supports when needed.

We can see this by looking at data on savings.

More Australians are saving (up to 60.2% in 2016 from 56.4%). However, as you can see in the chart below, the total amount of savings has declined. Only one in two people had three months or more of income saved (a drop from 51.9% in 2015 to 49.5% in 2016). And people with savings of a month or less increased from 27.3% to 31.6%.

More Australians are budgeting, too. With 51.6% following a budget in the latest survey as compared to 49.1% in 2015.

The data also shows us that an inability to access appropriate financial products and services affects a large number of Australians. This was mainly driven by increases in the number of people who only had indirect access to a bank account (from 1.2% in 2015 to 2.7% in 2016) and increases in the number of people who had no access to appropriate credit (20.2% in 2015 compared to 25.6% in 2016).

Appropriate and affordable credit is important to assist people who cannot draw on savings when they experience financial shocks, such as the sudden need to replace a washing machine or fridge, or to fix a car needed to get to work.

As we can see, stories of economic growth and declining income inequality aren’t capturing the whole picture. It is important that we don’t overlook the large number of people and households in Australia who are experiencing high levels of financial stress, who are struggling to pay the bills and meet basic living expenses.

Our research shows that large numbers of people and households are not prepared, or adequately supported, should a financial shock (such as an increase in interest rates or a recession) materialise.

While most people have strong social support; more appropriate, affordable and accessible financial support from the government, communities and financial institutions is required. This is along with appropriate mechanisms to help identify people most at risk and to cross refer where required.

Authors: Kristy Muir, Professor of Social Policy / Research Director, Centre for Social Impact, UNSW; Axelle Marjolin, Researcher at the Centre for Social Impact, UNSW