Domestic Economic Conditions

Members commenced their discussion of the domestic economy by noting that the June quarter inflation data had been in line with the Bank’s expectations and provided further confirmation that inflation had increased since 2016. Underlying inflation was ½ per cent in the June quarter and headline inflation was only slightly lower. Both Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation and measures of underlying inflation were running at a little under 2 per cent in year-ended terms.

Non-tradables inflation had reached its highest year-ended rate in two years in the June quarter, boosted by rises in tobacco excise and utilities prices. Market services inflation had increased since 2016, but remained low; around half of total costs in the market services sector are labour costs, and these had been subdued over recent years. Inflation in the costs of constructing a new dwelling had also increased over the prior year in all capital cities other than Perth and Adelaide. In contrast, rents had been increasing at a below-average pace in Sydney and Melbourne, had been falling in Perth and had been broadly stable in most other capital cities.

The prices of tradable consumer durable items had declined over the year, partly reflecting the appreciation of the exchange rate and heightened competition from foreign retailers. Inflation in food prices (excluding fruit and vegetables) had been running at low rates for several years. Supply disruptions from Cyclone Debbie had had relatively little net effect on fruit and vegetables prices in the June quarter. Fuel prices had fallen in the quarter, but had contributed 0.2 percentage points to headline inflation over the year.

Members noted that the Australian Bureau of Statistics intends to update the weights in the CPI in the December quarter 2017 CPI release, to reflect changes in consumers’ spending behaviour over recent years. This was expected to lead to lower reported CPI inflation because the weights of items whose prices had fallen were likely to be higher, whereas the weights of items whose prices had risen were likely to be lower.

In their discussion of the outlook for the domestic economy, members noted that the Bank’s forecasts for output growth and inflation were largely unchanged from three months earlier. They noted that the forecasts were conditioned on the assumption of no change in the Australian dollar exchange rate during the forecast period, which extends to the end of 2019, and that this assumption was one source of uncertainty.

The available data on activity suggested that GDP growth had increased in the June quarter, following weaker-than-expected growth in the March quarter. Output growth was expected to reach around 3 per cent in year-ended terms during 2018 and 2019, which was a little higher than estimates of potential growth. The recent data had indicated that consumption growth had increased in the June quarter. The value of retail sales had risen strongly in April and May, and the increases had been broadly based both nationally and across spending categories. Beyond the June quarter, rising employment and stronger household income growth were expected to support consumption growth, which was forecast to be a little above its average of recent years.

Dwelling investment was expected to recover from the weakness in the March quarter, which was partly the result of wet weather in New South Wales, and remain at a high level over the following year or so, sustained by the large pipeline of residential building work already approved or under way. The number of new residential building approvals had stepped down since 2016 and members noted that, if approvals remained at current levels, construction activity could also begin to decline.

The established housing markets in Sydney and Melbourne had remained the strongest in the country, although conditions had eased since late 2016. Housing prices in Perth had declined a little further, while apartment price growth in Brisbane had been weak.

Turning to the business sector, members noted that activity in the mining sector was expected to be supported in the June quarter by stronger resource export volumes. Coking coal exports had returned to pre-cyclone levels in May, and liquefied natural gas exports had continued to increase. The decline in mining investment was expected to run its course in the following year or so and thereafter no longer be a drag on growth. Resource exports were expected to make a significant contribution to GDP growth over the forecast period.

Investment by non-mining businesses was expected to pick up later in the forecast period in response to stronger growth in demand. Businesses had continued to report above-average business conditions and members noted that many of the conditions that might typically be associated with stronger growth in investment were in place. Some indicators of non-mining investment, including recent strength in sales of commercial motor vehicles and the higher investment intentions recorded in the NAB survey, had been more positive in the period leading up to the meeting. The increase in the level of non-residential building approvals had also signalled a more positive outlook for private non-residential construction, although the pipeline of work to be done was at low levels. The pipeline of public infrastructure activity had increased over the previous few years, to be at its highest share of GDP since the mid 1980s. The expected increase in expenditure on public infrastructure had been reported as flowing into the order books of firms in the private sector.

Members observed that recent data had suggested further improvement in the labour market. Employment had increased in every state since the start of 2017, including solid growth in the mining-exposed states. This provided further evidence that the drag on economic activity from earlier declines in the terms of trade and falling mining investment were running their course. Over this period, around 165,000 full-time jobs had been created, labour force participation had risen and average hours worked had increased.

The unemployment rate had been little changed in June at 5.6 per cent and underemployment had edged lower over prior months. Indicators of labour demand had pointed to further employment growth and little change in the unemployment rate over coming quarters. By the end of the forecast period, the unemployment rate was expected to be just below 5½ per cent, slightly lower than forecast in May but still implying a degree of spare capacity in the labour market. Members observed that the recent improvement in labour market conditions and the increase in award wages should help support household incomes and thus spending. Some upside risk to spending could be envisaged if employment were to be higher than forecast. On the other hand, expectations of ongoing low wage growth could weigh on consumption growth. Spending could also be constrained by elevated levels of household debt, especially if housing market conditions were to weaken.

More broadly, members noted there was some uncertainty about the effect any decline in spare capacity in the labour market would have on wage and price inflation. Information from liaison indicated that some employers were finding it harder to attract workers with particular skills. If this were to broaden, wage growth could increase more quickly than forecast, which would see inflationary pressures also emerge more quickly. However, wage and price inflation had not increased by as much as expected in other economies around the world that are already close to full employment, which raised the possibility that low inflation in Australia might also persist longer than forecast.

Turning to the inflation forecast, members noted that underlying inflation was expected to be close to 2 per cent in the second half of 2017 and to edge higher over the subsequent two years. Most of the difference between headline and underlying inflation over the forecast period could be accounted for by further increases in tobacco excise and utilities prices. Retail electricity prices were expected to increase sharply in the September quarter, following the increases in retail prices in New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia on 1 July, and the March quarter 2018, when similar increases were expected in Victoria. Members acknowledged that the second-round effects of higher utilities prices on retail prices through business costs were uncertain, partly because it was unclear when utilities contracts for businesses would be subject to renewal. Members also observed that energy is a relatively low share of costs for most businesses, although it is higher for some businesses that compete in international markets.

The inflation forecast partly reflected an expectation of a modest increase in wage growth as labour market conditions tightened further and the drag on activity and incomes from falls in mining investment and the terms of trade diminished. Working in the opposite direction were the effects of additional competition in the retail industry, the dampening effect of expanding housing supply on growth in rents, and the recent exchange rate appreciation. Headline inflation had been revised a little higher in the updated forecasts, mostly reflecting the prospect of faster growth in utilities prices, and was expected to be between 2 and 3 per cent over much of the forecast period.

International Economic Conditions

Members commenced their discussion of the global economy by noting that economic conditions had strengthened over the prior year and the improvement had broadened beyond international trade. In particular, growth in business investment had picked up in several advanced and emerging economies, including the United States, Canada, Japan and a number of economies in east Asia. Consumption growth had been resilient. Recent GDP data had generally confirmed earlier expectations and, accordingly, the forecast for global growth had been little changed since that published in the May Statement on Monetary Policy. A gradual increase in global inflationary pressures over the subsequent couple of years had seemed likely, as spare capacity in many advanced economies was expected to be absorbed, resulting in higher wage growth. However, as members noted, even though labour market conditions had already tightened in some advanced economies, wage growth and core inflation had remained subdued.

Growth in GDP in China had been a little stronger than expected in the June quarter, supported by accommodative financial conditions and expansionary fiscal policy. The strengthening in conditions in the industrial sector over recent months had been broadly based; construction activity had been resilient, although housing market policies introduced in some cities over the preceding year had been effective in lowering overall housing price inflation. Demand for both consumer goods and Chinese exports had picked up. The strength in manufacturing and construction activity had contributed to higher demand for steel. As a result, imports of iron ore, including from Australia, had trended higher and prices for iron ore and coking coal had increased since the previous meeting. The outlook for Australia’s thermal coal exports had not benefited to the same extent, partly because there had been an increase in domestic Chinese production. The forecast for Australia’s terms of trade had been revised up a little since May, but still implied a decline from their recent peak.

Growth in China was expected to ease in 2018 and 2019 because of structural factors such as a declining working-age population, as well as policies to address financial risks. Members noted that the outlook for the Chinese economy remained a significant source of uncertainty. In particular, it was unclear how the authorities would negotiate the difficult trade-off between growth and the build-up of leverage in the Chinese economy. To address risks in the shadow banking sector, the authorities had recently sought to improve coordination among financial regulators and had announced tighter regulatory measures. Members noted that such measures could be difficult to calibrate and that, as a result, financial conditions might tighten by more than expected.

GDP growth in the rest of east Asia looked to have been around estimates of potential in the first half of 2017, supported by accommodative policies as well as the increase in global trade growth. Members noted that many economies in this region were deeply integrated into global supply chains, particularly for semiconductors and other electronics. There had also been signs of a recovery in retail sales and a sharp increase in consumer confidence in South Korea, the largest economy in the region.

In the three largest advanced economies, investment growth had picked up and employment growth had supported growth in household incomes and consumption. GDP growth had picked up in the June quarter in the United States and had been above potential rates for some time in the euro area and Japan, which had experienced sizeable increases in exports as global economic conditions had improved. GDP growth in all three major advanced economies was expected to remain above estimates of potential growth over the forecast period. Unemployment rates had declined to low levels in all three economies and in the United States and Japan were below levels associated with full employment.

Financial Markets

Members noted that over recent months most attention in international financial markets had been on changes in expectations regarding monetary policy. In a number of advanced economies, monetary policy was expected to be somewhat less accommodative than previously anticipated.

At its June meeting, the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) increased its policy rate and outlined plans for a gradual and predictable reduction in the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. More recently, the FOMC had indicated that the balance sheet reduction would be likely to begin relatively soon. Financial market participants continued to expect further increases in the US federal funds rate to occur more slowly than implied by the median projections of FOMC participants. At its July meeting, the European Central Bank had emphasised that monetary policy needed to remain very accommodative, but had also indicated that it will consider whether to reduce the pace of asset purchases at one of its forthcoming meetings. In July, the Bank of Canada raised its policy rate for the first time in seven years and financial market participants expected further increases. Central banks in several other advanced economies had also adjusted their communication over recent months so as to remove earlier biases towards easier monetary policy.

Long-term government bond yields had responded to the changes in expectations for the stance of monetary policy, with yields in most major financial markets, as well as in Australia, having risen from their levels in early June. Members noted, however, that yields remained at low levels. In Japan, yields on 10-year government bonds had remained around zero during 2017, consistent with the Bank of Japan’s policy of yield curve control.

Members observed that financial market conditions remained very favourable. Corporate financing conditions had continued to improve, with the increase in equity prices and decline in corporate bond spreads having continued over 2017 in the United States and the euro area.

In China, financial market conditions also remained accommodative, but had tightened since the end of 2016 as the authorities had instituted a range of measures to reduce leverage in financial markets. Bond yields had increased markedly since late 2016, despite a slight retracement in recent months, and corporate bond issuance had slowed following strong growth over the preceding several years. Members observed that credit availability to households and businesses had been relatively unaffected by the regulatory measures. The renminbi exchange rate had appreciated against the US dollar since the beginning of 2017, but had depreciated in trade-weighted terms. The Chinese authorities had increased their scrutiny of capital flows, resulting in a decline in net capital outflows, and the value of the People’s Bank of China’s foreign currency reserves had stabilised.

Members noted that there had been a broadly based depreciation of the US dollar over 2017, including against the Australian dollar. The appreciation of the Australian dollar over the previous two months had resulted in it returning to 2015 levels in US dollar terms and to the levels of late 2014 on a trade-weighted basis.

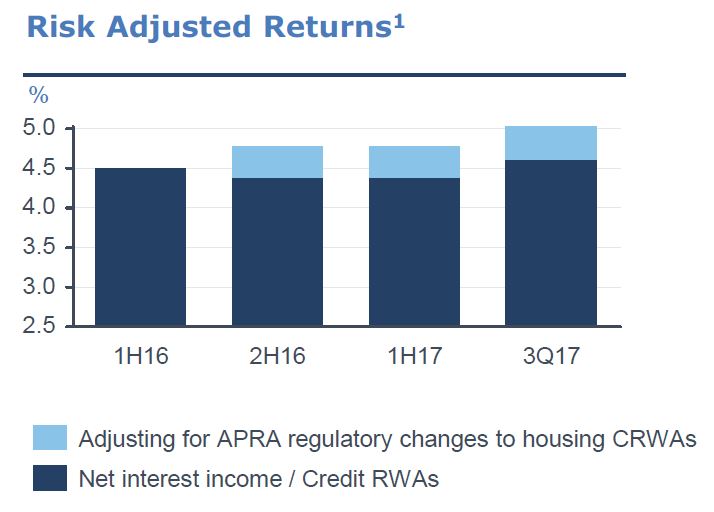

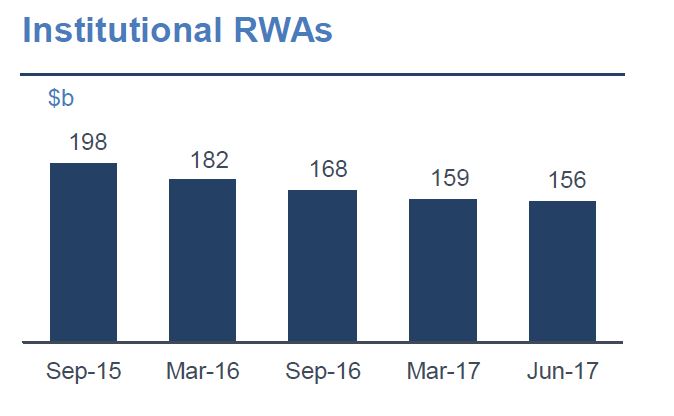

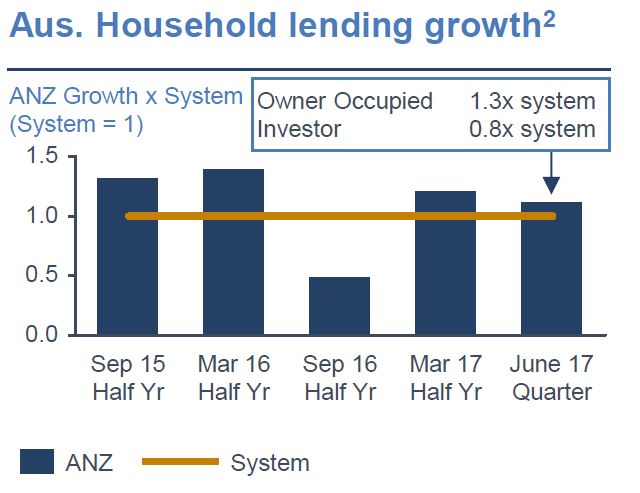

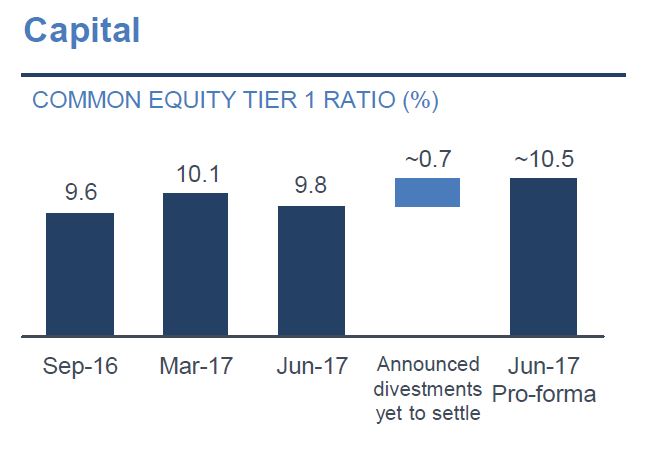

In Australia, housing credit growth had been steady over the first half of 2017, as a decline in growth in housing credit extended to investors had been offset by a slight increase in growth in housing credit to owner-occupiers. Members discussed the relative increases in housing lending rates to investors compared with owner-occupiers and for interest-only loans compared with principal-and-interest loans. Overall, the average actual interest rate paid on all outstanding housing loans was estimated to have increased slightly since late 2016. Housing loan approvals to investors had declined in recent months, which pointed to some easing in growth in housing credit to investors. The share of interest-only housing loans in total loan approvals appeared to have declined noticeably in the June quarter in response to recent measures introduced by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) to improve lending standards. Moreover, there was evidence of some switching of existing interest-only loans to principal-and-interest loans.

Australian share prices had been broadly steady in recent months. Over July, bank share prices had retraced some of their earlier decline, in line with a rise in bank share prices globally and following APRA’s announcement of additional capital requirements for the banking sector, which were only slightly higher than banks’ current actual capital ratios. The major banks had been issuing increasingly longer-dated bonds, including two large US-denominated 30-year bond issues in July. Members noted that longer-dated bonds are favoured under the Net Stable Funding Ratio requirement, which will come into effect in 2018. Members also noted that Australian issuance of residential mortgage-backed securities had continued at the relatively strong pace seen since late 2016.

Financial market pricing had continued to suggest that the cash rate was expected to remain unchanged over the remainder of 2017, with some expectation of an increase in the cash rate by mid 2018.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

In considering the stance of monetary policy, members noted that the improvement in global economic conditions had continued, particularly in China and the euro area. Demand growth from the Chinese industrial sector had been stronger than expected and had contributed to higher commodity prices. Labour markets had continued to tighten in a number of economies, but inflation had generally remained subdued. There had been a broadly based depreciation of the US dollar. Consistent with that, a number of currencies were close to their highs of the previous few years against the US dollar, including the euro and the Canadian dollar. The Australian dollar also had risen to levels last seen in 2015.

Domestically, the outlook was little changed. The forecast was for GDP growth to increase to around 3 per cent during the forecast period, supported by the low level of interest rates. Business conditions had improved further and faster growth in non-mining business investment was expected. Inflation was still expected to increase gradually as the economy strengthened. However, a further appreciation of the exchange rate would be expected to result in a slower pick-up in inflation and economic activity than currently forecast.

Employment growth had been stronger over recent months, so the forecasts for the labour market were starting from a stronger position. Forward-looking indicators suggested that the degree of spare capacity in the labour market would continue to decline gradually. Wage growth had remained low but was still expected to increase a little as conditions in the labour market improved. Members observed that recent strong employment growth would be likely to contribute to an increase in household disposable income, and therefore consumption growth, over the forecast period. However, ongoing low wage growth and the high level of debt on household balance sheets raised the possibility that consumption growth could be lower than forecast.

Members regarded conditions in the housing market and household balance sheets as continuing to warrant careful monitoring. Conditions in the housing market varied considerably around the country. While there were signs that conditions in the Sydney and Melbourne markets had eased somewhat, housing price growth in these two cities had remained relatively strong. In some other housing markets, prices had been declining. Borrowers investing in residential property had been facing higher interest rates and growth in credit to investors had eased, but overall housing credit growth had continued to outpace the relatively slow growth in household incomes.

Taking account of the available information and the need to balance the risks associated with high household debt in a low-inflation environment, the Board judged that holding the stance of monetary policy unchanged would be consistent with sustainable growth in the economy and achieving the inflation target over time.

The Decision

The Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1.5 per cent.