Suncorp Group Limited today reported NPAT of $1,075 million (FY16: $1,038 million) for the 12 months to 30 June 2017, an increase of 3.6%. They announced a a final dividend of 40 cents per share fully franked, bringing the total dividend to 73 cents per share (FY16: 68 cents) which represents a payout ratio of 81.9% of cash earnings. The results were helped by overall lower provisions. The repricing of mortgages helped also, but despite this bank NIM fell and home lending past due rose a little. So, its still a tough gig!

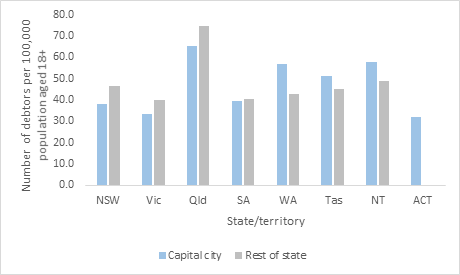

Suncorp is a complex portfolio of businesses, with a significant concentration in Queensland, so you have to look at each element. Given our focus on retail banking we will dive a little deeper there.

Suncorp is a complex portfolio of businesses, with a significant concentration in Queensland, so you have to look at each element. Given our focus on retail banking we will dive a little deeper there.

The Insurance business delivered NPAT of $723 million, up 30%, due to strong top-line growth and lower claims costs. The General Insurance business continued to see strong progress in remediating claims cost issues in the Home and Motor portfolios. GWP increased by 3.9% following strong growth in New South Wales CTP, premium increases in Home and Motor products and the successful entry into the South Australian CTP scheme. Commercial insurance GWP reduced 2.2% as pricing increases and strong retention in the SME segment was offset by lower retention in the Corporate segment. Reserve releases of $301 million (FY16: $348 million) remain well above long-term expectations of 1.5% of Group net earned premium (NEP). Life Insurance planned margins and underlying profits remained stable.

Suncorp’s additional reinsurance aggregate cover purchased for FY17 created significant shareholder value and increased resilience to natural hazards. Given the success in FY17, a similar cover has been purchased for FY18. The new cover provides $300 million of cover once the retained portion of natural hazard events greater than $10 million exceeds a total of $475 million. The retained natural hazards allowance has increased to reflect the higher natural hazards costs experienced in recent years.

The upper limit on Suncorp’s main catastrophe program, which covers the Group’s Home, Motor and Commercial Property portfolios for major events, will remain unchanged at $6.9 billion for the 2018 financial year.

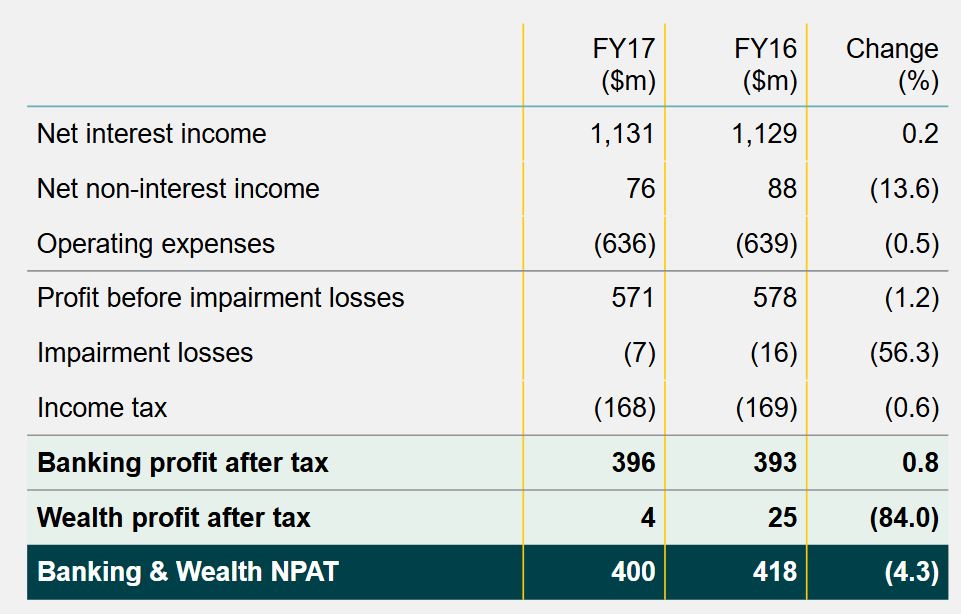

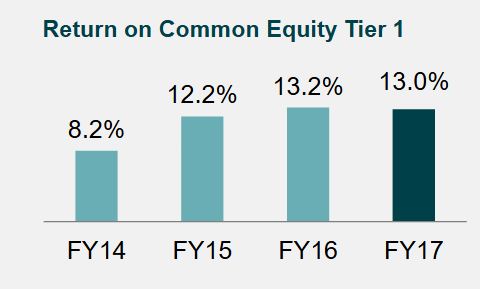

The Banking & Wealth business delivered NPAT of $400 million, impacted by investment in the Core Banking and Wealth platforms to support Suncorp’s strategy.

The Banking business achieved NPAT of $396 million with a focus on sustainable profitable growth while adapting to changing economic and regulatory dynamics.

The Banking business achieved NPAT of $396 million with a focus on sustainable profitable growth while adapting to changing economic and regulatory dynamics.

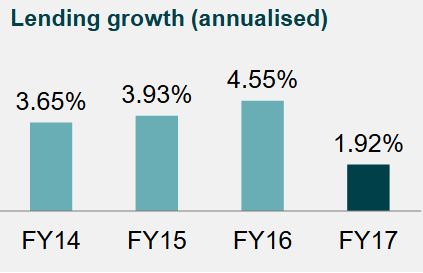

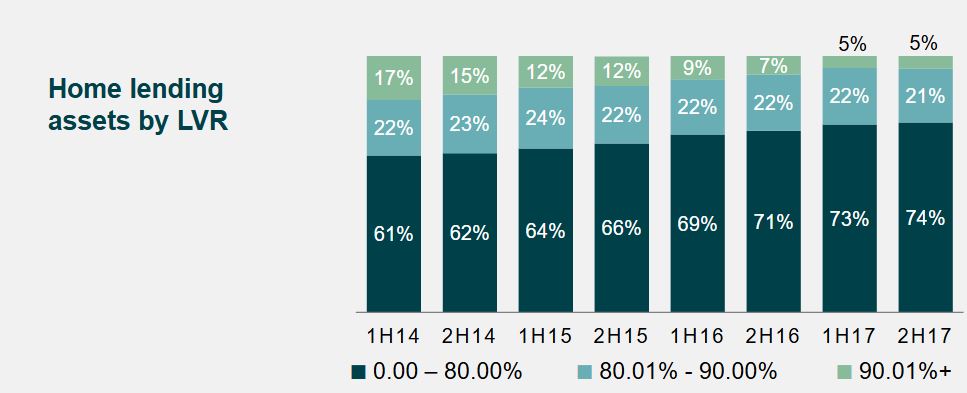

Lending growth of 1.9% reflected improved momentum in the second half of the financial year. They have throttled back on higher LVR loans.

Lending growth of 1.9% reflected improved momentum in the second half of the financial year. They have throttled back on higher LVR loans.

Home lending remains a large part of the business, with about three quarters of loans principal and interest, and with a concentration in Queensland.

Home lending remains a large part of the business, with about three quarters of loans principal and interest, and with a concentration in Queensland.

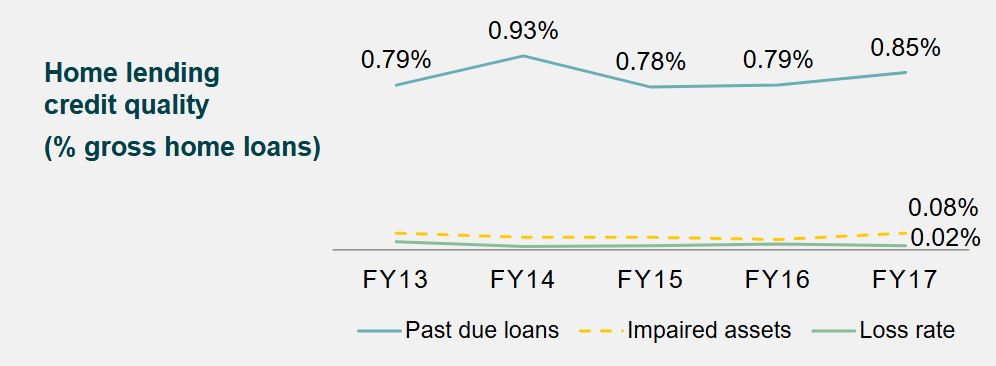

The past due has risen this past year.

The past due has risen this past year.

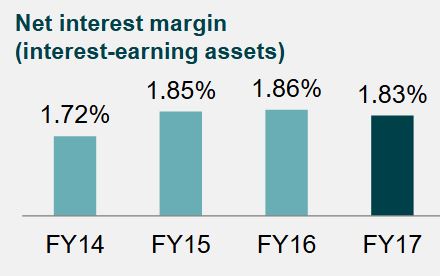

NIM of 1.83% reflects targeted repricing of mortgage rates, but is still down on FY16.

NIM of 1.83% reflects targeted repricing of mortgage rates, but is still down on FY16.

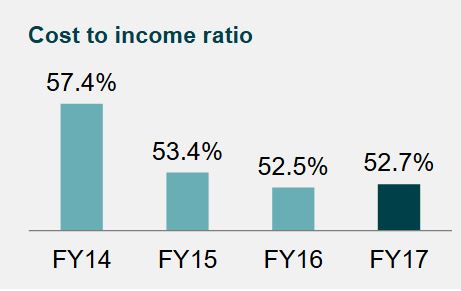

The cost to income ratio of 52.7% was a result of stable operating expenses and the subdued growth environment.

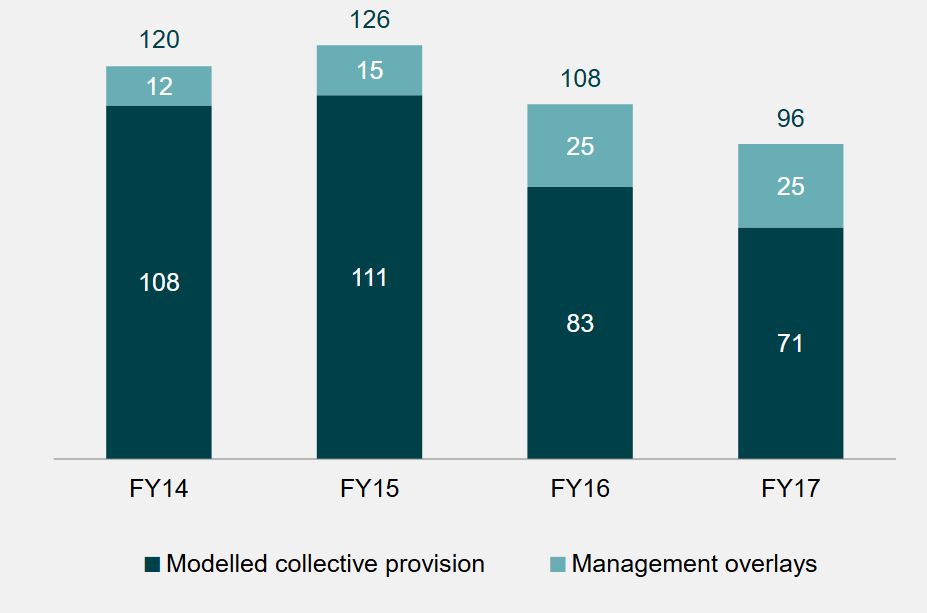

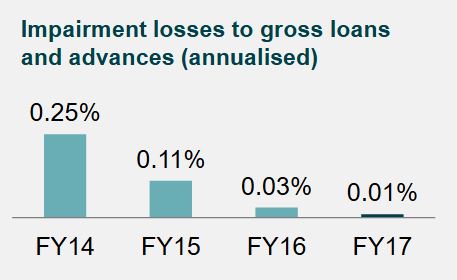

Impairment losses reduced to $7 million, representing 1 basis point of gross loans and advances.

Impairment losses reduced to $7 million, representing 1 basis point of gross loans and advances.

The Wealth business NPAT of $4 million reflects the cost of completing the Super Simplification Program and lower investment returns. Funds under management and administration increased by 0.8%.

They continue to drive “Project Ignite” (migration of core banking to its new Oracle platform), but said they would halt the migration of deposits and transaction banking products while it waits on upgrades from the vendor.

New Zealand achieved NPAT of A$82 million, impacted by claims costs associated with the Kaikoura earthquake and the associated reinsurance reinstatement expense. New Zealand General Insurance profit reduced to A$45 million, however underlying ITR was above the Group’s target of 12%. GWP growth of 6.3% was primarily driven by the Motor and Home portfolios. New Zealand Life Insurance delivered NPAT of A$37 million with a stable underlying profit of A$39 million, offset by negative market adjustments. During the financial year, the New Zealand business disposed of its Autosure motor insurance business. The sale resulted in a release of capital of A$30 million and will be accretive to the New Zealand long-term return on equity. A goodwill write-off of A$25 million has been included as a non-cash item in the Group result.

Capital and Dividend

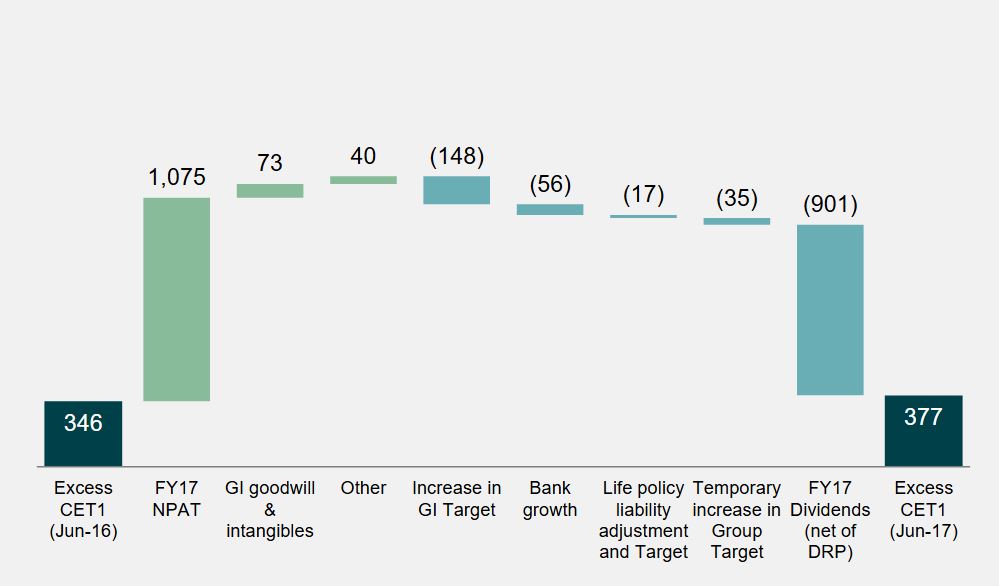

The Board has determined a fully franked final dividend of 40 cents per share. This brings total ordinary dividends for the 2017 financial year to 73 cents per share, up 7.4%. This represents a dividend payout ratio of 81.9% of cash earnings, slightly above the top end of the 60% to 80% dividend payout range and reflects the Board’s confidence in the outlook for the Group.

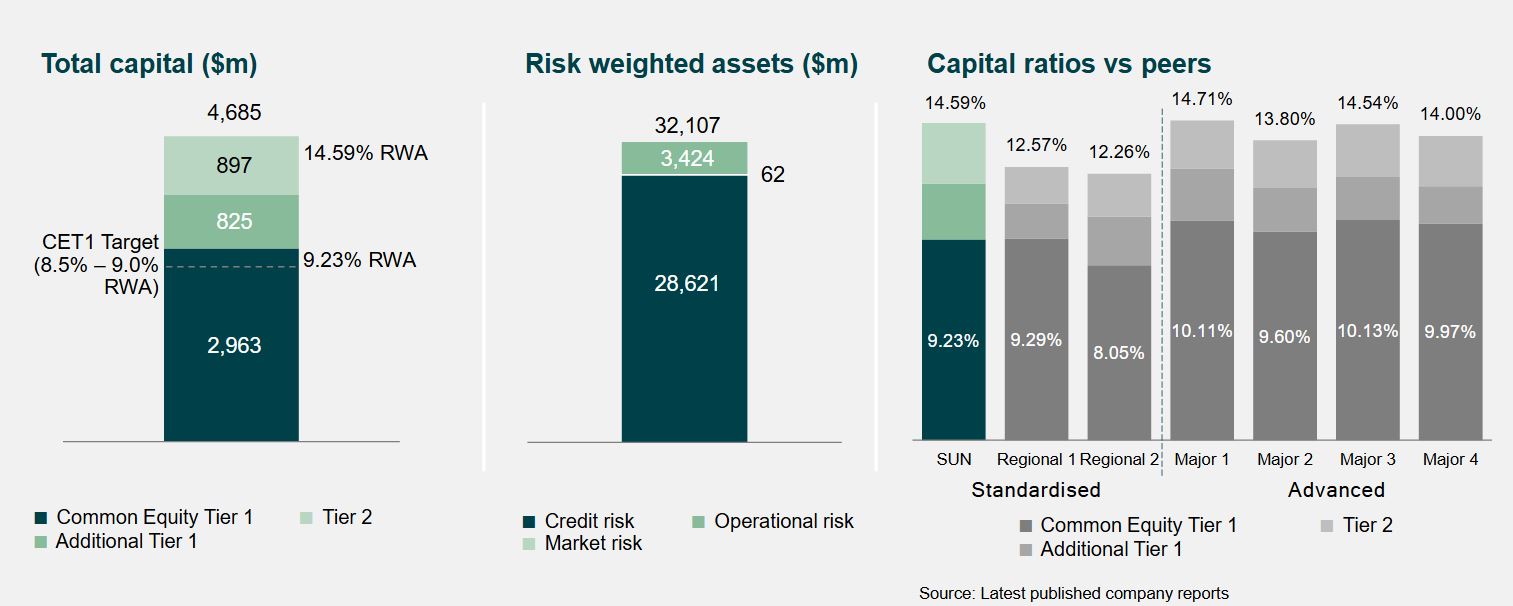

After accounting for the final dividend, the Suncorp Group’s Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) is $377 million above its operating targets.

After accounting for the final dividend, the Suncorp Group’s Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) is $377 million above its operating targets.

The General Insurance CET1 is 1.32 times the Prescribed Capital Amount and Bank CET1 is 9.23% are above the top end of their target ranges.

The General Insurance CET1 is 1.32 times the Prescribed Capital Amount and Bank CET1 is 9.23% are above the top end of their target ranges.

The Group has $235 million of franking credits available after the payment of the final dividend. It has a strong capital position.