Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen gave a good speech on Tuesday, promising to super-size Labor’s planned banking royal commission.

Originally intended to flush out illegal and deceptive activity in the banks, a royal commission should, he says, spring clean their legal activities too because that’s where the real damage to the economy is occurring.

Actually, Labor doesn’t need a royal commission to address the problem Mr Bowen described – namely, the hodge-podge of regulations being used to deal with the housing-credit bubble. A bit of well-written legislation would do the job just fine.

He is right, however, that we have a problem.

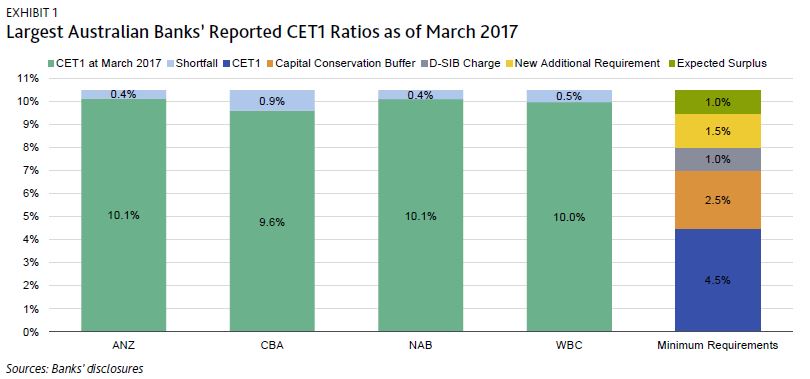

The key regulators who influence bank behaviour – the Reserve Bank, the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority and the Australian Securities and Investment Commission – are discharging their duties admirably, but are still somehow allowing the banks to gobble up more and more of Australian life.

Australia’s growing private debt to GDP ratio, he points out, is second only to Switzerland’s, at 123 per cent.

Mr Bowen spoke about the need for banks to be “unquestionably strong”, complained about the “composition of the property market, investors versus owner-occupiers”, and repeated regulators’ concerns that household debt is making the economy less resilient.

Well that’s all true. But if he wants to sharpen his rhetoric, he’d should reframe those comments from the perspective of young Australians.

Intergenerational wipe-out

In the space of just 70 years Australians climbed a home ownership mountain, only to find themselves sliding down the other side.

After World War II, only half of private sector homes were owned, either with or without a mortgage, by their occupants.

That climbed rapidly to peak at 71.4 per cent in 1966 – a level that fluctuated a bit, but was essentially maintained until the turn of the millennium.

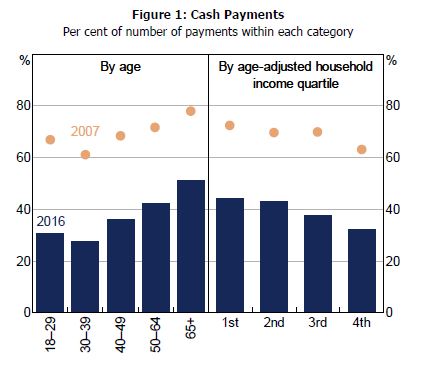

But as the housing-credit bubble inflated, and prices sky-rocketed, the home ownership rate started sliding – from 69.5 per cent in 2002, to 67 per cent at the 2011 census, and to 65.5 per cent last year.

This is a direct result of the debt bubble that Mr Bowen acknowledged in his speech, and which he rightly points out has been inflated by the property-investor tax breaks of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount.

But wait, it gets worse. It is the younger generations – new entrants to the housing market – where all the damage is being done.

Twenty- and thirty-somethings are either being locked out of the market forever or taking on budget-crushing mortgage repayments.

Some among those age groups may eventually receive large inheritances from their property-owning parents – assuming, that is, that today’s sky-high valuations do not tumble in the years ahead.

But for those that do not, one of two dismal economic futures awaits.

Firstly, the members of ‘Generation Rent’, on present settings, will face an under-funded retirement.

That’s because Australia’s superannuation system, and the complementary state pension, were calibrated in the early 1990s for a nation in which most people did not have to pay rent in retirement.

Secondly, the young Australians ‘lucky’ enough to secure huge mortgages will wave goodbye to a proportionally larger chunk of their household budget each month over the next 25 or 30 years, if they wish to actually pay off their homes.

Low interest rates, remember, only reduce the interest bill. The principal repayments not only stay the same in nominal terms, but in a low interest-rate environment they are ‘eroded’ more slowly by inflation.

Get to the root of the problem

So the problem, as Mr Bowen defines it, is the overlap and confusion of “ad hoc” attempts by regulators to head off disaster – particularly APRA’s attempts to slow mortgage lending.

But surely it’s better to remove the cause of those policy contortions than to unscramble the omelette.

As it happens, Labor last year pledged to reduce the wealth-redistributing and bubble-inflating tax incentives of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount.

That policy should go further, but at least it’s a good start.

So, yes, let’s have a royal commission into the illegal practices of the banks.

But as for ending the perfectly legal attack on the finances of young Australians, Labor only has to deliver what it’s already promised.