RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle spoke at the RBA Conference 2018 “Twenty-five Years of Inflation Targeting in Australia“.

There are a number of open issues worth considering. Most obvious is the question of the link between inflation targetting and financial stability. Would price level targetting offer a better alternative? Some argue this delivers predictability of the price level over a long horizon. Then there are questions about the correct level to target. More broadly, is it still relevant?

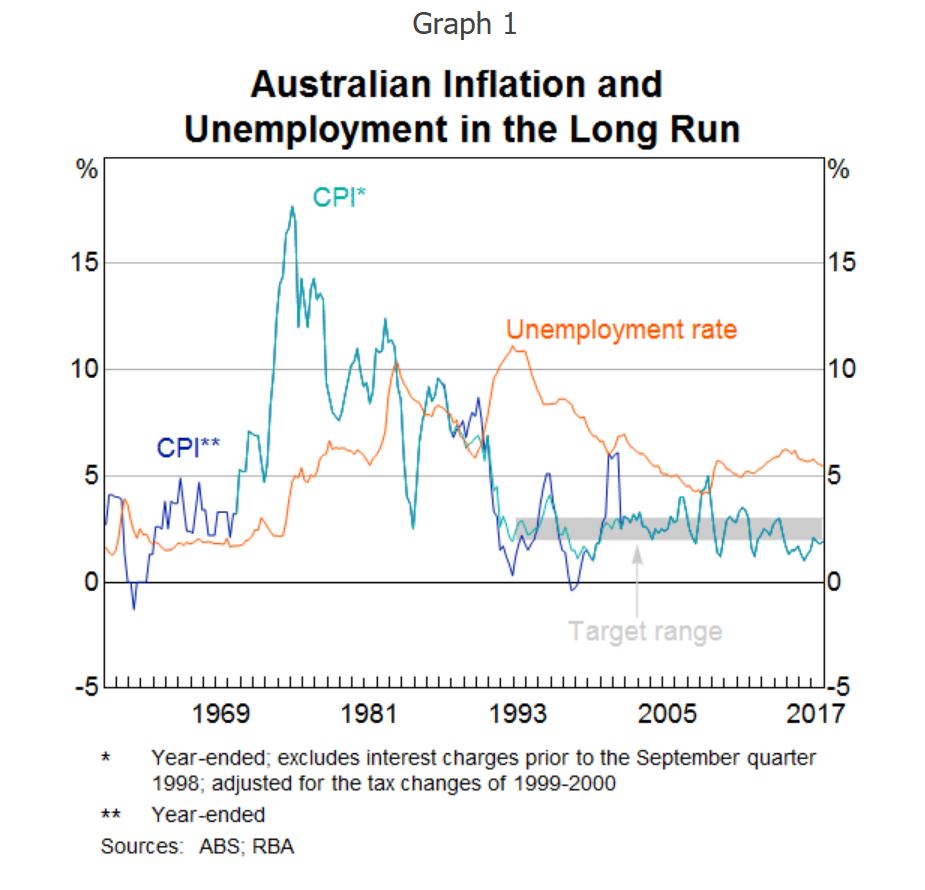

And in addition we would ask, as inflation targetting relies on the CPI dataset, are these telling the full story, or not?

It has been 25 years since Australia adopted an inflation-targeting regime as the framework for monetary policy. At the time of adoption, inflation targeting was in its infancy. New Zealand had announced its inflation target in 1989, followed by Canada and Sweden. The inflation-targeting framework was untested and there was little in the way of academic analysis to provide guidance about the general design and operational principles. Practice was very much ahead of theory.

Now 25 years later, inflation targeting is widely used as the framework for monetary policy. While there are differences in some of the features across countries, the similarities are more pervasive than the differences. And generally, the features of inflation-targeting frameworks have tended to converge over time.

It is interesting to firstly examine how the inflation-targeting framework in Australia has evolved over the 25 years. Secondly, it is also timely to reassess the appropriateness of the regime.

Open Issues

I have argued that the inflation target has delivered macroeconomic outcomes that have been beneficial for the Australian economy. I think a strong case can be made that it has contributed materially to better economic outcomes than the monetary frameworks that preceded it. I have also noted that the framework in Australia has not changed much over the 25 years of its operation, with the notable exception of communication.

So does that mean that the current configuration of the inflation target is the most appropriate or that even that is the most appropriate framework for monetary policy? What changes could be contemplated? Those questions are going to be addressed in other papers at this conference. But let me raise some here and discuss issues worth considering around each of them.

The first is the role of financial stability in an inflation-targeting framework. The Reserve Bank research conference last year considered this issue at some length. As I said earlier, financial stability is now articulated in the Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy. I talked about this issue at the Bank of England last year and Ben Broadbent is addressing it at this conference. One question that arises is how the financial stability goal interacts with the inflation target. Is it a separate goal that sets up potential trade-offs or is it aligned with the inflation-targeting goal? In the latter case, a potential reconciliation is the time horizon. When it materialises, financial instability is likely to be detrimental to inflation and unemployment/output: the global recession of 2008 and the subsequent slow recovery in a number of economies bears testament to the potential costs of financial instability (although here in Australia we didn’t experience this to as great an extent). So over some time horizon, potentially quite long, the inflation target and financial stability are aligned. But translating this into monetary policy implications over a shorter time horizon is a large challenge, which still seems to me to be far from resolved.

What about alternative regimes? Price level targeting is one that has been considered in some countries, including Canada, and has been proposed in the academic literature. One argument for a price level target is that it delivers predictability of the price level over a long horizon. It is not clear to me that this is something that is much valued by society. By revealed preference, the absence of long-term indexed contracts suggests that the benefits are not perceived to be high. I struggle to think of what contracts require such a degree of certainty. To me the benefits mostly derive from having inflation at a sufficiently low level that it doesn’t affect decisions. That supports an inflation target rather than a price level target. One important difference is that an inflation target allows bygones to be bygones, whereas a price level target does not. In a world where there are costs to disinflation (and particularly deflation), the likely small gains from the full predictability of the price level that comes with a price level target are not likely to offset the costs of occasional disinflations following positive price level shocks. Another challenge is how fast the price level should be returned to its target level. This presents both a communication and operational challenge as the speed is likely to vary with the size of the deviation.

While the argument at the moment is that a price level target allows the central bank to let the economy grow more strongly after a period of unexpectedly low inflation, again I do not think that practically this will deliver better outcomes than a flexible inflation target. That is an empirical question in the end which is worth testing.

The appropriate level of the inflation target is currently being debated in some parts of the world, including the US. The argument for a higher target rate of inflation is that it might reduce the risk of hitting the zero lower bound because a higher inflation rate would result in a higher nominal interest rate structure. In thinking about this, we should ask the question as to whether what we have seen is the realisation of a tail event in the historical distribution of interest rates (for a given level of the real interest rate).? While this event has now lasted quite a long time, if you thought it was a tail event, then you would expect the nominal rate structure to revert back to its historical mean at some point. If it is a tail event, and the world has just been unlucky enough to have experienced a realisation of that tail event, then there would not obviously be a need to raise the inflation target. We also need to question whether the real interest rate structure has shifted lower permanently, because of permanently lower trend growth say, which would also shift down the nominal rate structure and increase the likelihood of hitting the zero lower bound.

Also, as with price level targeting, in thinking about this question, it needs to be taken into account that it is highly beneficial to have the inflation target at a level where it doesn’t materially enter into economic decision-making. Two to three per cent seems to achieve that. We know that some number higher than a 2–3 per cent rate of inflation will materially enter decision-making, because we have had plenty of experience of higher rates of inflation that demonstrates that. How much higher though, we don’t really exactly know.

Another consideration in answering the question of whether the inflation target is at the right level is the range of policy instruments in the tool kit. Over the past decade, this tool kit has expanded in a number of central banks. For example, we now know that the zero lower bound is not at zero. Asset purchases have been utilised and these have included sovereign paper but also assets issued by the private sector. An assessment of the effectiveness of these instruments is still a work in progress. We also need to think about whether they are part of the standard monetary policy tool kit or whether they should only be broken out in case of emergency.

Nominal income targeting is another alternative regime to inflation targeting. I am not convinced that flexible inflation targeting of the sort practiced in Australia is significantly different from nominal income targeting in most states of the world. I also think that there are some quite significant communication challenges with nominal income targeting. Firstly, nominal income is probably more difficult to explain to people than inflation. Secondly, as a very practical matter, nominal income is subject to quite substantial revisions, which poses difficulties both operationally and again in communicating with the public.

Finally, one criticism of inflation targeting more generally is that central banks are fighting the last war. The fact that for a number of years now, inflation globally has been stubbornly low is not obviously the signal to declare victory over inflation and move on. Indeed, the declaration of victory may well be the signal that hostilities are about to resume and that inflation will shift up again. Moreover, even if victory can be declared that doesn’t mean you should go off to fight another war in another place without securing the peace. Inflation targeting can help secure the peace.

“And in addition we would ask, as inflation targeting relies on the CPI dataset, are these telling the full story, or not?”

Consider one group of Australians excluded by the RBA’s use of the ABS CPI dataset: first home buyers.

Assume you’re a first home buyer living in city X in Australia on a wage of $50,000 which is going up on average of 2% per year and the average house price in city X is $500,000 increasing at 7% per year.

You’re gross wage is going up by $1,000 per year and the average house is going up by $35,000 per year.

How is it OK that the RBA excludes the increase in house prices from the perspective of a first home buyer working full-time?

Does the RBA have a mandate to ensure their definition of inflation has nothing to do with what the Australian public want to achieve?