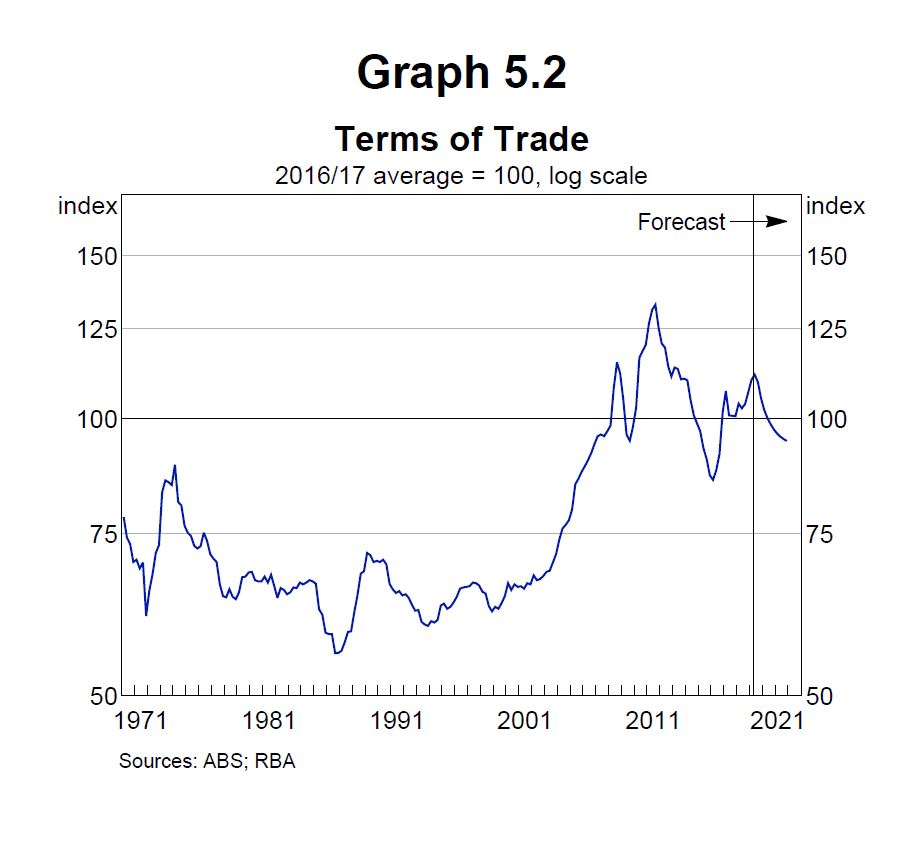

The latest Statement On Monetary Policy to me seem too optimistic, partly because of the accelerated risks internationally, and partly because their rose tinted spectacles appear to have been turned up to 11! Remember the current rate of growth is weakening, and the trade balance is flattered by ultra-high iron ore prices, which are now coming back. And frankly the statement appears to be an attempt to post rationalise their past poor decisions. We do agree the Government needs to do more, even if the “surplus” is sacrificed as a result.

Lowe’s opening address this morning, where he outlines the main points.

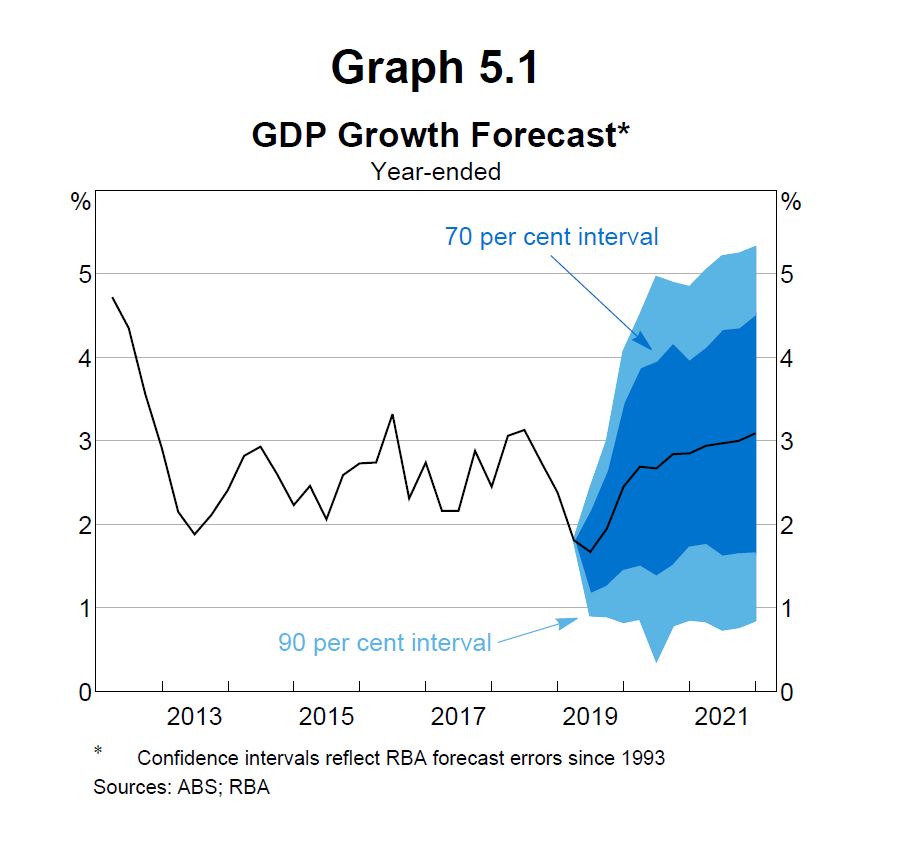

Our central forecast is for the Australian economy to expand by 2½ per cent this year and 2¾ per cent over 2020.

The growth forecast for this year has been revised down since we met six months ago, but the forecast for next year is unchanged. The downward revision this year mainly reflects weak consumption growth. It has become increasingly clear that the extended period of unusually slow growth in household incomes has been weighing on household spending, as has the adjustment in the housing market. Given this experience, the outlook for consumption continues to be the main domestic source of forecast uncertainty.

Even so, looking ahead, there are signs the economy may have reached a gentle turning point. Consistent with this, we are expecting the quarterly GDP growth outcomes to strengthen gradually after a run of disappointing numbers. This outlook is supported by a number of developments including: lower interest rates, the recent tax cuts, a depreciation of the Australian dollar, a brighter outlook for investment in the resources sector, some stabilisation of the housing market and ongoing high levels of investment in infrastructure. It is reasonable to expect that, together, these factors will see growth in the Australian economy return to around its trend rate next year.

The major uncertainty continues to be the trade and technology disputes between the United States and China. These disputes pose a significant risk to the global economy. Not only are they disrupting trade flows, but they are also generating considerable uncertainty for many businesses around the world. Worryingly, this uncertainty is leading to investment plans being postponed or reconsidered. It is also now generating volatility in financial markets and has increased the prospects of monetary easing in many countries. This means that we have a lot riding on these disputes being resolved.

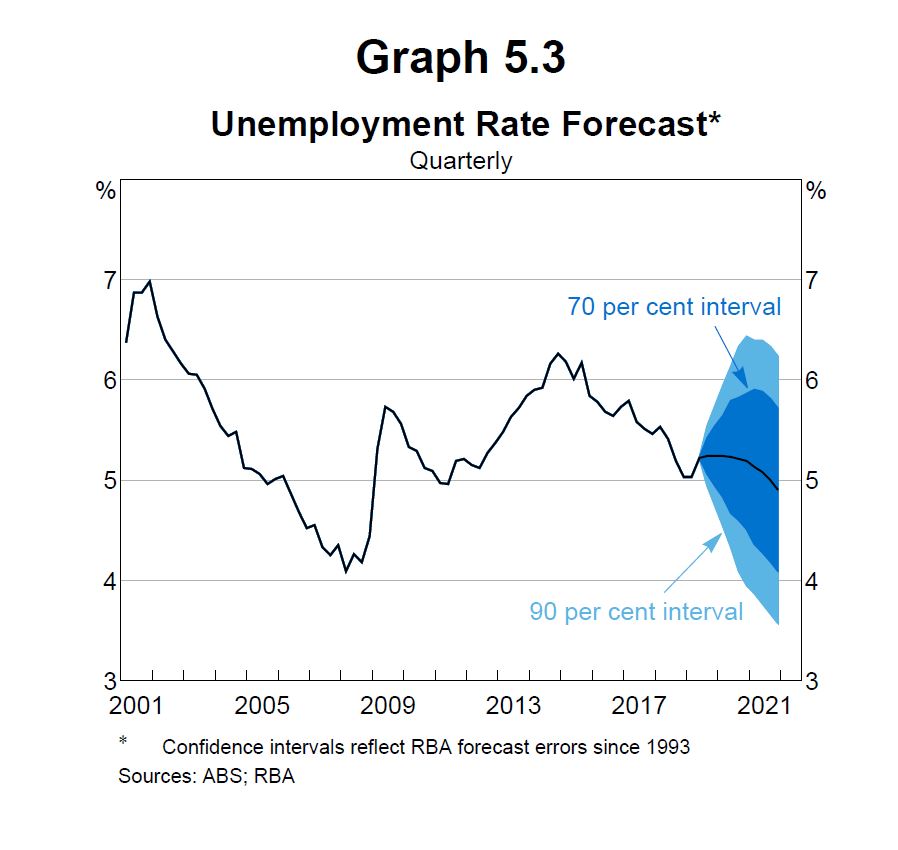

Turning now to the Australian labour market, the unemployment rate, at 5.2 per cent, is a little higher than when we met six months ago. This is despite employment growth having been stronger than we had expected. What has happened is that increased demand for labour has been met with more labour supply, especially by women and older Australians. Reflecting this, a higher share of the Australian adult population is participating in the labour market than ever before. This is good news. But one side-effect of this flexibility of labour supply is that it is harder to generate a tight labour market and so, in turn, it is harder to generate a material lift in aggregate wages growth.

Looking forward, while some slowing in employment growth is expected, the central scenario is for the unemployment rate to move lower to reach 5 per cent again in 2021.

If things evolve in line with this central scenario, it is probable that we will still have spare capacity in the labour market for a while yet, especially taking into account underemployment. This means that the upward pressure on wages growth over the next couple of years is likely to be only quite modest, and less than we were earlier expecting. Caps on wages growth in public sectors right across the country are another factor contributing to the subdued wage outcomes. At the aggregate level, my view is that a further pick-up in wages growth is both affordable and desirable.

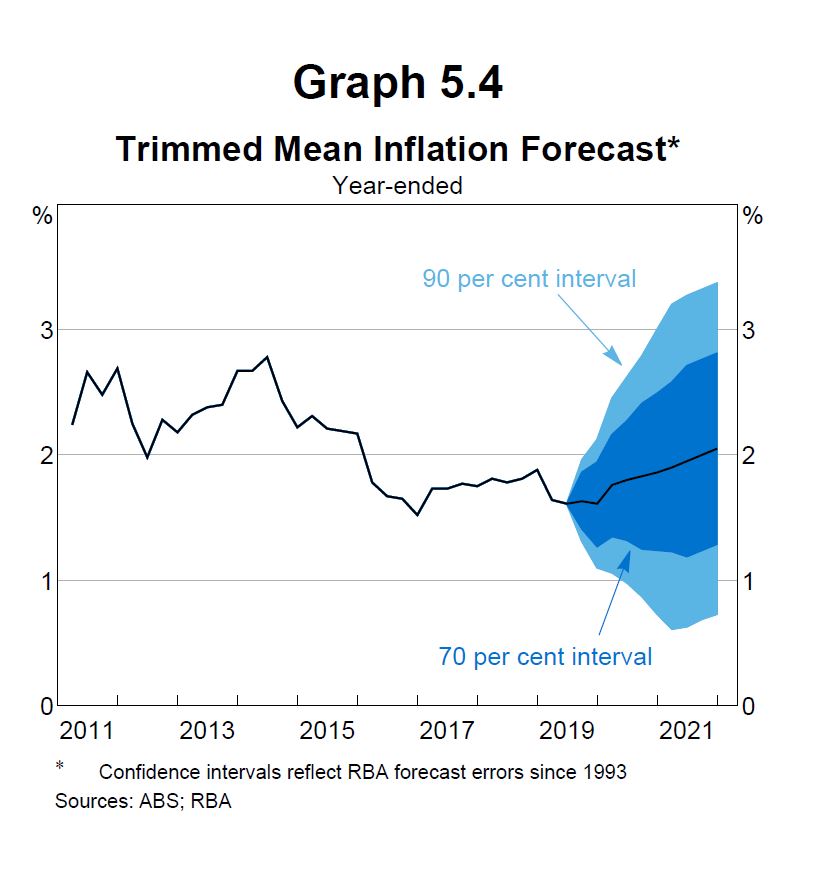

Turning now to inflation, the June quarter outcome was broadly in line with expectations, after a run of lower-than-expected numbers in earlier quarters. Over the year to June, inflation was 1.6 per cent, in both headline and underlying terms, extending the period over which inflation has been below the 2–3 per cent medium-term target range. The Reserve Bank Board remains committed to having inflation return to this range, but it is taking longer than earlier expected.

There are a few factors that I would highlight as contributing to the low inflation outcome over the past year. These are: the slow growth in wages; the ongoing spare capacity in the economy; various government initiatives to address cost-of-living pressures on households; and the adjustment in the housing market, which has contributed to unusually low increases in rents and declines in the price of building a new home in some cities. Working in the other direction, the drought and the depreciation of the exchange rate have been pushing some prices up.

Looking ahead, inflation is still expected to pick up, but the date at which it is expected to be back at 2 per cent has been pushed out again. Over 2020, inflation is forecast to be a little under 2 per cent and over 2021 it is expected to be a little above 2 per cent.

At this point, I would like to turn to monetary policy.

When we met with the Committee in February, I indicated that I thought the probabilities of a cash rate increase and a cash rate decrease were broadly balanced. Following that hearing, the situation continued to evolve and the Board reduced the cash rate twice – at its June and July meetings – to a new low of 1 per cent.

A reasonable question to ask is: what changed?

The answer is the accumulation of evidence that the economy could be on a better path than the one we looked to be on. The incoming data on wages, prices, GDP and unemployment all suggested that the Australian economy was some distance from running up against capacity constraints. It also suggested that the day at which inflation was comfortably back within the 2–3 per cent medium-term target range was not getting any closer.

Faced with this evidence, the Board decided that it was appropriate to lower the cash rate, after having kept it unchanged for more than 2½ years. It judged that a lower cash rate would boost jobs and help make more assured progress towards the inflation target.

In the current environment, easier monetary policy mainly works through two channels. The first is that it affects the exchange rate, which is now at the lowest level it has been for some time. The second is that it boosts aggregate household disposable income. I acknowledge that lower interest rates hurt the finances of the many Australians who rely on interest payments and the Board has paid close attention to this issue. At the aggregate level though, for every dollar the household sector receives in interest income, it pays well over two dollars in interest to the banks and other lenders. This means that lower interest rates put more money into the hands of the household sector and, at some point, this extra money gets spent and this helps the overall economy.

At its meeting earlier this week, the Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1 per cent.

It judged that after having moved twice in quick succession it was appropriate to wait and assess developments both internationally and domestically.

As I mentioned earlier, there have been a number of developments that could be expected to support the Australian economy over the next couple of years. Determining with precision the combined effect of these developments is difficult. It is certainly possible that their combined effect will be greater than the sum of the individual parts. If so, growth would surprise on the upside. Of course, it is also possible that the concerning international developments and the ongoing weak growth in household incomes could see the economy underperform our central scenario. The labour market will continue to provide an important guide as to which path we are on.

It is, nevertheless, reasonable to expect an extended period of low interest rates in Australia. This reflects what is happening both overseas and here at home.

While we might wish it were otherwise, it is difficult to escape the fact that if global interest rates are low, they are going to be low here in Australia too. When the global appetite to save is elevated relative to the appetite to invest – as it is now – interest rates in all countries are affected. Our floating exchange rate gives us the ability to set our own interest rates from a cyclical perspective, but it does not insulate us from long-lasting shifts in global interest rates driven by saving/investment decisions around the world.

In the central scenario that I have sketched today, inflation will be below the target band for some time to come and the unemployment rate will remain above the level we estimate to be consistent with full employment. While this remains the case, the possibility of lower interest rates will remain on the table. The Board is prepared to ease monetary policy further if there is additional accumulation of evidence that this is needed to achieve our goals of full employment and inflation consistent with the target. Time will tell.

As I have discussed on other occasions, if further stimulus to demand growth is required to get us to full employment and closer to the economy’s capacity, monetary policy is not the country’s only option. Monetary policy certainly can help, and it is helping, but there are certain downsides from relying too much on monetary policy.

One option is for fiscal support, including through spending on infrastructure. Spending on infrastructure not only adds to demand in the economy but, done properly, it can boost the economy’s productivity. It can also directly improve the quality of people’s lives through reducing congestion and improving services. At the moment, there are some capacity constraints in parts of the infrastructure sector, but these should not prevent us from looking for further opportunities to boost the economy’s productive capacity and support domestic demand. There is no shortage of finance to do this, with interest rates the lowest they have ever been. This week, all governments in Australia can borrow for 10 years at less than 2 per cent.

Another option is structural policies that support firms expanding, investing, innovating and employing people. A strong, dynamic business sector is the best way of creating jobs and growing the overall economy. We will all do better if Australia is viewed as a great place to expand, invest, innovate and employ people. A program of structural reform would help move us in this direction. It would also help boost productivity growth, which over recent times has slowed noticeably. If this slowing is maintained, it will become a serious issue and as a society we will have to make some difficult adjustments. So it is important that we think about the possibilities here, not just from a short-term perspective but from a long-term perspective as well.