An article published today in the NZ Reserve Bank Bulletin explores the potential effects of digital disruption to banks and broader financial system stability. Consumers now expect the same seamless digital services from banks as they receive from other industries. Hence, the banking industry is being ‘digitally disrupted’ as banks and technology firms race to meet this expectation.

This article explores whether the digital disruption of banking is a ‘disruption’ or more of a ‘distraction’ and aims to understand the concept of digital disruption of banking, what is driving it, what are the impacts on banks, and what are the impacts on financial system stability. It finds that the disruption is occurring in all areas of banking but particularly in retail customer interactions.

This article explores whether the digital disruption of banking is a ‘disruption’ or more of a ‘distraction’ and aims to understand the concept of digital disruption of banking, what is driving it, what are the impacts on banks, and what are the impacts on financial system stability. It finds that the disruption is occurring in all areas of banking but particularly in retail customer interactions.

Banks using new technologies to improve their services is not a new phenomenon. Over the late 1980s to 1990s automated teller machines (ATMs), electronic debit and credit cards, and telephone banking started replacing paper-based payments. Then, through 2000 to 2010, basic banking products became digitally available through the introduction of remote access to bank accounts via mobile banking and internet banking. However, these earlier digital trends were predominantly driven by the supply side (i.e. by banks themselves) to improve the cost efficiency of supplying banking services, and therefore improve profitability.

This current wave of digitisation is different to earlier periods of innovation in the banking industry in that it is primarily driven by consumers rather than banks. Consumers now expect more accessible, convenient and smarter transactions (using internet and mobile devices) when accessing and managing their finances, as they have experienced this convenience in other activities such as shopping and transportation. Advances in new technologies and the changing customer expectations have enabled non-bank firms, such as large technology companies (for example Amazon, Facebook and Google) and start-ups (for example PushPay, Moven and Harmoney), to provide innovative bank-like services and take a share of the banking industry profits. These firms can be referred to as ‘disruptors’.

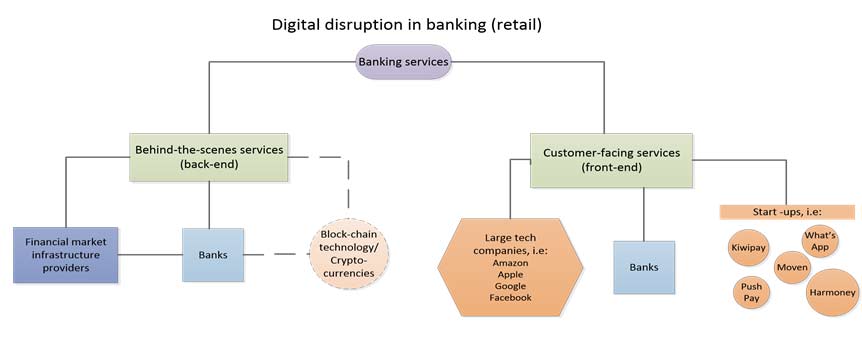

The emergence of disruptors poses a threat to the traditional banking model and is referred to as the disruption of the banking industry. A survey by Efma and Infosys Finacle (2015) revealed that 45 percent of banks viewed global technology companies as high threat and 41 percent of banks also viewed start-up companies as high threat. Under the current model of retail banking most services are provided by banks. However, after the digital disruption of banking, ‘front-end’ (or ‘customerfacing’) banking services such as the sales and distribution of banking products, account management and payment instructions may also be provided by disruptors. However, disruptors do not appear to be engaging in ‘back-end’ services such as holding deposits and settling payments because these activities tend to be captured by prudential regulation which makes them more expensive to provide due to additional compliance costs.

‘Millennials’ (the generation born 1981–2000) appear to be driving this ‘disruption’ of banking services. A three-year survey of views of 10,000 Millennials in the United States reported that the banking industry was the industry with the highest risk of disruption due to the Millennials’ low loyalty towards banks and expectations that technology companies could service their banking needs better. The survey found that:

-

71 percent of respondents would rather go to the dentist than hear from their bank,

-

one in three respondents was open to switching banks,

-

nearly half of the survey participants were counting on the change to traditional banking models to come from technology start-ups; and

-

73 percent of respondents indicated they would be more excited about a new financial product offering from Google, Amazon, Apple, PayPal or Square than from their bank.

Banks’ core roles are to act as an intermediary between depositors and borrowers, help manage risks for depositors and lenders, and provide payment services. In fulfilling these roles the banks provide security and convenience to the depositors and access to credit for borrowers. Banks are also key agents in the creation of money (via fractional reserve banking), distribution of notes and coins, and are part of the transmission of monetary policy (via the rates charged for loans and paid on deposits). A central question is if and how this ‘digital disruption’ described in the previous section will affect the bank’s core roles or whether this disruption is limited to the banks’ retail distribution models and interactions with consumers. It appears that digital disruption will impact both the retail distribution and customer interaction models of banks, as well as potentially disrupting the core role of banks.

A survey by McKinsey&Company of the customer segments and products of 350 globally leading financial technology firms (or leading ‘disruptors’) revealed that all banking segments are at risk of disruption. However, the main area of concentration of these disruptors is the retail sector, and the various products and services tied to payments, lending and financing.

A key potential effect of digital disruption on banks in the short to medium term is the loss of profitable activities and services.

In the long term, banks’ role in the financial system may be challenged. Disruptors may become systemically important if they supply a large portion of front-end banking services. For example, if peer-to-peer or equity lending platforms grow rapidly then it is possible that a significant number of credit decisions could be made by lending platforms. Likewise it is possible a significant number of payments may be initiated using mobile wallets.

If banks lose profits generated at the front-end of banking services they may become less resilient in an economic downturn. Stress test results reveal that the profitability of New Zealand banks provides a buffer against losses in downturn scenarios where a large number of creditors default on their loans. Lower profitability results in a smaller buffer against potential losses caused by an economic downturn, and also reduces access to international capital markets as the cost of funds increases in proportion to the riskiness of the bank.

In a more hypothetical long term scenario, banks may be challenged to change the fundamental model of banking in order to meet the demands of Millennials as they progress through life. As described above, digital disruptors are more likely to have a stronger relationship with younger customers (or Millennials) which could pose a considerable threat to the business models of incumbent banks.

In the short to medium term, digital disruption may result in new risks and increased instability in the financial system. For example, peer-to-peer lenders do not take on credit risk in the same manner as a bank, they do undertake decisions on behalf of lenders and so may introduce different operational risks to the borrowing and lending process. Likewise, payments innovations may introduce new operational risks to the payments system.

Further, as banks undertake core banking system redevelopment projects this may increase project risks to the banking system. Large technology projects commonly run over time and over budget and if these projects are not managed appropriately they could result in significant disruptions to customer services and bank profitability.

In the medium to long term, digital disruption of the banking sector may improve the efficiency of the financial system. For example, new payments providers increase the speed and ease of initiating payments for consumers, and the application of new technologies (such as ‘blockchain’) could increase the speed and reduce the cost of making cross-border payments. In addition, P2P platforms reduce the cost of matching borrowers with lenders as there are no physical branches to maintain.

The long term impact of digital disruption on financial system soundness is less clear. Soundness may be reduced if existing banks’ profitability buffers are reduced due to increased competition from digital disruptors. However, digital disruption may also improve financial system soundness if it results in more competitors entering the banking sector and fewer systemically important banking entities. This may reduce the impact of a single entity failure. Further, this may alleviate the ‘too-big-to-fail’ risk where authorities may feel pressured to prevent large banks from failing due to systemic concerns. This would in turn, reduce the probability of banking entities taking on risks that they are not willing to bear (moral hazard).

The introduction of new ‘digital’ competitors is driving banks to respond with digital strategies including the modernisation of their core banking systems. Digital disruption may impact financial stability both positively and negatively, and the Reserve Bank continues to monitor it closely.