A really excellent speech by Claudio Borio, Head of the Monetary and Economic Department of the BIS, at the Cato Institute in which he questions three deeply held beliefs that underpin current monetary policy received wisdom and cites Mark Twain “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The speech draws two conclusions. First, the well known trend decline in real interest rates is, at least in part, a disequilibrium phenomenon, not consistent with lasting financial, macroeconomic and monetary stability and unusually easy monetary policy spreads globally.

Second there is a need to adjust current monetary policy frameworks so that monetary policy plays a more active role in preventing systemic financial instability and its huge macroeconomic costs. This calls for taking financial booms and busts more systematically into account. Financial booms sap productivity by misallocating resources.

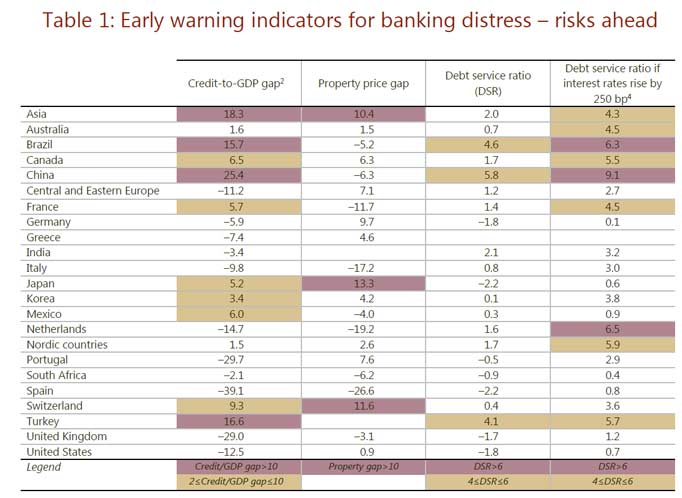

One slide in particular caught my attention. It is Table 1: Early warning indicators for banking distress – risks ahead.

The three beliefs he questions are worth thinking about:

The three beliefs he questions are worth thinking about:

- Is it appropriate to define equilibrium (or natural) rates as those consistent with output at potential and with stable prices (inflation)?

- Is it appropriate to think of money (monetary policy) as neutral, ie as having no impact on real outcomes, over medium- to long-term horizons relevant for policy – 10-20 years or so, if not longer?

- Is it is appropriate to set policy on the presumption that deflations are always very costly?

He finds that there are good reasons to question these three deeply held beliefs underpinning monetary policy received wisdom.

First, defining equilibrium (or natural) rates purely in terms of the equality of actual and potential output and price stability in any given period is too narrow an approach. An equilibrium rate should also be consistent with sustainable financial and macroeconomic stability – two sides of the same coin. Here, he highlighted the role of financial booms and busts, or financial cycles.

Second, money (monetary policy) is not neutral over medium- to long-term horizons relevant for policy – 10–20 years or so, if not longer. This is precisely because it contributes to financial booms and busts, which give rise to long-lasting, if not permanent, economic costs. Here he highlighted the neglected impact of resource misallocations on productivity growth.

Finally, deflations are not always costly in terms of output. The evidence indicates that the link comes largely from the Great Depression and, even then, it disappears if one controls for asset price declines. Here he highlighted the costs of asset price, especially property price, declines and the distinction between supply-driven and demand-driven deflations.

Therefore, the long-term decline in real interest rates since at least the 1990s may well be, in part, a disequilibrium phenomenon, not consistent with lasting financial, macroeconomic and monetary stability. Here he highlighted the asymmetrical monetary policy response to financial booms and busts, which induces an easing bias over time.

There is a need to adjust monetary policy frameworks to take financial booms and busts systematically into account. This, in turn, would avoid that easing bias and the risk of a debt trap. Here he highlighted that it is imprudent to rely exclusively on macroprudential measures to constrain the buildup of financial imbalances. Macroprudential policy must be part of the answer, but it cannot be the whole answer.