According to Moody’s, on 7 January, UK trade unions published their annual report, which warned about a credit crisis as UK average non-mortgage household debt jumped above £15,000, almost 50% higher than before the 2008 financial crisis. The increase in household debt leaves borrowers vulnerable to sudden economic stress, such as that which might crystallise in a no-deal Brexit scenario. An incremental increase in unemployment would have negative consequences for highly leveraged consumers. Higher joblessness, reduced real wages and, to a lesser extent, lower refinancing availability would increase delinquencies and defaults in consumer loan pools backing residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) and asset-backed securities (ABS).

Additionally, softening house prices can exacerbate the negative effect of rising defaults on RMBS. In case of a severe economic stress, the macroeconomic outlook for the UK would weaken, leading to a decline in house prices nationwide, which would have a mixed effect regionally across the UK. We expect more negative consequence in regions with higher unemployment and in industries that are more materially affected by such a stress scenario. However, we expect that any deceleration in house prices will be less severe than during the 2008-09 financial crisis given less inflationary stresses within the market. The performance of buy-to-let (BTL) and nonconforming transactions would weaken, especially for some recently originated collateral pools that have assets with relatively weaker underwriting standards. The performance of credit card ABS collateral would also deteriorate, especially for those pools with more exposure to highly leveraged obligors.

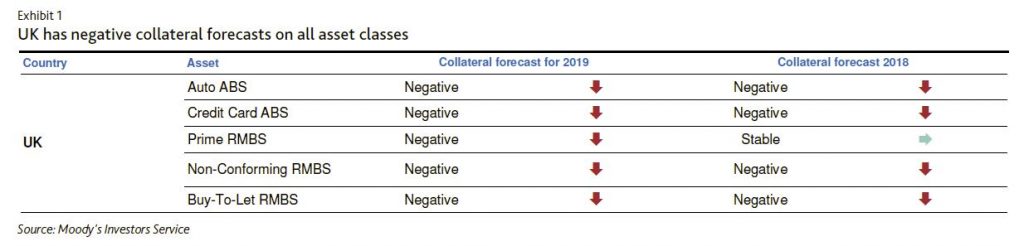

We have negative collateral forecasts for all UK consumer sectors

Our forecasts are negative for all UK consumer sector collateral. Our collateral performance forecasts over the next 12-18 months address the direction of expected losses for the market in general, not specific collateral pools among the deals we rate.

In normal circumstances, the absolute level of household debt is not necessarily as important as affordability measures such as the ratio of payment or loan to disposable income. Given the low interest rate environment, affordability is still relatively high for UK borrowers. However, sudden economic stress that leads to negative real wage growth and increasing unemployment has the potential to change matters.

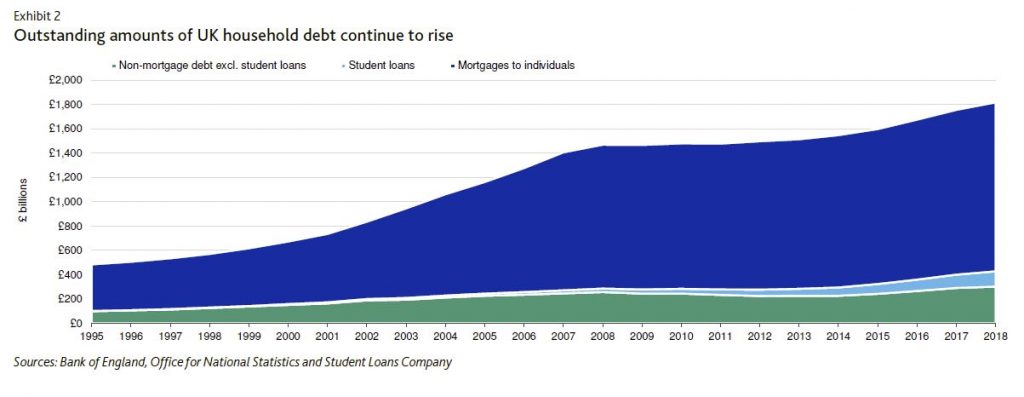

The average household debt figure in the trade union’s analysis is based on data from Bank of England, Office for National Statistics and the Student Loans Company. It excludes mortgages but includes everything else (i.e., credit cards, personal loans, payday loans and student loans), which deviates from the Bank of England’s definition of non-mortgage household debt.

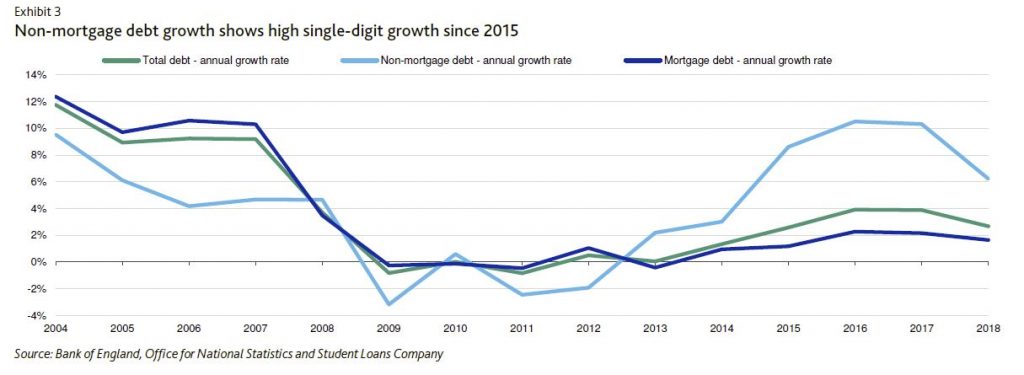

The rapid growth of non-mortgage (mainly unsecured) debt has contributed to household debt since 2013 after years of constrained credit in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The growth patterns of mortgage and non-mortgage debt have switched gears compared with pre-crisis patterns: non-mortgage debt (e.g., credit cards and consumer loans) have had a high single-digit growth rate since 2015, with slightly slowing growth in 2018 to a level of 6%, whereas pre-crisis, mortgage debt had these high growth rates. The 2018 data shows that UK households had average non-mortgage debt of approximately £10,000, even excluding student loans, and this is in line with levels reported in 2008.