Interesting research is contained in a BIS Working Paper “Interest rates and house prices in the United States and around the world“.

They show that home prices are indeed connected to interest rates, and changes in rates do have a flow on effect to prices, and that there are spillover effects, especially relating to interest rates in the USA.

This means that as the FED lifts rates, as is now well signalled, we should expect prices to fall here and in other countries. There may be some delay, the modelling is complex, and the relationships are not straight forward. But it is is worth remembering that in the US real house prices fell by as much as 31% over the course of 2007–09!

This paper estimates the response of house prices in 47 advanced and emerging market economies (EMEs) to changes in short- and long-term interest rates. Our study has four novel aspects. First, we analyse in some detail the impact of short-term interest rates on house prices. Second, we look at the responsiveness of house prices around the world to US interest rates. Third, we use a unique data set on house prices compiled by the BIS in cooperation with national statistical and monetary authorities. And fourth, our empirical framework tries to capture the important role of inertia in house prices.

One striking feature of house price growth is its persistence. With the exception of Germany, Portugal and Switzerland, advanced economies have seen real house prices growing by an average of at least 6% per year for 40 years or longer. In the United States, for instance, this resulted in a 13-fold increase in real house prices over a period of 47 years; in Norway, in a 77-fold increase over 66 years. And in South Africa, real house prices increased nearly 150 times over half a century.

Another way to appreciate the persistence of house prices is to contrast the length of their upswings and downswings. We define an upswing (downswing) as a period of house price increases (decreases) sustained in an individual country for three years or more. Based on this definition, periods of upswing accounted for nearly 80% of the advanced economy sample. The upswings lasted on average 13 years; with the longest one, in Australia, still continuing after half a century. By contrast, downswings accounted for only 8% of the advanced economy sample; they lasted on average five years, and the longest one, in Japan, lasted 13 years. In EMEs, upswings accounted for two thirds of the sample. They lasted on average eight years, and the downswings four years.

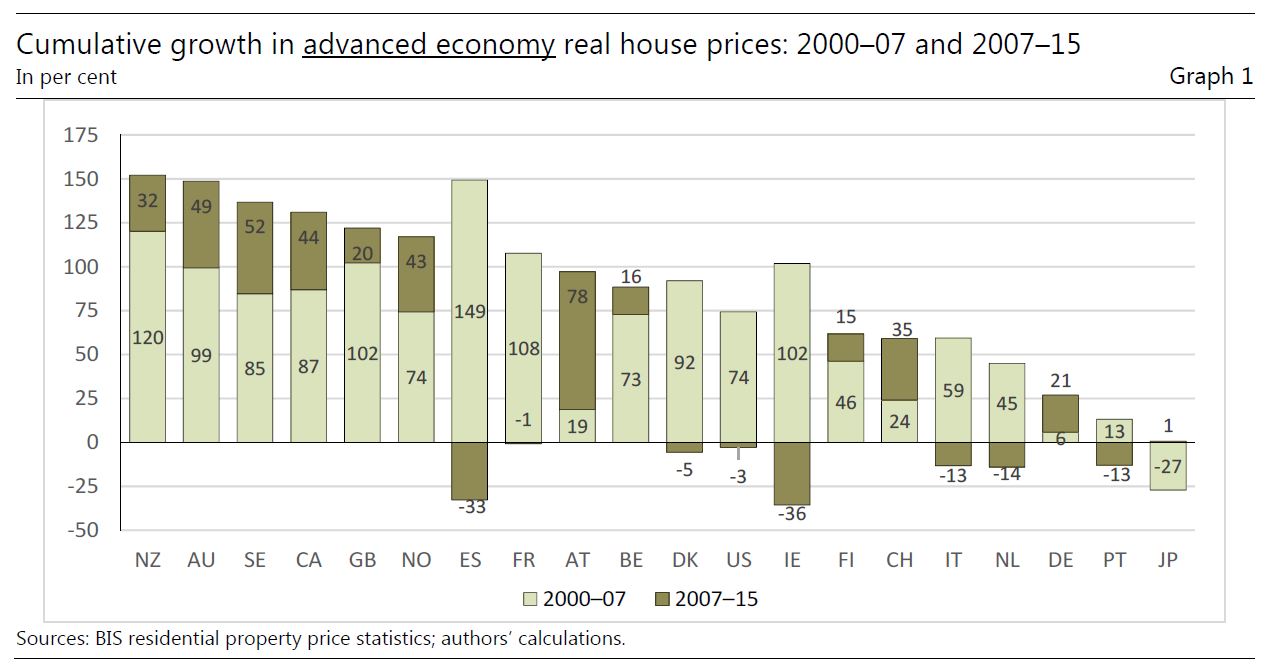

The surge in house prices has been particularly pronounced since the turn of the millennium. Between 2000 and 2015, real house prices increased by 100% or more in half the economies in our sample. Most countries experienced a housing boom before 2007 (light bar segments). But many have also seen very rapid house price growth since 2007 (dark bar segments). These included Australia, Austria, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland among advanced economies; and Brazil, Hong Kong SAR, Israel, Malaysia and Peru among EMEs.

Our focus on short-term interest rates is motivated by their link to monetary policy. As a house is a long-lived asset, the interest rate appropriate for relating the service flow from a house to its price is arguably a long-term rate. However, house prices also depend importantly on ease of access to credit, which is in turn significantly affected by the monetary policy stance. Bernanke and Blinder (1992), for instance, showed that changes in the US federal funds rate were associated with changes in lending by US banks, an effect that has become known as the bank lending channel of monetary policy. Short-term interest rates, which are more closely related to the stance of monetary policy, might therefore be just as important a “fundamental” for house prices as longer-term rates. Indeed, we find a surprisingly important role for short-term interest rates as drivers of house prices, especially outside the United States. Our interpretation is that this reflects an important role for the bank lending channel of monetary policy, especially in countries where securitisation of home mortgages is less prevalent.

The motivation for looking at the responsiveness of house prices around the world to not only domestic but also US interest rates is that the latter have become a key measure of the global cost of financing. We do find spillover effects from US interest rates, both short and long ones, on house prices outside the United States.

Our study draws on the BIS residential property price statistics and, in particular, the “preferred” house price series as identified by national statistical offices or central banks. We compiled over 1,000 annual observations on house prices for the non-US countries in our sample from these series and about a half century of quarterly house prices for the United States. We use these data to estimate the dynamic impact of changes in interest rates and other explanatory variables on real house prices around the world.

Most empirical studies assume that short-term interest rates do not influence house price growth other than through the domestic cost of borrowing, ie by their influence on long-term interest rates. The findings in this paper suggest that this view might be mistaken: changes in short-term interest rates seem to have a strong and persistent impact on house price growth.

Moreover, global, ie US short-term interest rates – not just domestic ones – seem to matter, both in advanced economies and EMEs. We interpret the relative importance of short-term interest rates in driving house prices as indicating an important role for the bank lending channel of monetary policy in determining housing financing conditions, especially outside the United States, where securitisation of home mortgages is less prevalent.

The larger effect of interest rates on house prices we find reflects in part the use in our regressions of a long distributed lag of interest rate changes. For the United States, our estimates for the period from 1970 to the end of 1999 suggest that a 100 basis-point fall in the nominal short-term rate, accompanied by an equivalent fall in the real short-term rate, generated a 5 percentage point rise in real house prices, relative to baseline, after three years. We find an even larger effect if we include the data through end-2015. For other advanced economies and EMEs, we estimate that a 100 basis-point fall in domestic short-term interest rates, combined with an equivalent fall in the US real rate, generates an increase in house prices of up to 3½ percentage points, relative to baseline, after three years. Another reason we find larger interest rate effects is by allowing for inertia in house price movements. We find strong evidence against the random walk hypothesis: real house prices around the world tend to move in the same direction for about a year after being hit by a disturbance, then exhibit a modest reversal.

We think that this inertia in house prices reflects the large search and transaction costs associated with trading residential real estate and shifting between owner-occupied and rental housing. These costs are ignored in the user cost model, which predicts a fairly high interest rate sensitivity for house prices.

Our findings also suggest a potentially important role for monetary policy in countering financial instability. While higher short-term interest rates alone cannot significantly dampen the demand for housing, slower house price growth can give supervisors more time to implement measures to strengthen the financial system. At the same time, the finding that house prices adjust to interest rate changes gradually over time suggests that modest cuts in policy rates are not likely to rapidly fuel house

price bubbles.

Note: BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The papers are on subjects of topical interest and are technical in character. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS.