The US 10-year bond rate is moving higher again, with the expectation of more FED rate rises ahead.

US mortgage rates have resumed an upward trend that began last week after political turmoil in Italy began to die down. More simply put, rates had been rising in mid May.

US mortgage rates have resumed an upward trend that began last week after political turmoil in Italy began to die down. More simply put, rates had been rising in mid May.

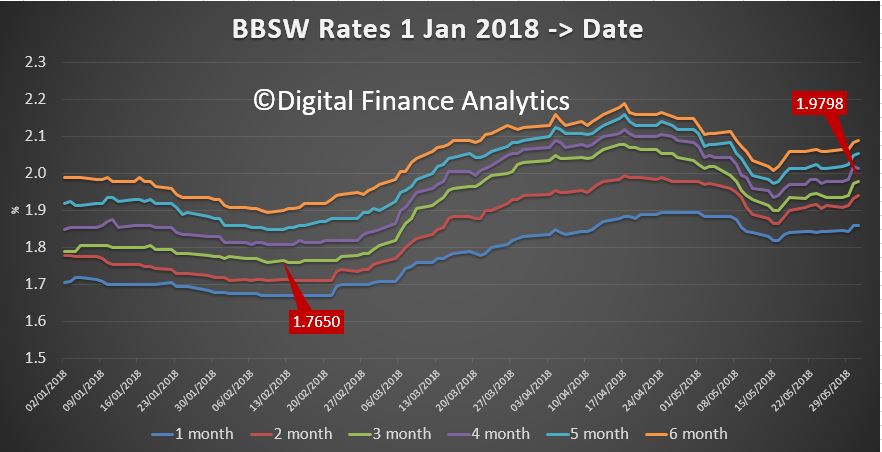

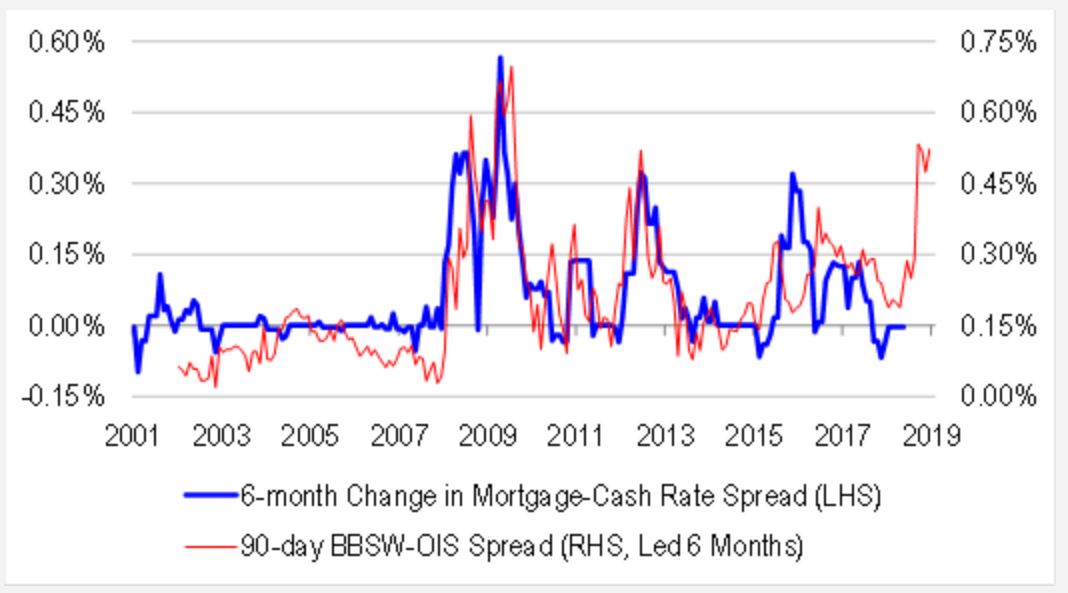

Locally, I continue to track the BBSW (the critical benchmark)..

Locally, I continue to track the BBSW (the critical benchmark)..

… and rates are still elevated, if off their highs. This is an indication of the influence of overseas funding, and the question of trust in the local markets following the Royal Commission revelations, recent court cases and now the latest suggestions of cartel behaviour.

… and rates are still elevated, if off their highs. This is an indication of the influence of overseas funding, and the question of trust in the local markets following the Royal Commission revelations, recent court cases and now the latest suggestions of cartel behaviour.

But the question is, to what extent are these movements in short term rates hitting Australian bank margins, and will they react by repricing their back books?

There is first the “optics”, given the current focus on their poor behaviour as laid bare in the recent rounds of hearings. Banks who hike rates risk more reputational damage (can it go lower?), although some, such as Suncorp and MyState have already reacted by lifting rates. And if you look carefully average mortgage rates are already a little higher, and deposit rates continue to be cut. But all done quietly, and not enough to repair margins.

Second, the current behaviour we are seeing is the offer of significant discounts for some new and refinanced mortgage loans, especially principal and interest loans with lower LVRs, because banks need to grow their mortgage books to sustain shareholder returns. And mortgage growth is slowing.

Third, its worth understanding what proportion of bank funding is based on short term, and overseas funding. Perfectly timed was a speech – Some Features of the Australian Fixed Income Market, by Christopher Kent, RBA Assistant Governor (Financial Markets) in Tokyo.

The reduced use of offshore funding by the banks has been offset by much greater use of domestic deposits . The big shift away from short-term debt towards deposits started around the time of the global financial crisis. These changes were in response to the demands of the market and those of regulators for banks to make greater use of more stable sources of funding.

While the use of short-term debt (i.e. less than one year) is less than it was, it still accounts for around 20 per cent of banks’ funding. And about 60 per cent of that debt (on a residual maturity basis) is raised offshore. Global money markets, in the United States and elsewhere, provide the Australian banks with a much deeper market with a wider investor base than the relatively small domestic market. This short-term debt is issued in foreign currency terms, but the banks fully hedge their exchange rate (and interest rate) exposures at relatively low cost.

Because Australian banks raise a portion of their funding in US money markets to finance their domestic assets, they responded to higher US rates earlier this year by marginally shifting towards domestic markets to meet their needs. Hence, the rise in the US 3-month LIBOR rate (relative to the Overnight Index Swap (OIS) rate) was closely matched by a rise in the equivalent 3-month bank bill swap rate (BBSW) spread to OIS in Australia; similarly, the two spreads have declined of late by similar orders of magnitude (relative to their respective OIS rates). Equivalent spreads in some other money markets around the world also moved higher, though to a lesser extent than spreads in Australia. In contrast, rates in the euro area and Japan were not affected by the tightness in the US markets. That difference appears to reflect the fact that although European and Japanese banks tap into US money markets, they do so largely to fund US dollar assets.

Changes in BBSW rates in Australia feed through to banks’ funding costs in a number of ways. First, they flow through to rates that banks pay on their short- and long-term floating rate wholesale debt. Second, BBSW rates affect the costs associated with hedging the risks on banks’ fixed-rate debt, with the banks typically paying BBSW rates on their hedged liabilities. Third, interest rates on wholesale deposits tend to be closely linked to BBSW rates.

In short, the costs of a range of different types of funding have risen a bit for Australian banks in the past few months. But they remain relatively low and pressures in short-term money markets have eased, with BBSW about 10 basis points lower than its recent peak (relative to OIS). While some business lending rates are closely linked to BBSW rates – and so have increased a little – there have been few signs to date of changes to rates on loans for housing or small businesses.

Yeh, right…

In summary, banks are exposed to short term funding cost moves, 20% of the funding is short term, and 60% of that off-shore. As for the pressure on rates, well Credit Suisse just put out an interesting note highlighting the state of money markets.

Interbank credit spreads are back at financial crisis highs. And our modelling suggests that we should expect to see both sharp tightening of bank lending standards, and out of cycle rate hikes. Therefore, even without doing anything, the RBA will find that financial conditions are getting tighter.

A quick bit of modelling suggests that banks will need to lift rates, and soon to address the profit compression suggested in the money market movements (yet alone paying the various agreed settlement costs and fees in some banks’ operations). We discussed this a week or so back.

More mortgage stress to come then.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-prospa-ipo/australias-prospa-delays-listing-on-debut-day-after-regulator-queries-loan-terms-idUSKCN1J207C

I saw the CBA piously proclaiming they are changing how they deal with us (disreputable) brokers.

As a responsible broker and in compliance with “responsible lending guidelines” explain to me how I can refer any client to the CBA given it publicly recorded history of:

Stealing funds from borrowers loan accounts.

Selling insurance products that cannot be claimed on.

Enabling money laundering and terrorism financing.

Stealing money from children bank accounts.

The question I have is how does this company retain its banking licence after so many breaches of the law?

I think this is now a National Security issue / sovereign reputation issue and unless it is drastically, or more accurately the law is enforced as it should be, explain to me why any oversea’s entity would deal with a criminal organisation like the CBA?

Why would any overseas bank lend to the RBA in light of recent events, at the very least we will see increases in borrowing costs to reflect the risk of dealing with criminals who go unpunished.