The synchronised global economic growth that began in 2018 appears to be running its course, according to NAB.

‘Synchronised global growth’ was a favoured expression by economists and research houses at the end of last year, with each of the 45 major economies tracking upward growth.“All the major engines of growth in the global economy are now synchronised in an upward trajectory for the first time since the end of the global financial crisis,” EY global IPO leader Martin Steinbach noted in late December.

But according to the latest economic summary note by NAB senior economist Gerard Burg, this global growth rate may have reached its peak.

“Global growth was marginally softer in Q1, driven by a modest slowdown in the advanced economies,” Mr Burg wrote.

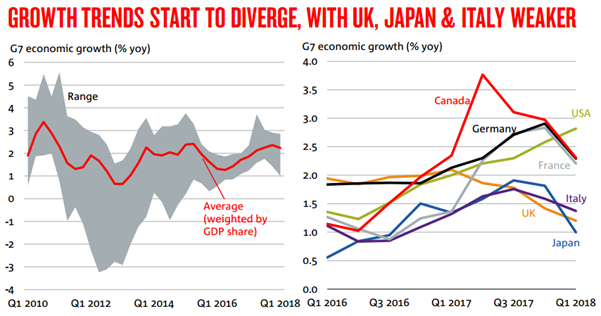

Growth in the major economies was 2.2 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2018, a small drop from the 2.4 per cent growth in the last quarter of 2017.

“Although this slowdown was modest, it points to a divergence in conditions across countries, which over recent years have displayed relatively synchronised growth.”

Where growth in Italy, the UK and Japan had fallen in Q1, growth in the US had in contrast accelerated to nearly 3 per cent year-on-year, Mr Burg said.

“Early indicators of growth point to strong conditions in the second quarter, highlighting some upside potential to advanced economy growth in the short term.

“That said, as the impact of the fiscal stimulus from the large package of tax cuts at the start of this year fade, we expect growth to slow back towards potential as capacity constraints start to bite and monetary policy tightens,” he noted.

While economic growth in major emerging markets edged incrementally higher in Q1 to “almost 6 per cent year-on-year (from 5.75 per cent in Q4 2017)”, “mixed” underlying trends were at play.

While India continued to rebound with 7.75 per cent growth, China and Indonesia’s growth remained “relatively stable”, and Brazilian and Russian economic growth both dropped.

“While emerging market export volumes have remained comparatively strong (relative to the post-GFC period), growth appears to have slowed in March,” Mr Burg said.

“The risks associated with retaliatory trade actions in response to US trade policy fall more heavily on emerging markets (given the higher export share of GDP).”

Indeed, escalating trade tensions – particularly revolving around US’ tariffs – has led to an “uncertain” global trade environment.

“It appears that the current global upswing has peaked (or is near that point),” Mr Burg added.

“That said, despite signs, many short- and long-term interest rates have started to increase, or will do so over the forecast period”.

“Our forecasts still imply above trend growth in both 2018 and 2019 before easing back to the long-term average of 3.5 per cent in 2020.”