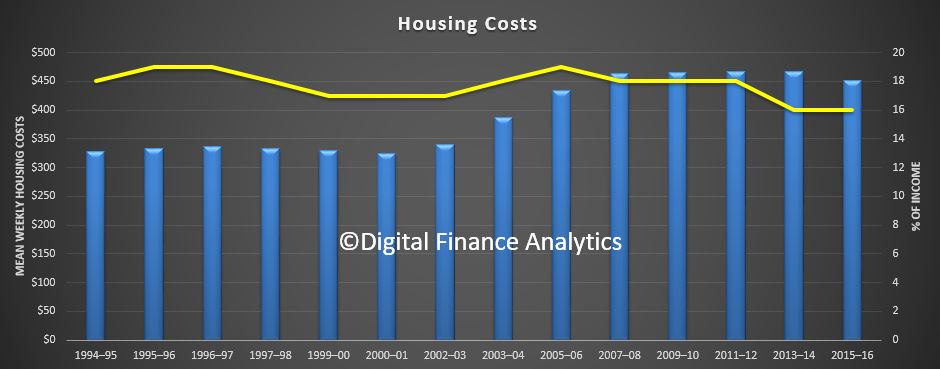

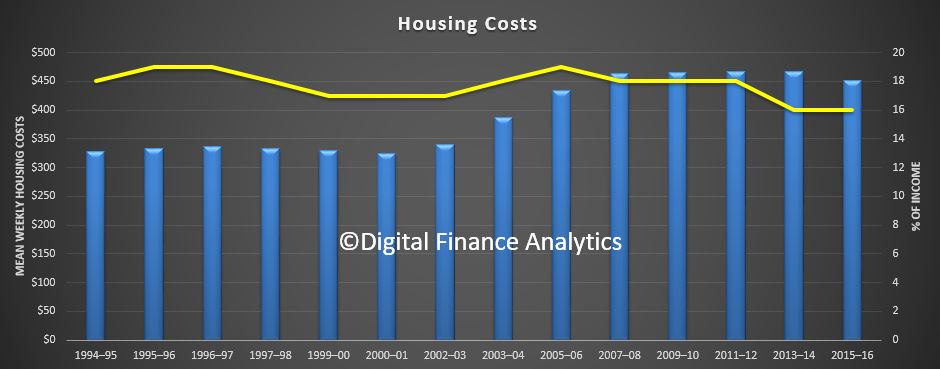

Data from the ABS today – Housing Occupancy and Costs – highlights the average household with an owner occupied mortgage is paying around $450 a week, slightly lower than the peak a couple of years ago. This equates to around 16% of gross household income, on average.

This does not include repayments on investment properties of course (and many households have multiple properties as investing in property rises).

But of course, the true story is interest rates have fallen to all time lows, allowing people to borrow more, as prices rise. As a result, should interest rates start to bite, this will cause real pain. Then of course we have recent flat wage growth, in real terms, in the past couple of years.

Also, households have a bigger mortgage for longer, which is great for the banks, but not helpful from a household perspective, as it erodes savings into retirement and more older Australians are still borrowing. And of course the current high home prices show a paper profit, but that could be eroded if prices slide.

Also, households have a bigger mortgage for longer, which is great for the banks, but not helpful from a household perspective, as it erodes savings into retirement and more older Australians are still borrowing. And of course the current high home prices show a paper profit, but that could be eroded if prices slide.

Thus, the ABS data should not be interpreted as everything is fine, it is not! In fact, underwriting standards should be much tighter now, as we highlighted this morning, Australian Banks are willing to go up to around 6 times income, higher than many other countries, with similar home price bubbles.

The proportion of income mortgagees are using for housing has declined over the last decade, according to new figures released today by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

“In 2005-06, owners with a mortgage paid 19 per cent of their total household income on housing costs. By 2015-16 this had fallen to 16 per cent. This is likely driven by lower interest rates coupled with growth in household incomes over the last decade, ” Dean Adams, Director of Household Characteristics and Social Reporting, said.

In 2005-06, owners with a mortgage paid $434 per week in housing costs, similar to the $452 paid in 2015-16 in real terms. But over the same period, average total household incomes for mortgagees rose from $2,272 to $2,759 per week.

“Mortgage and property values have also increased in the last decade. Ten years ago, the real median mortgage value was $171,000 which rose to $230,000 in 2015-16. Meanwhile, the real median dwelling value increased from $449,000 to $520,000,” Mr Adams explained.

Going back another decade, the results also reveal that households are entering into a mortgage at older ages. The proportion of younger households (with a reference person aged under 35 years) represented 69 per cent of first home buyers in 1995-96 which dropped to 63 per cent by 2015-16.

“Having a mortgage is now the most common form of ownership for households whose reference person was aged between 35 and 54 years. Among this group, ownership with a mortgage increased by 15 percentage points over the last two decades, from 41 per cent to 56 per cent. Meanwhile, the rate of outright ownership in 2015-16 (12 per cent) was one-third the 1995-96 rate (36 per cent),” Mr Adams said.

The rate of older households (with a reference person aged 55 years and over) who were still paying off a mortgage has tripled between 1995-96 and 2015-16 (from 7 per cent to 21 per cent). Older households are spending more of their income on housing costs than two decades ago, increasing from 8 per cent to 14 per cent for those aged between 55 and 64, and from 5 per cent to 9 per cent for those aged 65 and over.