And you might get a different answer depending on whether you’re talking about income inequality or wealth inequality. Income is the flow of economic resources over a certain time period, while wealth is the stock of resources built up over time.

We can draw some insights from the newly released Household Incomes and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) 2017 report, which reveals the latest results of a longitudinal study that has been running since 2001.

But it doesn’t show the whole story. Combining HILDA’s results with data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ income surveys gives a more comprehensive picture of trends in economic inequality in Australia.

HILDA data show lower income inequality than the ABS

Firstly, you need to know that when we are talking about income, most people are referring to the disposable income of the household, not individuals.

That’s all the income that members of a household receive from various sources, minus tax. You can then then adjust for the number of people in the household, accounting for the differing needs of adults and children to get what economists call “equivalised household disposable income”.

The HILDA survey, funded by the Department of Social Services and conducted by the Melbourne Institute, has followed some 17,000 individuals every year since 2001. (The most recent ABS income survey final sample consists of 14,162 households, comprising 27,339 persons aged 15 years old and over.)

One commonly used way to measure inequality is called the Gini coefficient, which varies between zero (where all households have exactly the same income) and one (where all the income is held by only one household). The Gini coefficient for equivalised household disposable income varies between about 0.244 in Iceland to 0.397 in the United States (with most other high income OECD countries falling between these two levels), but is as high as 0.46 in Mexico and 0.57 in South Africa.

The latest HILDA report puts Australia’s Gini coefficient at 0.296 and notes that it has “remained at approximately 0.3 over the entire 15 years of the HILDA Survey.”

The HILDA surveys show a lower level of income inequality than the ABS figures do. Some of the differences between these estimates will reflect the broader definition of income used by the ABS, and the significant changes in this definition over time.

In a sense, the HILDA longitudinal survey is like a video where the same people are interviewed every year, whereas the ABS surveys are like a snapshot of the Australian population taken every two years.

But there are also problems with longitudinal surveys because participants often drop out of the survey over time. Also the survey is based on people who were living in Australia in 2001, thus leaving out immigrants who have arrived since that time. While the survey has refreshed the sample in 2011 to address this problem, this attrition may reduce the representativeness of the sample. In addition, the sample size of the ABS surveys is about 50% greater than HILDA, which will reduce sampling errors.

ABS data show inequality has risen

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has conducted income surveys since the late 1960s, although it is only surveys since 1982 that are comprehensive and available for public analysis. These ABS surveys are also used in most of the international data sources that compare income inequality across countries – the OECD Income Distribution database and the Luxembourg Income Survey.

The ABS data show a clear increase in both wealth and income inequality over the mid- to long run.

The chart below shows two long series of estimates from the ABS surveys – those published in 2006 by researchers David Johnson and Roger Wilkins (who now oversees the HILDA survey) from 1981-82 to 1996-97, and official figures prepared by the ABS, from 1994-95 to 2013-14.

Despite the differences in income measures and equivalence scales, the long run trend from the ABS figures is clear.

There are periods in which inequality fell, but overall inequality rose over the whole period – including in the most recent period to 2013-14. The Gini coefficient in 2013-14 is a little lower than its peak just before the Global Financial Crisis, but the difference is not large.

True, there have been changes in the ABS’ survey methodology over the years but these changes should not have an effect after 2007-08, as income definitions haven’t changed in a major way since then.

Wealth is much more unequally distributed than income

The ABS also publish information on the distribution of net worth – that’s household assets minus liabilities. Wealth is much more unequally distributed than income.

According to the ABS, the Gini coefficient for net worth in 2013-14 was 0.605 (compared to a Gini coefficient for income of 0.333). This is a clear increase from a Gini of 0.573 in 2003-04.

Put another way, ABS data show a high income household in the richest 20% of the income distribution has an income around 5.4 times as high as the average household in the bottom 20% of the income distribution, as this chart demonstrates:

In contrast, ABS data show that on average households in the richest 20% of the distribution of net worth have wealth of around $2.5 million or more than 70 times higher than the net worth held on average by households in the bottom 20% of the wealth distribution, as this chart demonstrates:

Somewhat surprisingly, however, the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report puts wealth inequality in Australia at below the world average (and the mean and median levels of net worth at among the highest in the world).

This largely reflects the still high level of home ownership in Australia and the high levels of wealth in home ownership, which accounts for nearly half of total net worth on average.

Reconciling conflicting trends

While these two major sources of data show conflicting trends on income inequality, the ABS sample size is much greater. Ultimately, however, the reasons for the differences between the findings of the ABS and the HILDA survey are not obvious.

One way forward would be for the ABS and the Melbourne Institute to jointly analyse the differences between their findings to identify why their estimates of inequality diverge.

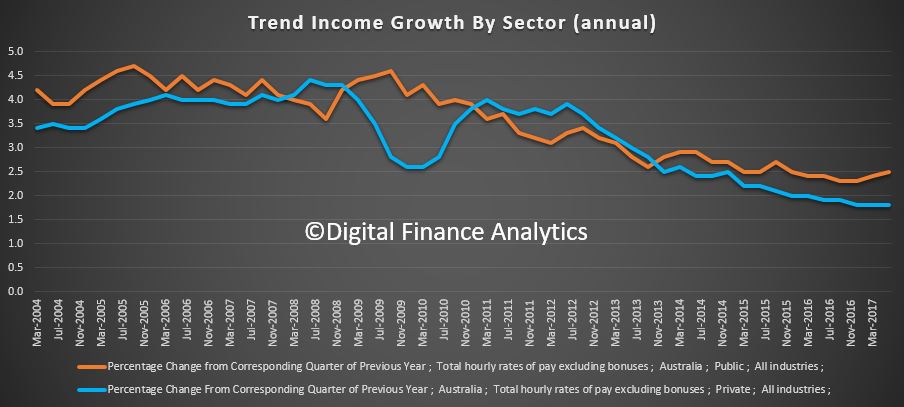

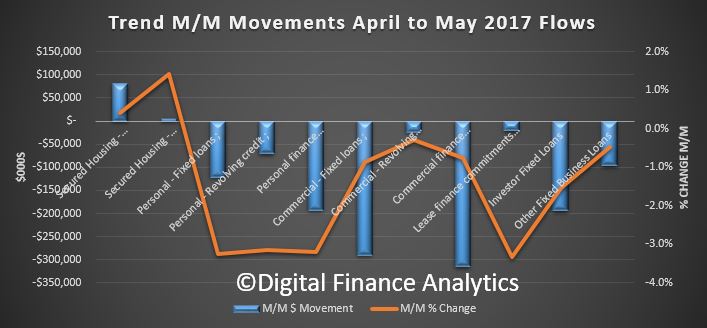

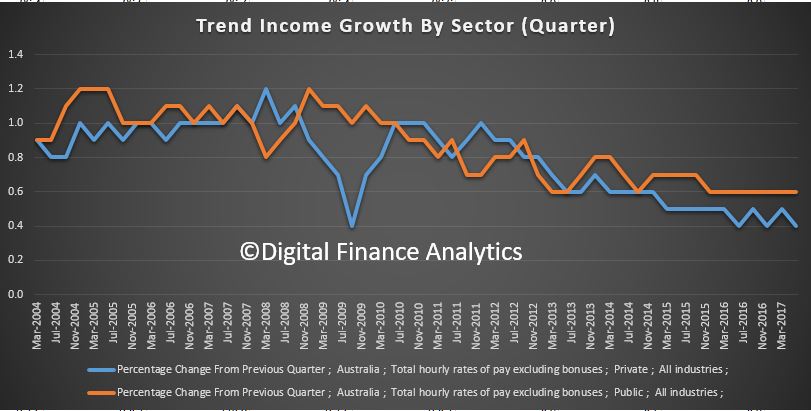

The annual trend is clear to see. Public servants are doing a little better than the private sector.

The annual trend is clear to see. Public servants are doing a little better than the private sector.