From The Conversation.

In a country as diverse as Australia, it is impossible to identify a set of characteristics that defines us. However, with today’s release of data from the 2016 Census, it is possible to identify some of the common characteristics, how they vary across states and territories, and how they are changing over time.

Australia undertakes a compulsory long-form census – where detailed information across several areas is required of every individual respondent – every five years.

Australia undertakes a compulsory long-form census – where detailed information across several areas is required of every individual respondent – every five years.

So, what did we learn from the first set of results? According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS):

The 2016 Census has revealed the ‘typical’ Australian is a 38-year-old female who was born in Australia, and is of English ancestry. She is married and lives in a couple family with two children and has completed Year 12. She lives in a house with three bedrooms and two motor vehicles.

Australia is getting a bit older; the typical Australian in 2011 was aged 37.

How do today’s results vary across Australia?

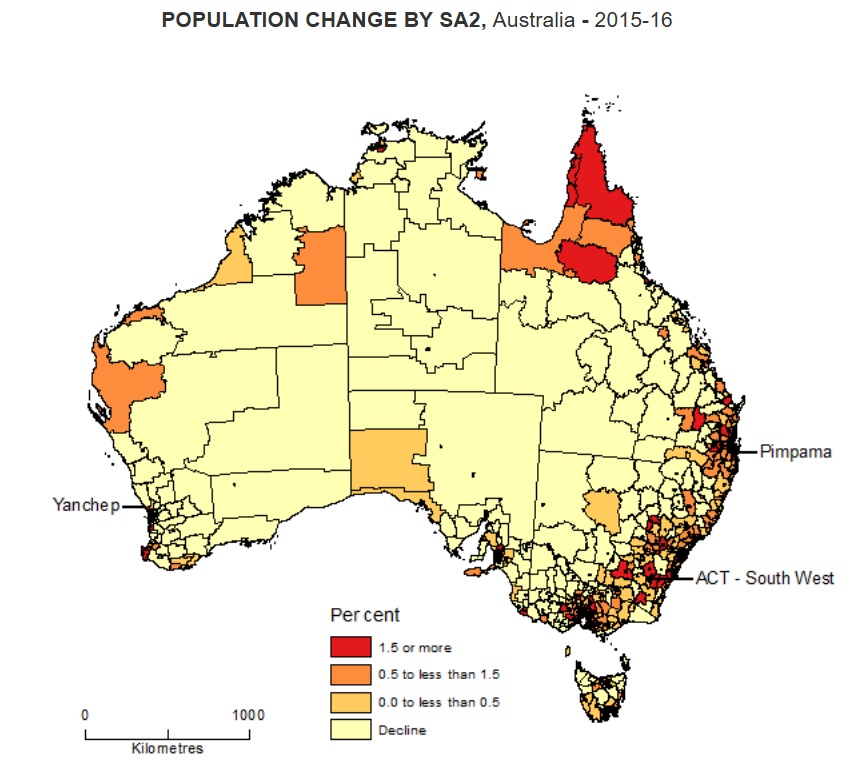

First, age varies by state and territory.

With variables like age, we often find the “typical” value by taking the median. In essence, we (statistically) line everyone up from youngest to oldest, and find the person who is older than half the population but younger than the other half.

In Tasmania, the median age among 2016 Census respondents was 42. But in the Northern Territory, it was 34. Those in Australian Capital Territory were also quite young (median age 35), whereas those in South Australia were relatively old (40).

The NT population’s relatively young age is influenced by the very high proportion that identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

While we don’t have updated estimates for that proportion (either for the NT or nationally), the data released today show that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is quite young. The median age nationally is 23. New South Wales and Queensland have the youngest Indigenous population, with a median age of 22.

This release also tells us something about the different migrant profiles across Australia. Nationally, the most common country of birth for migrants is England. And the median age of migrants is much older than for the Australian-born population (44 compared to 38).

The most common country of birth for migrants living in Queensland was New Zealand; in Victoria it was India; in NSW it was China. There may not be too many more censuses until the most common migrant nationally was not born in England.

Ahead of the forthcoming federal budget, there has been a lot of media and policy attention on housing affordability. Today’s release of census data points to some subtle differences across Australia that may influence policy responses.

Nationally, the most common tenure type is owning a three-bedroom home with a mortgage. In Queensland, however, renters make up a roughly equal share of the population. But, in Tasmania and NSW, more people own their own home outright. And in the NT, renting is the most common tenure type.

In a finding that won’t surprise many, the typical female does a bit more unpaid work around the house than the typical male. The most common category for males is less than five hours a week. The most common for females is five to 14 hours.

We won’t know how this compares to paid work for a while yet – or whether these differences vary depending on age.

What future releases will tell us

The profiles released today offer us limited information. But the census remains one of Australia’s most important datasets.

When detailed data are released in June and then progressively throughout the rest of 2017, we will be able to dig deeper into small geographic areas or specific population groups.

We will be able to ask if there are pockets of Australia with significant socioeconomic disadvantage, and if it is worsening. We will be able to hold governments accountable for the progress we have made on the education, employment and health outcomes of the Indigenous population.

And we will be able to test whether the languages we speak, the houses we are living in, and the jobs that we are doing, are changing.

But those questions rely on a high-quality census.

The attention on the 2016 Census until now has been mostly negative. There was increased concern related to data privacy, the failure of the online data entry system on census night, and staff cuts at the ABS.

In October 2016, the ABS estimated the response rate to the 2016 Census was more than 96%, and that 58% of the household forms received were submitted online. But what matters more than how many people filled in the census and how they did it is whether the responses given were accurate. We therefore need to see a lot more interrogation of the data before taking the results at face value, but we can remain cautiously optimistic.

The ABS will be hoping that now some data is released, attention will shift to what the results tell us about Australian society. It is to be hoped the data will be robust, the insights will be newsworthy, and policy and practice will shift accordingly.

We won’t know this for sure until the first major data release of data June 27 – the data released today were just a sneak peak.

Author: Nicholas Biddle, Associate Professor, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

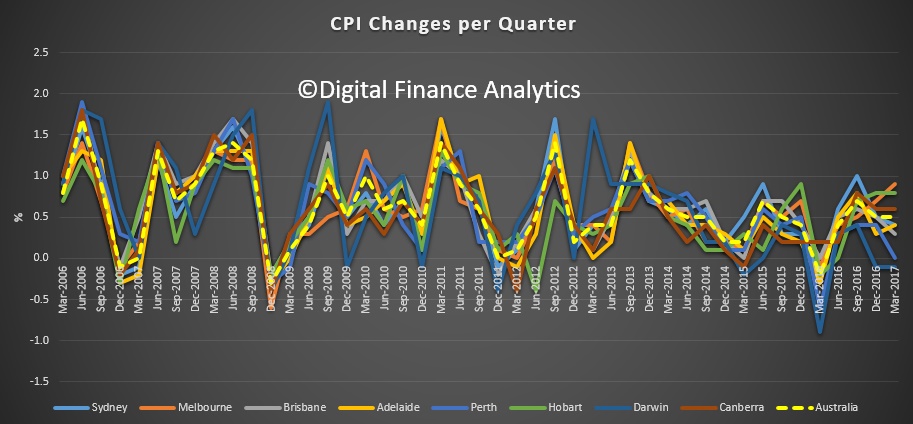

In original terms, Melbourne prices rose 0.9% in the quarter, highlighting the pressure on households there. As we said the other day, average CPI is understating what is happening in Victoria at the moment.

In original terms, Melbourne prices rose 0.9% in the quarter, highlighting the pressure on households there. As we said the other day, average CPI is understating what is happening in Victoria at the moment.

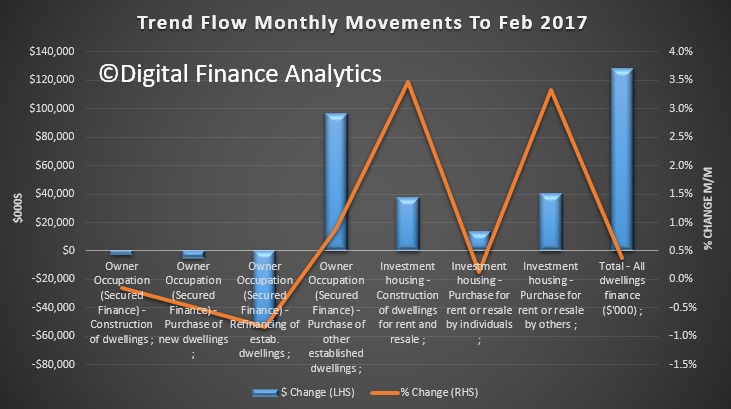

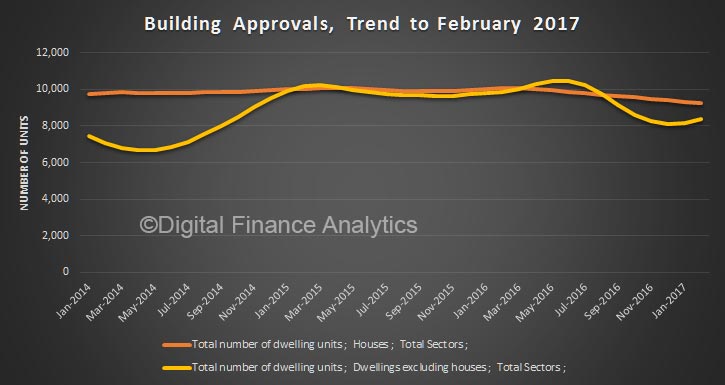

The trend estimate of the value of total building approved fell 0.1% in February and has fallen for seven months. The value of residential building rose 1.5% and has risen for two months. The value of non-residential building fell 3.3% and has fallen for six months.

The trend estimate of the value of total building approved fell 0.1% in February and has fallen for seven months. The value of residential building rose 1.5% and has risen for two months. The value of non-residential building fell 3.3% and has fallen for six months.