We know from our surveys that many households are under intense pressure thanks to rising costings of living and flat wages. Higher electricity prices are one of the main causes.

Consumers and businesses are faced with a multitude of complex offers that cannot be compared easily. Many of these issues arise from unnecessarily complex and confusing behaviour by electricity retailers.

This suggests the current Government focus on supply related issues is myopic, and this alone cannot solve the issues in the system, many of which are simply stemming from poor company behaviour. And, by the way, this mirrors the issues in the UK, where similar behaviour also exists!

The Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry preliminary report details the ACCC’s initial assessment of information it has gathered including documents and data from industry, consumers, businesses, representative groups and other government and non-government organisations.

The inquiry received over 150 submissions since it began in April. The ACCC heard directly from consumers, businesses and other stakeholders at public forums in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, and Townsville.

“It’s no great secret that Australia has an electricity affordability problem. What’s clear from our report is that price increases over the past ten years are putting Australian businesses and consumers under unacceptable pressure,” ACCC Chairman Rod Sims said.

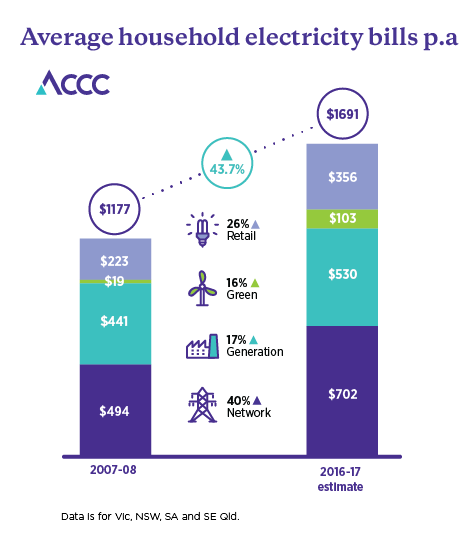

“Consumers have been faced with increasing pressures to their household budgets as electricity prices have skyrocketed in recent years. Residential prices have increased by 63 per cent on top of inflation since 2007-08.”

The main cause of higher customer bills was the significant increase in network costs for all states other than South Australia. In South Australia, generation costs represented the highest increase. There was a much larger increase in the effect of retail costs in Victoria than in other states. Retail margins increased significantly in NSW, but decreased in others.

“The main reason customers’ electricity bills have gone up is due to higher network costs, a fact which is not widely recognised. To a lesser extent, increasing green costs and retailer costs also contributed,” Mr Sims said.

“We estimate that higher wholesale costs during 2016-17 contributed to a $167 increase in bills. The wholesale (generation) market is highly concentrated and this is likely to be contributing to higher wholesale electricity prices,” Mr Sims said.

The ACCC estimates that in 2016-17, Queenslanders will be paying the most for their electricity, followed by South Australians and people living in NSW. Victorians will have the lowest electricity bills. This is due to a range of factors including usage patterns in various states, including the prevalence of gas usage in Victoria in particular.

The closure of large baseload coal generation plants has seen gas-powered generation becoming the marginal source of generation more frequently, particularly in South Australia. Higher gas prices have contributed to increasing electricity prices.

The ‘big three’ vertically integrated gentailers, AGL, Origin, and EnergyAustralia, continue to hold large retail market shares in most regions, and control in excess of 60 per cent of generation capacity in NSW, South Australia, and Victoria making it difficult for smaller retailers to compete.

The ACCC has heard many examples of the difficulties that consumers and small businesses face in engaging with the retail electricity market and the particular difficulties faced by vulnerable consumers.

“Consumers and businesses are faced with a multitude of complex offers that cannot be compared easily. There is little awareness of the tools available to help consumers make informed choices or seek assistance if they are struggling to pay their electricity bills,” Mr Sims said.

“Many of these issues arise from unnecessarily complex and confusing behaviour by electricity retailers, and in some cases this appears to be designed to circumvent existing regulation.”

“There is much ill-informed commentary about the drivers of Australia’s electricity affordability problem. The ACCC believes you cannot address the problem unless you have a clear idea about what caused it.”

“Armed with the clear findings on the causes of the problem, the ACCC will now focus on making recommendations that will improve electricity affordability across the National Electricity Market,” Mr Sims said.

Increased generation capacity (particularly from non-vertically integrated generators), preventing further consolidation of existing generation assets, and improving the availability and affordability of gas for gas fired generation, could all help to take the pressure off retail electricity bills.

The ACCC will also seek to identify ways to mitigate the effect of past decisions around network investments on retail electricity prices, noting that many past decisions are ‘locked-in’ and will burden electricity users for many years to come.

The ACCC will consider steps that can be taken to reduce complexity and improve consumers’ ability to engage with the retail electricity market and switch suppliers.

“We will provide recommendations for reform in our final report, which will be provided to the Treasurer in June 2018,” Mr Sims said.

In part based on our findings, the Federal Government has already taken some steps towards improving electricity affordability, including obtaining commitments from some retailers to move consumers off high standing offers or expired benefit offers, and the proposed removal of limited merits review of AER decisions.

In addition, the ACCC’s preliminary report contains some recommendations that could be immediately implemented by governments:

- Provide additional resourcing to the AER’s Energy Made Easy price comparison website as a tool to assist consumers in comparing energy offers

- State and territory governments should review concessions policy to ensure that consumers are aware of their entitlements and that concessions are well targeted and structured to benefit those most in need.

- Improvements to the AER’s ability to effectively investigate possible breaches of existing regulation, for example the power to require individuals to appear before it and give evidence. Consideration should also be given to the adequacy of existing infringement notices and civil pecuniary penalties to deter market participants from breaching existing regulations.

Background

The ACCC’s preliminary findings are that, on average across the NEM, a 2015-16 residential bill was $1,524 (excluding GST). This average residential bill was made up of:

- network costs (48 per cent)

- wholesale costs (22 per cent)

- environmental costs (7 per cent)

- retail and other costs (16 per cent)

- retail margins (8 per cent).

In real terms, average residential bills increased by around 30 per cent (on a dollars per customer basis) between 2007-08 and 2015-16. Average residential prices (as measured by cents per kWh measure) have increased by 47 per cent in real terms during the same period.

After considering wholesale price increases in 2016-17, the ACCC estimates that average bills in dollars per customer increased in real terms by 44 per cent since 2007-08, while prices in cents per kWh have increased in real terms by 63 per cent.

See report: Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry preliminary report

For more information: Electricity supply prices inquiry