“Paying more of your debt off while interest rates are at near record lows is a great way to take control of your debt,” says Tim Mackay, an independent financial adviser with Quantum Financial. “Interest rates will eventually start to rise and every time it happens, it’s a little more out of your pocket. The faster you pay your debt off, the less overall interest you will have to pay over the term of your loan.

Other strategies include locking in a fixed rate loan, ramping up extra payments and reducing other debt.

Wealthy feel the pinch

Affluent households – with two incomes and combined annual salaries totalling more than $150,000 – are increasingly facing financial distress because they have taken out large loans with small deposits to pay huge asking prices for real estate hotspots like Melbourne and Sydney, says DFA.

Debt of more than half the households in NSW is 4.5 times income, says Martin North, DFA principal. The national average is just under half households financing similar debt amounts.

“This is a big deal,” North says. “Especially in a rising interest rate environment. It means households have little wriggle room. Granted, many will be holding paper profits in property which has risen significantly in recent years but this does not help with servicing ongoing debt.”

Financial distress among property buyers has increased by 10 per cent over the last 12 months despite the lowest cash rates on record, according to Consumer Action, a federal government-sponsored financial counselling centre.

Property buyers say rising mortgage payments are the chief reason the family budget can’t cover all expenses.

Consumer Action claims the numbers being counselled are an “iceberg tip” of families around the nation struggling with high costs of living, underemployment, flat incomes and rising mortgage costs. The RBA estimates household debt has blown out to nearly twice annual incomes.

Questionable loans

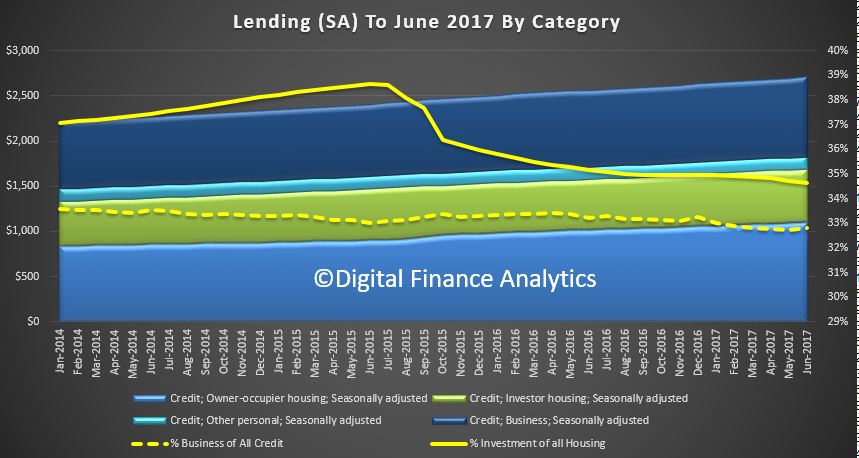

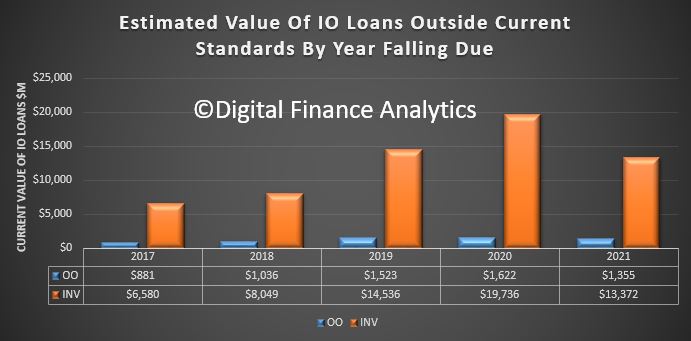

An estimated $50 billion worth of mortgages, equivalent to about 5 per cent of home loans, would fail the latest round of underwriting criteria introduced in response to regulatory pressure and growing household debt, says DFA.

Many younger buyers, typically aged 25-34 , believe home ownership has slipped beyond their reach and plan to become life-long renters, says the Grattan Institute. This is a big shift in national aspirations and retirement planning, which has traditionally assumed retirees own their homes.

Economists warn about static incomes, the highest underemployment since records began in 1978, rising out-of-cycle mortgage increases and rising property prices in the nation’s most populous states.

For example, house price growth during the past 12 months in Melbourne is nearly 22 per cent, or more than 10 times the official rate of inflation. In Canberra it is more than six times the rate of inflation and Sydney five times.

Prices are falling in Darwin and Perth but the national average is 10 per cent. The wide divergence in prices makes it harder for regulators to impose a single, national strategy.

Mortgage payments required to service the growing debt are rising as lenders respond to regulatory pressure to slow buyer demand with out-of-cycle rate rises.

Mistaken criteria

Lenders are comfortably within the 2.5 per cent buffer between the mortgage rate offered and the rate they use for affordability assessment.

But they are reviewing their assessment of household debt and capacity to repay using more sophisticated analysis of household expenditure and borrowers’ reported expenses.

Regulator the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) discovered an improbable correlation between the regulatory standard required by lenders and mortgage brokers and tens of thousands of loan applications, suggesting household expenses were being assessed to qualify for a loan, rather than meet standards.

It revealed lenders were often too generous in their assessment of borrowers’ capacity to pay because original assessments understated spending before deducting mortgage payments.

Unsurprisingly, expenses of more affluent households are significantly higher. “This helps to explain why we are seeing more affluent households getting into mortgage stress territory,” says North.

Toughest conditions in 30 years

Households are on notice that they could face some of the toughest borrowing conditions in nearly 30 years if interest rates rise 200 basis points, or eight typical rate hikes, as floated by the Reserve Bank of Australia earlier this month.

“Record low interest rates have made it possible for households to service much larger mortgages as they’ve chased rising house prices,” says Brendan Coates, a research fellow with the Grattan Institute, an independent think tank.

“Even a relatively small rise in interest rates paid by households would crimp their spending. Our research shows that if interest rates rise by just two percentage points, mortgage payments on a new home will take up more of a household’s income than at any time since the late 1980s.”

A 200 basis point rise would push the headline rate for interest rates to about 7.25 per cent.

The impact on family budgets would be equivalent to a rate of 17 per cent, the highest since Bob Hawke was prime minister.

In 1989 the Australian economy was turning from boom to bust in the wake of a global turndown and local lending excesses after deregulation of the financial sector. It was immortalised by then-Treasurer Paul Keating’s quip about a “recession we had to have” and subsequent mortgage defaults, bankruptcies and a stalled property market.

Median house price in Sydney were about $170,000 and average weekly wages around $500. Since then house prices have increased by more than six times as salaries rose by 2.5 times.

The Grattan Institute’s warning follows the RBA’s signal that the cash rate (at which it lends to commercial banks) could rise by 200 basis points to 3.5 per cent.

“With interest rates across the globe at historic lows, the risk of an interest rate rise is real,” says Coates. “And because wages are not rising fast, households are burdened by big interest payments for much longer.

“While the RBA would lift interest rates cautiously, another disruption to international financial markets like 2008 could sharply increase banks’ funding costs, raising mortgage rates.”

The analysis reveals that nearly 1000 households in Brighton, where a beachbox without electricity sells for more than $320,000, are under distress, or could face default in the next 12 months. Joe Armao, Fairfax Media.

The analysis reveals that nearly 1000 households in Brighton, where a beachbox without electricity sells for more than $320,000, are under distress, or could face default in the next 12 months. Joe Armao, Fairfax Media.