Second, while the upward trend in low Net Income Surplus (NIS) lending appears to have moderated over the past few quarters, a reasonable proportion of new borrowers have limited surplus funds each month to cover unanticipated expenses, or put aside as savings.

Third, there is only a slight moderation in the proportion of borrowers being granted loans that represent more than six times their income. As a rule of thumb, an LTI of six times will require a borrower to commit 50 per cent of their net income to repayments if interest rates returned to their long term average of a little more than 7 per cent. High LTI lending in Australia is well north of what has been permitted in other jurisdictions grappling with high house prices and low interest rates, such as the UK and Ireland.

So, APRA is finally looking at LTI and they acknowledge there are risks in the system. Better late than never…! LVR is not enough. He also discussed the non-bank sector.

It is no secret we have been actively monitoring housing lending by the Australian banking sector over the past few years. Throughout this period, our efforts have been directed at reinforcing sound lending standards in the face of strong competition that, in our view, was producing an erosion in lending quality just at a time when standards should be going in the other direction.

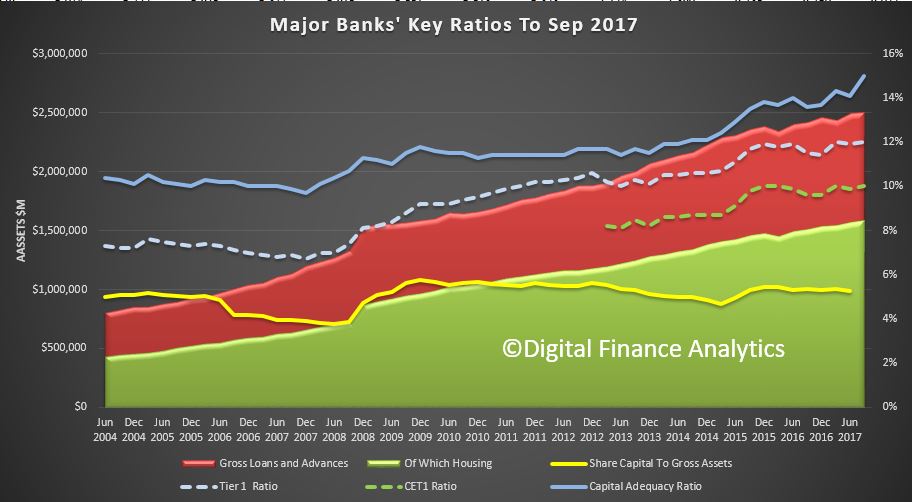

Housing loans represent over 60 per cent of total lending within the banking sector. Our goal has been to ensure APRA-regulated lenders are making sound credit decisions which are appropriate, individually and in aggregate, in the context of broader housing market and economic trends. We have consistently called out a number of factors that are contributing to an environment of heightened risk, many of which have been with us for quite some time now. Household indebtedness is high: perhaps more importantly, the trajectory is clearly for it to rise further (Chart 1).

This trend is underpinned by a sustained period of historically low interest rates, subdued income growth, and high house prices. Combined, they describe an environment in which lenders need to be vigilant to ensure their policies and practices are both prudent and responsible. In short, heightened risk requires heightened vigilance: certainly by APRA, but also – and preferably – by lenders (and borrowers) themselves.

Our activities in relation to housing broadly fit into three categories:

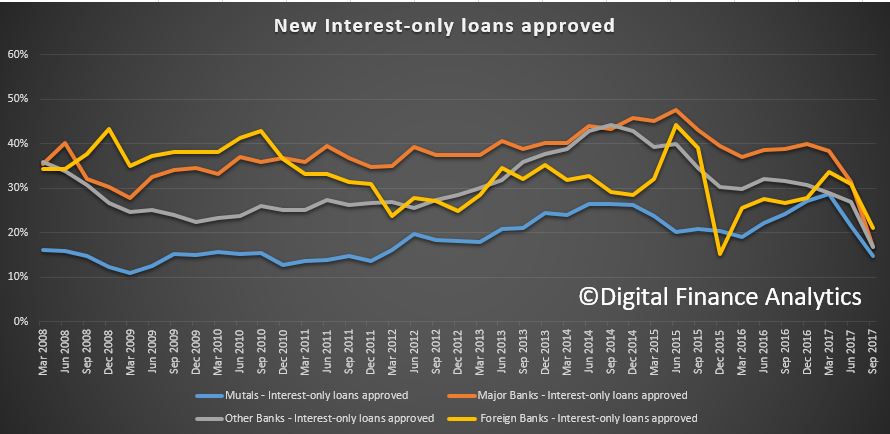

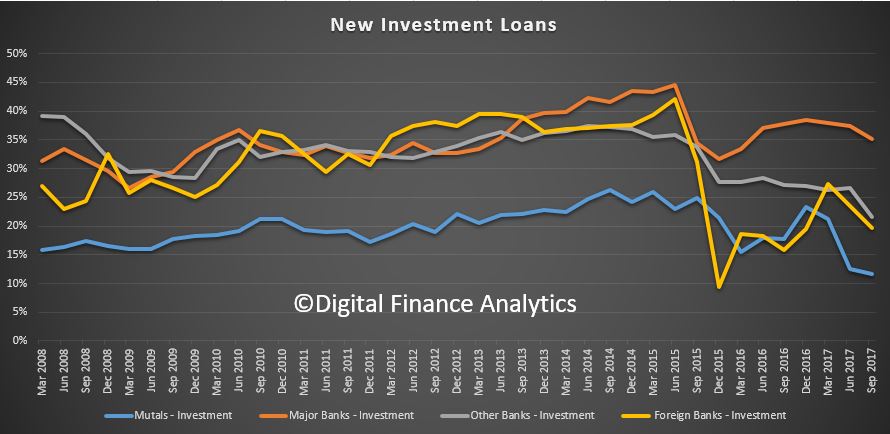

- Industry-wide portfolio benchmarks: perhaps the most-publicised of our actions have occurred at the industry level through the temporary benchmarks in place in respect of both investor lending growth and new interest-only lending. These benchmarks have served to constrain higher risk lending, and discouraged lenders from competing aggressively for these types of loans. Standards and pricing have increased as a result, tempering the growth of new credit in these areas. I’ll come back to these impacts shortly.

- Lending standards: we increased our activities in this area as far back as 2011, when we wrote to the boards of the larger authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) to seek assurance they were actively monitoring their housing portfolios and standards. In more recent years, we have also used measures such as hypothetical borrower exercises to test lending policies.2 This led to new, and in a few cases more prescriptive, regulatory guidance on appropriate lending standards and risk management in residential mortgage lending: this was first issued in 2014 and refined last year.

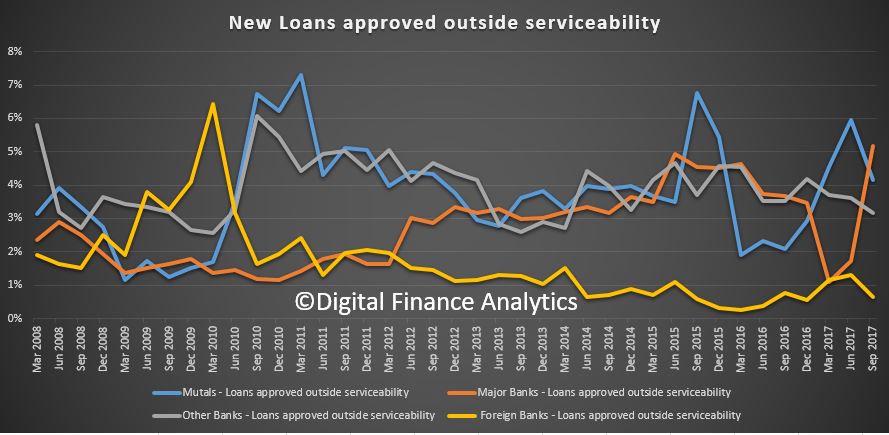

- Lending practices: as we have dived deeper into housing lending, we have increasingly focussed on actual lending practices – in other words, are lending policies reflected in the everyday conversations that lenders are having with borrowers? Sound policies only provide comfort if they are actually followed. Aided by file reviews conducted by external auditors, we have confirmed there is more to do in this area to improve serviceability measures, particularly in relation to the assessment of living expenses and the identification of a borrower’s existing debts.

In thinking about the impact of our interventions on housing credit, it’s important to note that APRA can only influence the terms and price at which credit is supplied. We cannot influence the underlying demand. Actual lending outcomes will be a product of both, so I do not want to be seen to suggest that all of the trends that I am about to discuss are solely attributable to APRA – there are many forces at play. That said, there’s no doubt many of trends are ones we hoped to see.

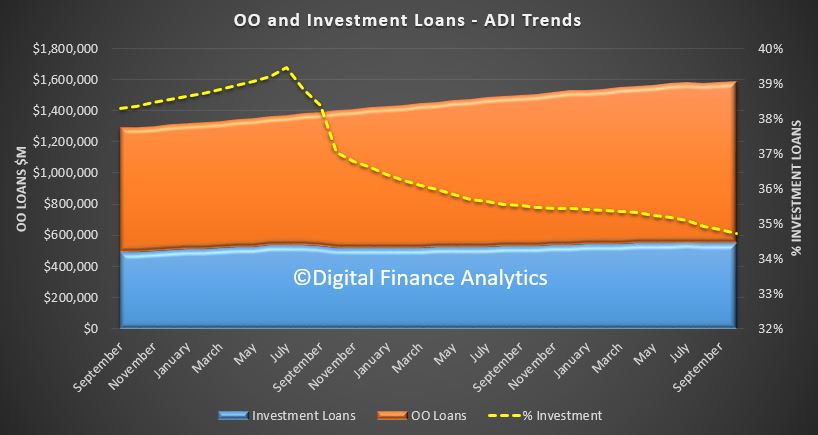

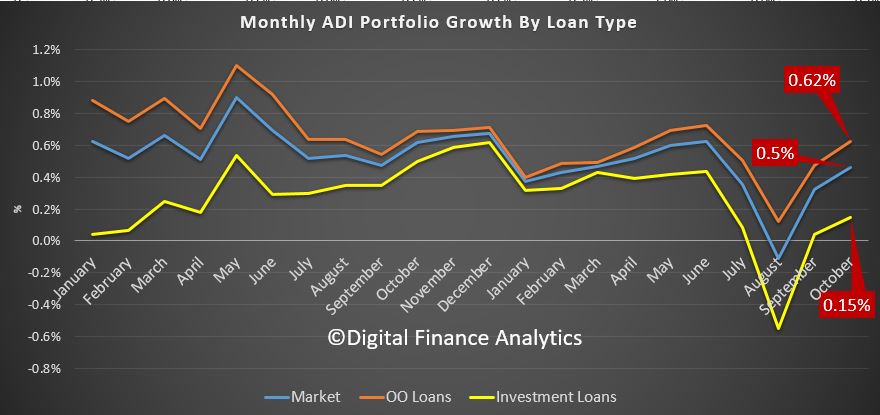

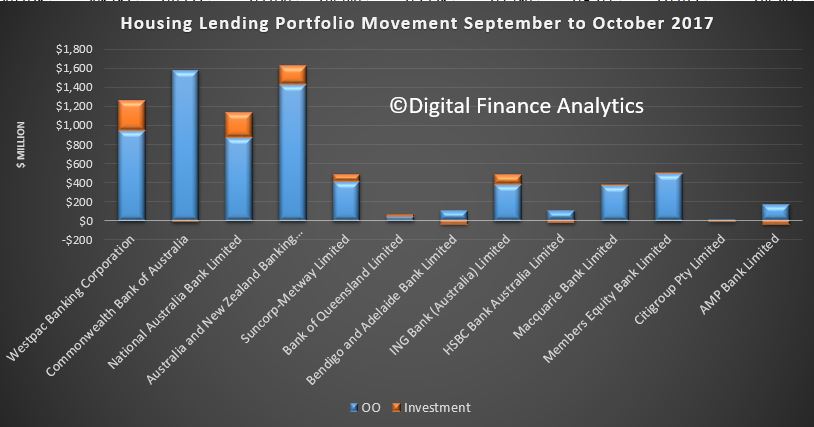

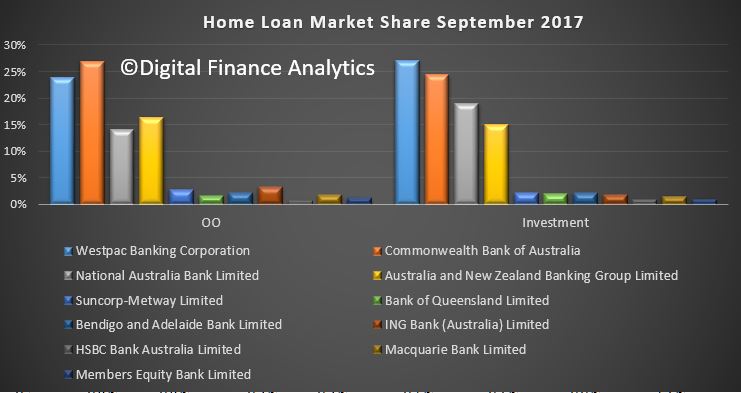

Aggregate housing credit is now growing a little over 6 per cent: not that different from its growth rate before we introduced our industry-wide investor growth benchmark in 2014 (Chart 2).

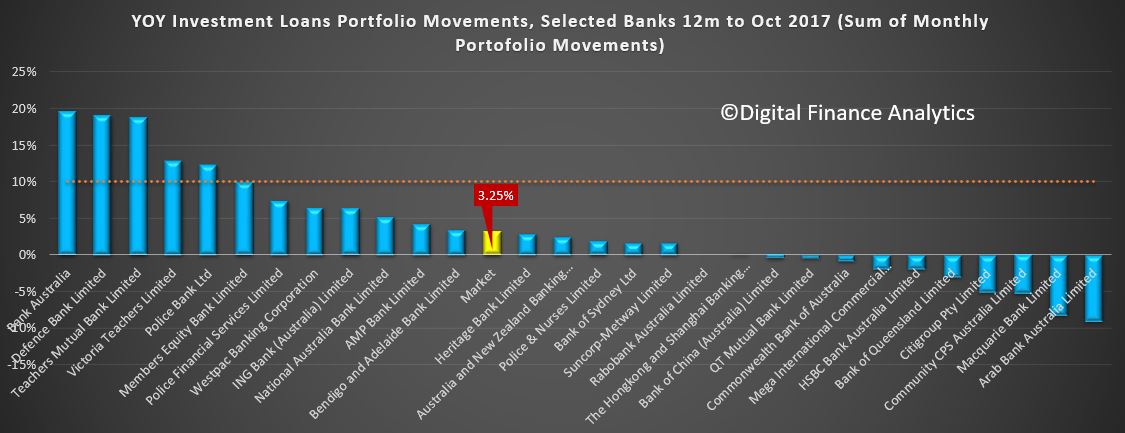

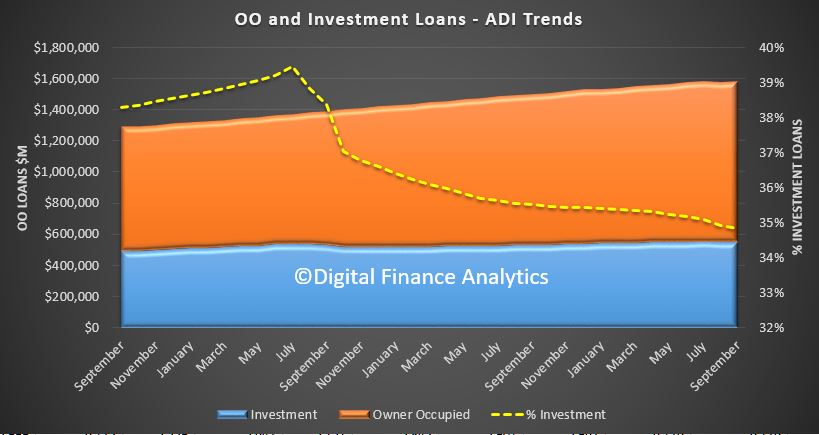

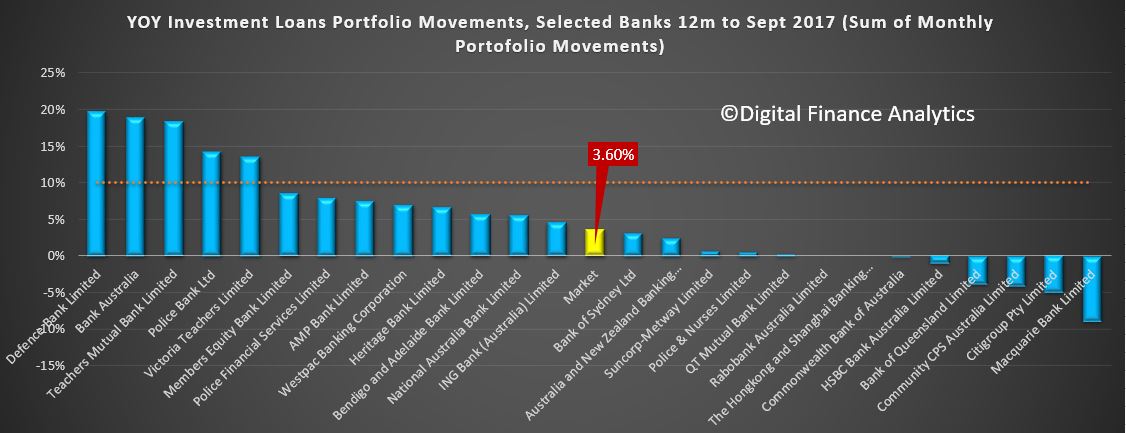

But it is clear that the strong growth in lending to investors has been curtailed. The emerging imbalance called out by the Reserve Bank in its September 2014 Financial Stability Review has been halted (although not reversed), and overall growth in credit to investors is now more in line with that to owner-occupiers. We have also had the added benefit that lenders have been forced to improve their management information systems, which in the absence of any regulatory requirements had grown lax in identifying the purpose for which money was being borrowed.

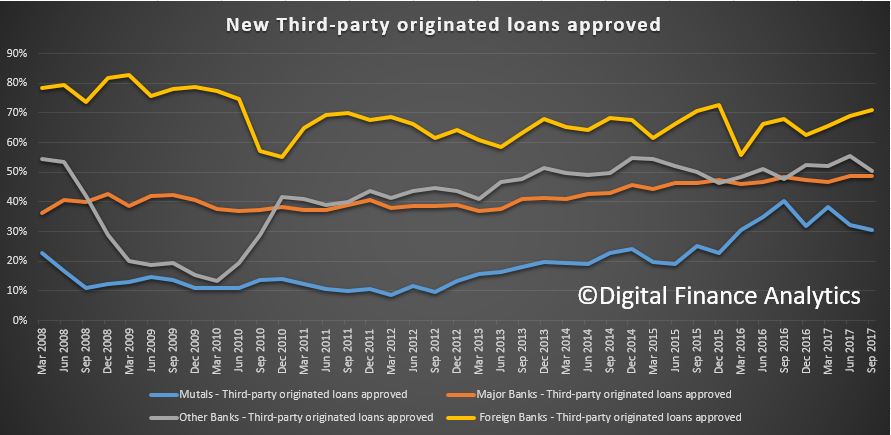

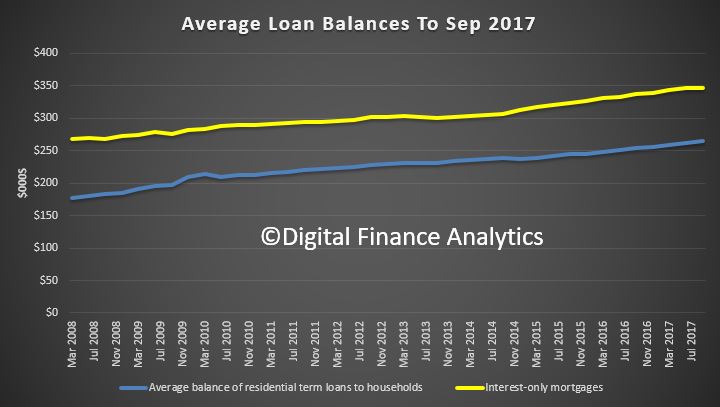

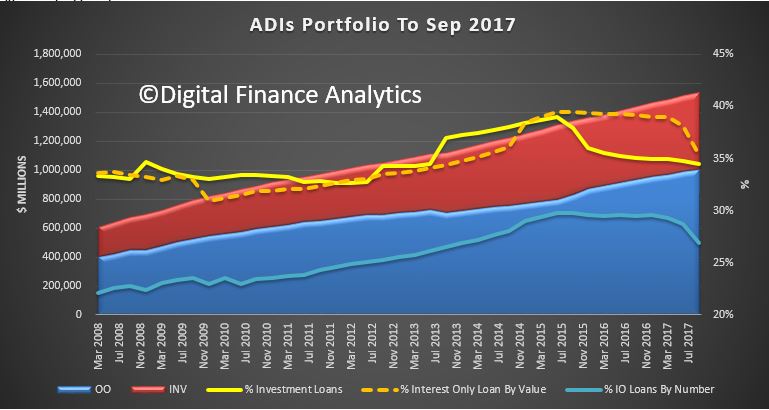

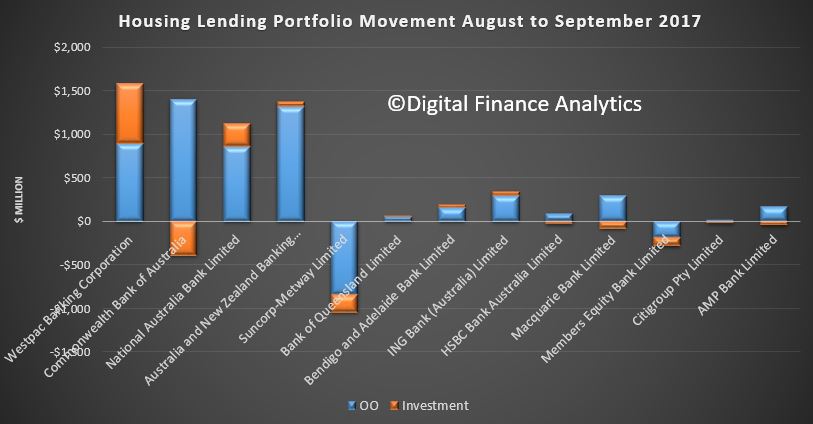

More recently, we introduced an additional benchmark with respect to new interest-only lending. The proportion of interest-only lending had been gradually building in Australia (Chart 3).

In an environment of seemingly ever-rising house prices and low interest rates, an increasing number of borrowers had become comfortable maintaining high debt levels. To exacerbate this, lenders’ practices made it easy to refinance or extend interest-only terms, making it relatively simple for a borrower to avoid paying down their principal debt over an extended period of time.

Our announcement in March this year that APRA-regulated lenders should limit their new interest-only lending to no more than 30 per cent of new lending funded during a given quarter has had an immediate and notable impact (Chart 4).

Over the past couple of years, the share of interest-only lending has moderated in response to the more modest rate of growth in lending to investors (who typically make greater use of interest-only products). Nevertheless, having run at between 40-50 per cent of new lending for some time, interest-only lending accounted for about 23 per cent of total new lending for the quarter ended September. Forecasts for the December quarter suggest something similar again.

While our focus was on new interest-only lending, the emergence of stronger price signals through differential pricing also motivated many existing interest-only borrowers to switch to principal and interest (P&I) repayments. This has resulted in a reduction in ADIs’ interest-only loans outstanding by around $36 billion, or close to 7 per cent, over the last six months. We see this switching as positive for the risk profile of loan portfolios, as it has increased the proportion of borrowers that are paying down principal on their loan and therefore working to reduce overall indebtedness.

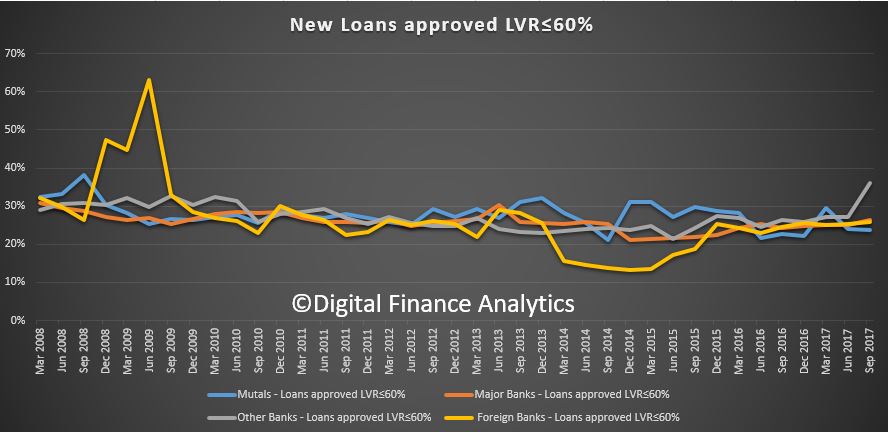

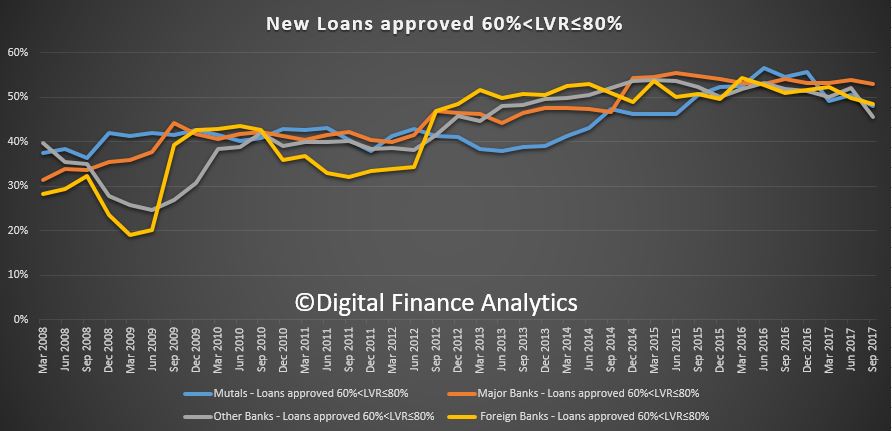

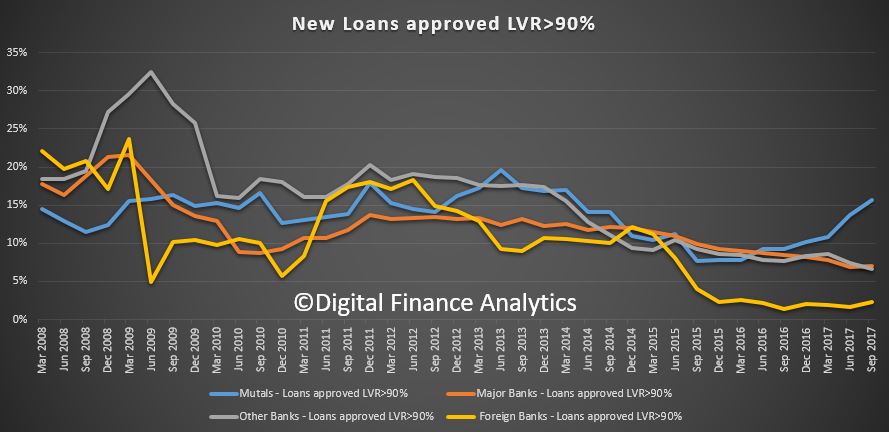

In March, we also asked ADIs to increase their scrutiny of interest-only lending with high loan-to-value ratios (LVRs). As a result, many APRA-regulated lenders reduced their maximum LVRs for interest-only loans. Over the subsequent months, we have seen a continuation in the decline of high LVR lending, both in terms of interest-only and, to a lesser extent, P&I loans (Charts 5a and 5b).

Within this broadly positive picture, however, there are a few other metrics that are continuing to track higher than intuitively feels comfortable.

First, the trend in non-performing housing loans is upward, despite a relatively benign environment for lenders (Chart 6).

With historically low interest rates and an unemployment rate that for the past few years has drifted lower, an a priori expectation might have been for non performing housing loans to return to lower levels. Certainly, the current trend is influenced by geographic factors – in particular, the softening of activity and house prices Western Australia is a significant part of the increase. But nonetheless the overall rate of non performing housing loans is drifting up towards post-crisis highs, without any sign of crisis. Given metrics of non-performing loans are a product of historical lending practices, they do not tell us anything much about lending quality today. But it does support the proposition that the need to reinforce lending standards was warranted.

With this in mind, we are paying particular attention to lending with a low net income surplus (NIS). This measure represents the lender’s assessment of the surplus income borrowers would likely have left over each month, after taking into account living expenses, debt repayments and adding in some buffers. Low NIS borrowers are obviously vulnerable to shocks. Over recent years we have been challenging lenders to ensure that their serviceability methodology is robust, and includes adequate conservatism to ensure that borrowers are not unduly exposed if their circumstances were to change. While the upward trend in low NIS lending appears to have moderated over the past few quarters (Chart 7), this chart still shows a reasonable proportion of new borrowers have limited surplus funds each month to cover unanticipated expenses, or put aside as savings.

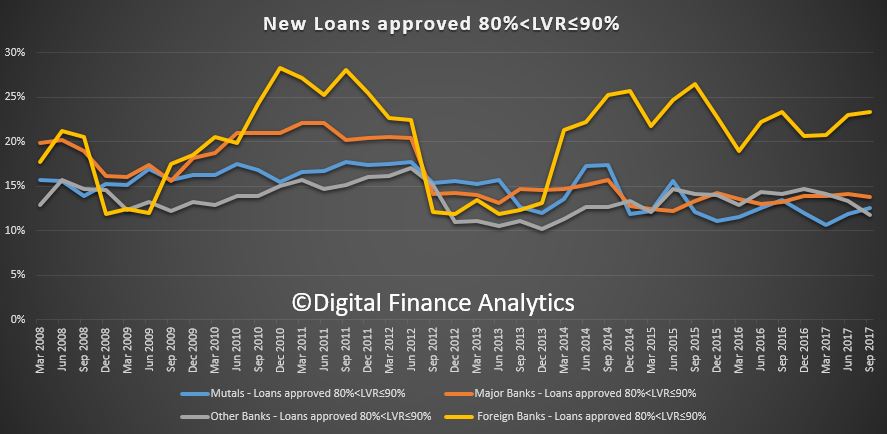

To add to this picture, we have also observed only a slight moderation in the proportion of borrowers being granted loans that represent more than six times their income (Chart 8).

As a rule of thumb, an LTI of six times will require a borrower to commit 50 per cent of their net income to repayments if interest rates returned to their long term average of a little more than 7 per cent. High LTI lending in Australia is well north of what has been permitted in other jurisdictions grappling with high house prices and low interest rates, such as the UK and Ireland.5

These last two charts are a useful segue into two key areas on which we are currently focussing.

The first is estimates of living expenses. Measures of NIS are dependent, amongst other things, on the quality of the lender’s assessments of borrower living expenses. Put simply, if living expenses are underestimated then measures of NIS are overstated. Lenders know that borrowers have difficulty estimating their expenses (and have an incentive to understate them), and so as a safeguard will typically use the higher of the borrower’s estimate and their own benchmarks of what a minimum level of living expenses is likely to be. These benchmarks are often based on the Household Expenditure Measure (HEM), with a degree of scaling for different income levels. Indeed, our recent review of lending files at some of the largest lenders provided interesting insights into the high proportion of loans that are being assessed for serviceability based on the lenders’ living expense benchmarks (Chart 9).

The use of benchmarks as the primary means of measuring living expenses operates to protect against instances of borrowers underestimating their expenditure. However, the prominent use of any type of benchmark within credit assessments only emphasises the importance of that benchmark being realistic. The HEM, for example, is a measure that reflects a modest level of weekly household expenditure for various types of families. It is open to question whether – even if it is higher than a borrower’s own estimate – such a benchmark always provides a realistic assessment of a borrower’s genuine expenditure needs. From APRA’s perspective, we would like to see the industry devote more effort to the collection of realistic living expense estimates from borrowers and give greater thought to the appropriate use and construct of benchmarks in instances where those estimates are deemed insufficient.

The second key area is lenders’ knowledge of a borrower’s financial commitments and total indebtedness. Loan-to-income ratios (LTI) provides a measure of the extent to which borrowers are leveraged, but are obviously limited because they do not capture the borrower’s total debt level. Many other countries have used credit scores and positive credit reporting for some time as a means of sharing information and conducting comprehensive credit assessments. In Australia, other financial commitments remain something of a blind spot for lenders. However, the Government’s recent announcement of mandatory comprehensive credit reporting beginning from next year will facilitate a switch from LTI to debt-to-income (DTI) metrics, and strengthen credit assessments and risk management. This will undoubtedly be a positive development for the quality of credit decisions.

We are working within a system in which well north of 90 per cent of housing finance is currently provided by APRA-regulated lenders. So the measures that we have taken impact the vast majority of mortgage lending in Australia. But when the flow of credit encounters regulation, it’s like flowing water encountering a barrier: one tries to find a way around the other. We therefore haven’t been blind to the fact that the more we lift the quality and/or reduce the quantity of lending in the regulated sector, the more that it provides opportunity for non-APRA regulated lenders to fill any unsated demand. We need to be mindful that, while from a financial safety (microprudential) perspective credit portfolios of individual regulated lenders will be improving, from a financial stability (macroprudential) perspective the risk may just be moving elsewhere. Moreover, it could be concentrating risk in the parts of the system that are less transparent or receive less regulatory scrutiny – often short-handed as the ‘shadow banking’ sector.

There have been two main responses to this risk in recent times:

- First, we have been looking at whether bank funding of housing loans via warehousing facilities is facilitating risks that would be materially higher than banks would naturally want to write for themselves. In other words, we want to make sure lenders have not been pushing risk out the front door, only to bring it in again via the back. Warehouse exposures are relatively small, but we have observed that there is quite a high tolerance for investor and interest-only loans within warehouses – in some cases, documented eligibility criteria allow for as high as 60 per cent of the pool in each of these categories. Across the industry, non-ADI lenders utilising ADI warehouses would seem to have, on average, slightly higher risk profiles in their portfolios, but there are clearly some individual non ADIs lenders with lending portfolios that are dominated by the sorts of lending that we have been disincentivising ADIs from taking on.

- Secondly, the Government has introduced legislation into Parliament that would provide us with a new power to use should we think the aggregate impact of non-ADI lenders is materially contributing to risks of instability in the Australian financial system.

I would like to say a few words about this power, since I know it has generated quite a bit of interest amongst many in this room. The first point I would make is to stress that we see it very much as a reserve power. There is a clear threshold to be met before any rules could be applied to non-ADI lenders: that (i) APRA considers that the lending by non-ADI lenders contributes to risks of instability in the Australian financial system and, (ii) APRA considers that it is necessary, in order to address those risks, to make rules covering the lending of non-ADI lenders.

That means that, most of the time, the power to impose rules will lie dormant: non-ADI lenders will go about their business as they have always done, unconstrained by any APRA rules. Importantly, non-ADI lenders will not be subject to any day-to-day prudential oversight by APRA. For those of you uncomfortable at the thought of APRA supervising non-ADIs, let me assure you the feeling is mutual. We are not seeking to expand our supervisory remit and, beyond collecting information that allows us to track aggregate trends in lending activity, we will not be undertaking any supervision of individual lenders. Indeed, we are keen to distance ourselves from any perception we are responsible for the activities of any individual non-ADI lender, or for protecting their investors. To be absolutely clear, we have no intention of taking on that role. For investors in non-ADI lenders, market discipline and caveat emptor remain the primary regulating influences. Our focus is very much on the aggregate.

The ASF’s submission on the proposed legislation noted that any judgement on the extent of material risks to financial stability is fraught with difficulty. I wholeheartedly agree. There is no single measure of financial stability: it is necessarily a matter of judgement, taking into account a wide range of factors. But we will undoubtedly be better placed to make good judgements if we have good data. So the new legislation does impose a new set of ongoing requirements for those businesses that exceed the size threshold to be registered under the Financial Sector (Collection of Data) Act 2001 (FSCODA), and hence provide data to APRA to help us track overall lending trends. We are giving thought to what that data might entail, and will consult with the industry before any new requirements are introduced. But as per the ASF’s submission, we will mainly be seeking to observe the volume and nature of lending that is occurring, and not the traditional prudential metrics that we collect from ADIs.

The ASF’s submission also noted that the new legislation might create some uncertainty in the minds of investors as to the regulatory framework applying to non-ADI lenders. I cannot dispute that might be the case, although clarifying that non-ADIs will not be prudentially supervised and that APRA’s rule-making is a reserve power should alleviate some of those concerns. But equally, given international perceptions of Australia’s housing market, reinforcing the understanding of international investors that the Australian authorities have a wide range of tools at their disposal to support financial stability, should the need arise, certainly offers benefits as well.

As to what would happen if we got to a point where we thought the introduction of non-ADI rules might be needed, it is important to note that, as with data collections, we would need to undertake a consultation process, engaging with affected lenders on what we proposed to do in response to the risks we perceived to exist.

Let me finish on this issue by noting that, as things stand today, we do not foresee the need for any new non-ADI lender rules to be introduced the moment the legislation is passed. Our immediate priority will be to consider how to identify the right entities to collect data from, and the data we want to collect. We look forward to a constructive engagement with the industry on those matters