From Mortgage Professional Australia.

There are two ways to bury bad news, and brokers have now experienced both. Method one is to run that news on a Friday when everyone’s mind is on the weekend, as APRA did when announcing curbs on interest-only lending on the final day of March. The 2017 Federal Budget took the other approach: burying bad news in more news, namely a controversial $6.2bn bank levy.

Whether increased regulation of non-banks is indeed ‘bad news’ is up for interpretation. Yet for an industry so jaded by regulation, the announcement that APRA will now have oversight of non-bank lenders – who were previously regulated by ASIC – has occurred with remarkably little in the way of reaction.

“Of all the things that were announced, that’s the biggest deal,” Martin North, principal of consultancy Digital Finance Analytics told MPA. “If APRA now has responsibility for them, they will have to make a decision about whether they require them to hold capital, which is probably not going to happen as they aren’t ADIs … but they will probably put a structure, or limits, or some other mechanism to reduce the risky lending behaviour.”

A work in progress

With just three paragraphs in hundreds of pages of budget papers, there’s little in the way of specific information on the new regulations. It has now been confirmed that the government will provide an extra $2.6m over four years to APRA to “exercise new powers” and collect data from non-authorised deposit-taking institutions. To assist with this the Banking Act of 1959 will be modernised, also enabling APRA to restrict lending to certain geographical areas.

Appearing before the Senates Estimates Committee in late May, APRA chairman Wayne Byres was pushed for more information on APRA’s role. Byres played down the degree of regulation. “If there is a systemic risk … APRA would have the capacity to introduce some rules which might help mitigate that. But that is very different to saying we take day-to-day responsibility for individual institutions.”

Nevertheless, uncertainty remains. Asked by Liberal senator David Bushby which institutions would be affected by APRA’s expanded powers, Byres was unable to provide an answer, as the government had yet to announce the actual powers APRA would have.

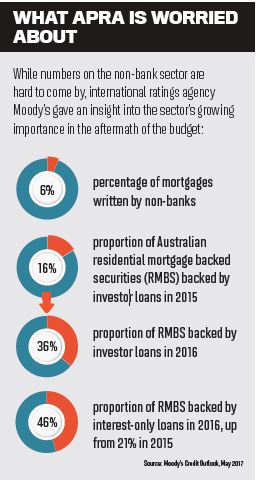

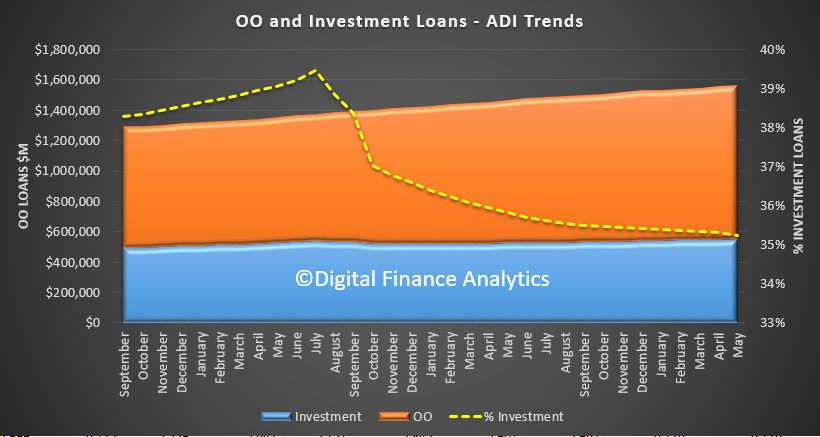

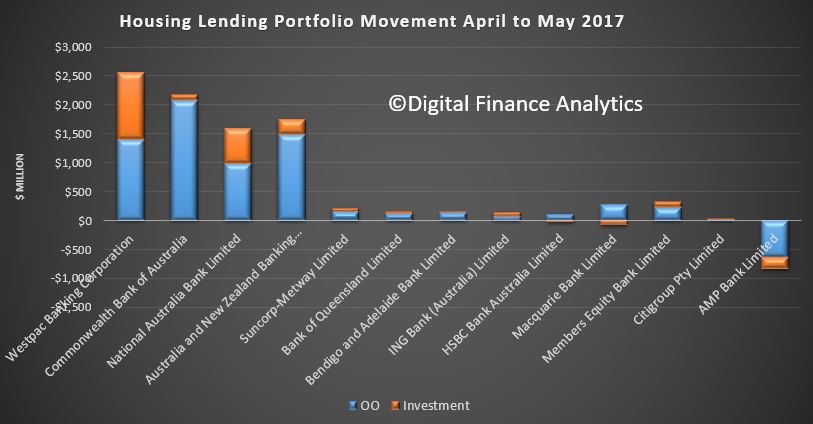

Byres was more specific about why the new powers were required. It was “in some sense” a consequence of restricting lending by ADIs to investors, which Byres suspected had pushed a large degree of investor lending into the nonbank sector. While Byres said the failure of individual non-banks was “a fact of life”, a build-up of risky lending in the sector could have more far-reaching consequences.

Investor and interest-only caps

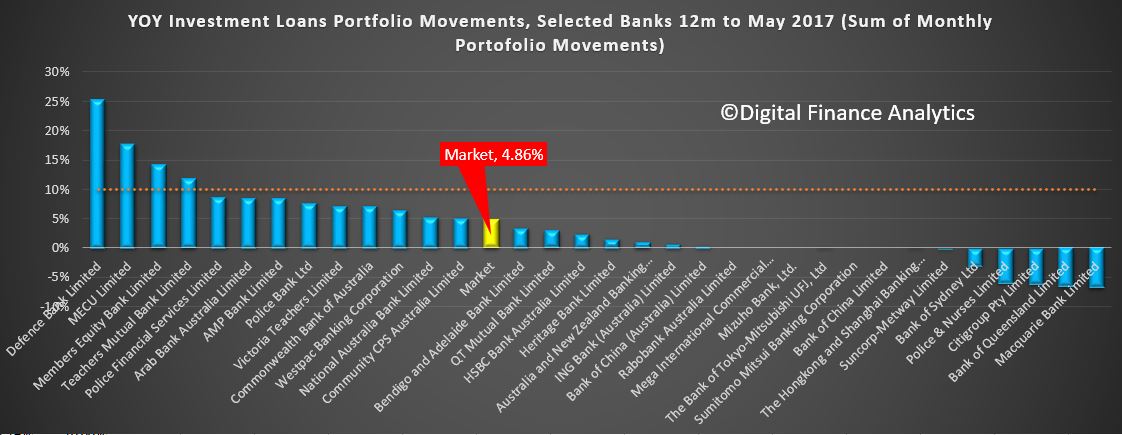

Byres’ inability to specify APRA’s new powers (at the time of writing) leaves open the possibility of APRA capping investor and interest lending growth by non-banks at the same level as banks. At present, growth per lender is capped at 10% and 30% respectively.

APRA warned ADIs in March that lending by non-banks they fund “should not be growing faster than their own portfolio or materially faster than their own portfolio and also should be of a similar quality to loans they would be prepared to write themselves”, Byres told the Senate Estimates Committee.

Having experienced rapid investor lending growth from a small base, many non-banks would be hit hard by a percentage-based limit. In a furious article in Australian Broker magazine, ex-Pepper CEO Patrick Tuttle warned against “regulating the non-bank sector out of existence”, as well as depriving legitimate borrowers of funds and causing a sharp correction in house prices. Tuttle also claimed that non-banks had not been consulted by the Treasurer prior to the announcement.

The non-bank lenders MPA spoke to appeared to be unconcerned by the prospect of APRA oversight. Pepper Money said it was “business as usual”, claiming it had already taken note of APRA regulation of ADIs to ensure a balanced approach to lending, in addition to satisfying the demands of warehouse funders. Liberty CEO James Boyle supported the regulator’s efforts to lessen the risk of an inflated property market. Boyle argued that, with limited scale compared to the majors, non-banks already had to build balanced portfolios with diverse geographies, products and borrower types.

However, Boyle said, “as non-banks do not accept deposits, there is less need to apply measures primarily designed for depositors”. According to Boyle, the “very virtue of their difference” allows the non-bank sector to increase competition in the industry, providing better choice for customers. “We would say the government should continue to be sensitive with moves such as those proposed to not increase costs for consumers, stifle competition or shift responsibility for risk management from the regulated to the regulator.”

In MPA’s Brokers on Non-Banks survey, which will be published in August, hundreds of brokers were asked whether they’d continue using non-banks if they were regulated in the same way as banks.

The majority of brokers said they would, pointing out other advantages the non-banks have over the majors. As one Sydney broker explained, “they are proactive, adept and keen for business. Their hunger means that they meet the market and fill the niches the major lenders don’t”.

However, many brokers warned that already-high interest rates would become impossible to justify without correspondingly differing policies. “If non-banks were restricted by APRA, then likely their policy attractiveness would be lost,” commented a broker from Perth, “so the reasons to use them would be less. However, maybe they would keep their upfront approach, which I prefer to the majors’ ‘have to haggle to get a good deal’ approach.”

For decades non-banks have been trying to catch the eyes of consumers and brokers. Australia is only just beginning to wake up to its ‘shadow banking sector’, as Byres found at the Senate when he had to explain that shadow banking was “not illegal banking”. As APRA gradually elaborates on what ‘oversight’ really means, non-banks may discover their newfound popularity with investors is a double-edged sword.