Wayne Byers spoke at The American Chamber of Commerce in Australia Business Briefing on International standards and national interests.

He described the current state of play with Basel III:

He described the current state of play with Basel III:

Although the core components of Basel III – a strengthening of the framework for bank capital, liquidity and funding – was agreed in 2010, the final points of detail still remain to be agreed. This is frustrating for regulators and banks alike. A decade on from the onset of the financial crisis, I don’t think anyone could say it is being rushed! And with a number of bank failures just in recent weeks in Canada, Italy and Spain, at a time when economic conditions are not particularly volatile, I also don’t think anyone could say the need to be vigilant about strengthening the financial system has diminished.

Although the finishing line for Basel III is in sight, we still haven’t yet found the alignment of interests that will allow the drafters to put down their pens and publish the final version. What is at the heart of the delay? Ultimately, it is the difficulty in aligning national interests with the common good. To have a common standard, all jurisdictions – and there are 27 of them at the Basel Committee table, represented by 45 individual agencies, who operate by consensus – are essentially agreeing to give up some degree of freedom as to their own domestic standard-setting. In many cases, this won’t be problematic since – as I will come back to in a minute – the minimum standard produced around the table in Basel will be lower than one would want to apply domestically. But in others it may involve a genuine trade-off between domestic considerations and the benefits of consistent international practice. Those trade-offs can be hard, even for experts, to measure and assess, let alone explain to non-experts.

The good news, though, is that the effort to find agreement continues. And it was pleasing to see the US Treasury, in its first report in response to the President’s Executive Order on financial regulation, acknowledge that ‘U.S. engagement in international financial regulatory standard-setting bodies remains important’3 and that it ‘supports efforts to finalize remaining elements of the international reforms at the Basel Committee…to strengthen the capital adequacy of global banks.’4 At a time when there is genuine concern about the potential for fragmentation of global financial markets, such statements can only be welcomed.

Nevertheless, I think the current work in Basel will largely mark the end of the cycle, and we are largely done when it comes to major new international standards.

But the question is how to implement locally. In Australia he says

APRA does not see any case for implementing a domestic regulatory framework that is less robust than the international norms. Australia cannot simultaneously rely more than most on cross-border funding, and seek to be exempted from some or all of the regulatory requirements applying in other parts of the world. In any event, even if we attempted to implement a weaker set of domestic rules, international markets and counterparties would hold Australian banks to the international standards and measures anyway. So we see little value in trying to stand apart from the rest of the world, claiming to know better.

But it is also true that international standards are not always settled in the exact form that we would prefer if we had complete freedom to write the rules ourselves. We have a seat at the table, and seek to use our influence to shape the final form of any agreement, but compromise is inevitably necessary.

And the standards should be higher than the minimum:

…even within international standards, there are often areas in which national discretion is granted. That is, the standard allows a choice, usually on narrow technical issues, that is deliberately and explicitly left to the domestic authority. In these cases, we can make a decision we think works best for Australian circumstances and, regardless of the decision taken, still be seen as in compliance with the international standard.

But the most important factor in balancing international standards and national interests is that, at least in the financial regulatory world, international standards are minimum standards. It is quite open to us to improve upon them, reflecting our own circumstances. In Australia, we have long taken the view that we should aspire to a higher standard of safety than provided by solely adhering to minimum Basel standards. In part that reflects the nature of our highly concentrated banking system, and also the lack of pre-funded deposit insurance. We seek to ensure that Australia’s banking system is considerably more resilient than has generally been the case for international banking in recent decades. It is all too evident that the incidence of banking crises has been too frequent, their costs have been extraordinarily high, and many communities around the world are still wearing the consequences. We think we should try to do better.

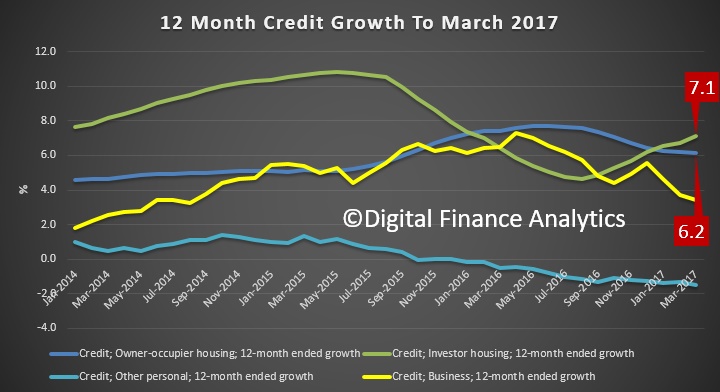

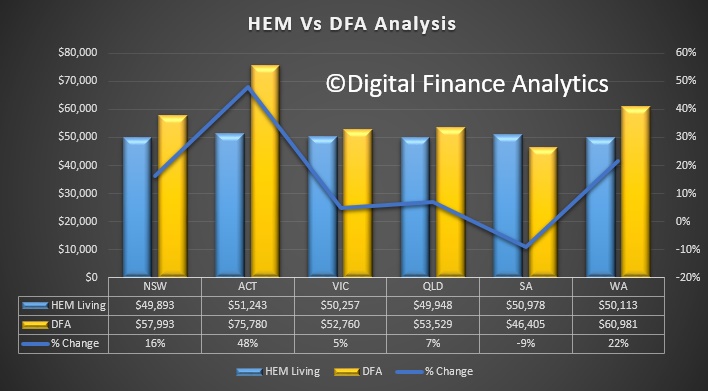

So this leaves the door firmly open for higher capital ratio in the approach which we expect soon. Worth remembering that every 1% uplift on capital for the majors costs around $15bn, or slightly more. We think it is likely the majors will be required to hold more capital, either by way of a counter-cyclical buffer, or a change to the DSIB buffer. We also think mortgage risk weights may continue to rise.

Any change will put further upward pressure on mortgage interest rates. Worth too reflecting on the UK announcement, we covered this morning, there the Bank of England is lifting the counter-cyclical buffer by 1%, half now and half in November!