Wayne Byers APRA Chairman spoke at CEDA’s 2017 NSW Property Market Outlook in Sydney today. Of note, he explains the reason why the 10% investor speed limit was not reduced, because of the potential impact on commercial propery construction!

My remarks today come, unsurprisingly, from a prudential perspective. Property prices and yields, planning rules, the role of foreign purchasers, supply constraints, and taxation arrangements are all important elements of any discussion on property market conditions, and I’m sure the other speakers today will touch on most of those issues in some shape or form. But I’ll focus on APRA’s key objective when it comes to property: making sure that standards for property lending are prudent, particularly in an environment of heightened risk.

Sound lending standards

Our recent activity in relation to residential and commercial property lending has been directed at ensuring banking institutions maintain sound lending standards. Our ultimate goal is to protect bank depositors – it is, after all, ultimately their money that banks are lending. Basic banking – accepting money from depositors and lending to sound borrowers who have good prospects of repaying their loans – is what it’s all about. Of course, banking is about risk-taking and it is inevitable that not every loan will be fully repaid, but with appropriate lending standards and sufficient diversification, the risk of losses that jeopardise the financial health of a bank – and therefore the security offered to depositors – can be reduced to a significant degree. The banking system is heavily exposed to the inevitable cycles in property markets, and our goal is to seek to make sure the system can readily withstand those cycles without undue stress.

Our mandate goes no further than that. We also have to take many influences on the property market – tax policy, interest rates, planning laws, foreign investment rules – as a given. And there are credit providers beyond APRA’s remit, so a tightening in one credit channel may just see the business flow to other providers anyway. For those reasons, there are clear limits on the influence we have. Property prices are driven by a range of local and global factors that are well beyond our control: whether prices go up or go down, we are, like King Canute, unable to hold back the tide.

Of course, that is not to ignore the fact that one determinant of property market conditions is access to credit. We acknowledge that in influencing the price and availability of credit, we do have an impact on real activity – and this may feed through to asset prices in a range of ways. But I want to emphasise that we are not setting out to control prices. Property prices will go up and they will go down (even for Sydney residential property!). It is not our job to stop them doing either of those things. Rather, our goal is to make sure that whichever way prices are moving at any particular point in time in any particular location, prudentially-regulated lenders are alert to the property cycle and making sound lending decisions. That is the best way to safeguard bank depositors and the stability of the financial system.

Residential property lending

APRA has been ratcheting up the intensity of its supervision of residential property lending over the past five or so years. Initially, this involved some fairly typical supervisory measures:

- in 2011 and again in 2014, we sought assurances from the Boards of the larger lenders that they were actively monitoring their housing lending portfolios and credit standards;

- in 2013, we commenced more detailed information collections on a range of housing loan risk metrics;

- in 2014, we stress-tested around the largest lenders against scenarios involving a significant housing market downturn;

- also in 2014, we issued a Prudential Practice Guide on sound risk management practices for residential mortgage lending; and

- we have conducted numerous hypothetical borrower exercises to assess differences in lending standards between lenders, and changes over time.

These steps are typical of the role of a prudential supervisor: focusing on the strength of the governance, risk management and financial resources supporting whatever line of business is being pursued, without being too prescriptive on how that business should be undertaken.

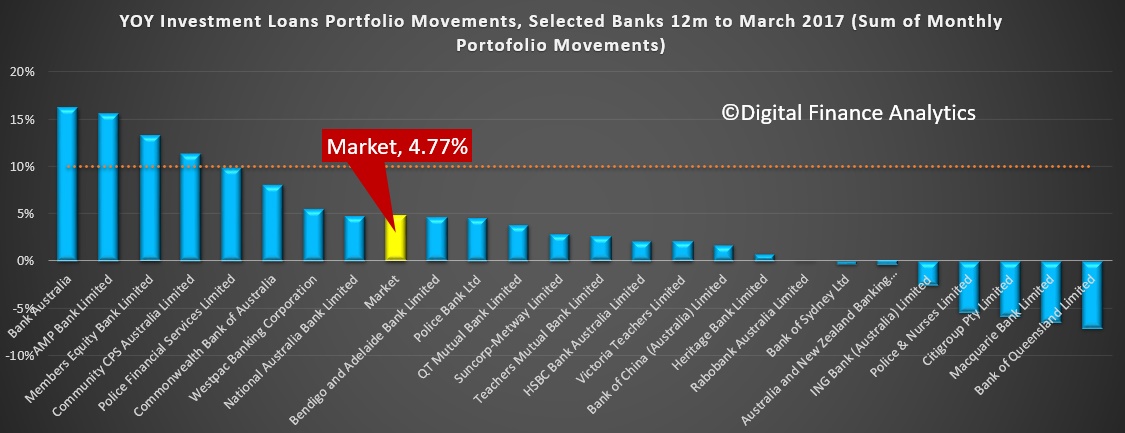

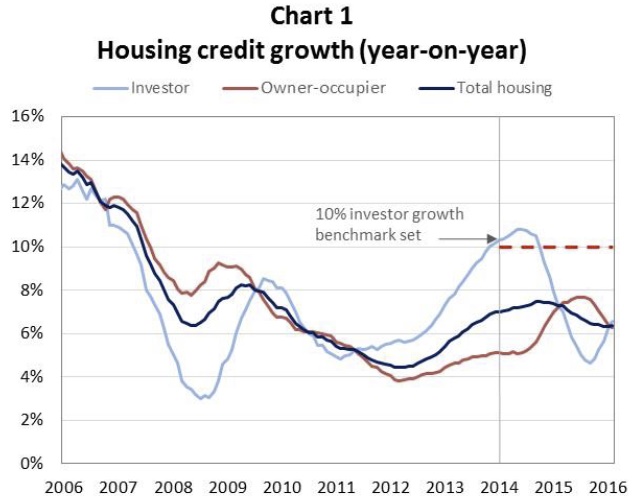

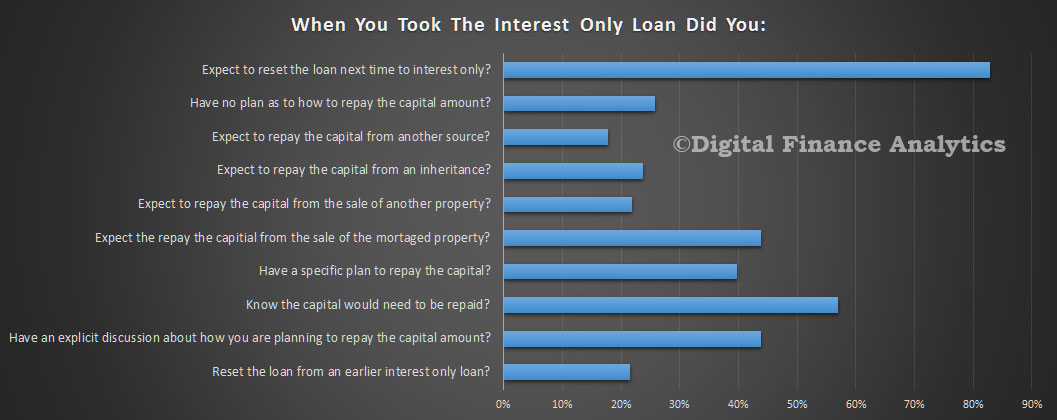

But from the end of 2014, we stepped into some relatively new territory by defining specific lending benchmarks, and making clear that lenders that exceeded those benchmarks risked incurring higher capital requirements to compensate for their higher risk. In particular, we established quantitative benchmarks for investor lending growth (10 per cent), and interest rate buffers within serviceability assessments (the higher of 7 per cent, or 2 per cent over the loan product rate), as a means of reversing a decline in lending standards that competition for growth and market share had generated.

I regard these recent measures as unusual, and not reflective of our preferred modus operandi. We came to the view, however, that the higher-than-normal prescription was warranted in the environment of high house prices, high household debt, low interest rates, low income growth and strong competitive pressures. In such an environment, it is easy for borrowers to build up debt. Unfortunately, it is much harder to pay that debt back down when the environment changes. So re-establishing a sound foundation in lending standards was a sensible investment.

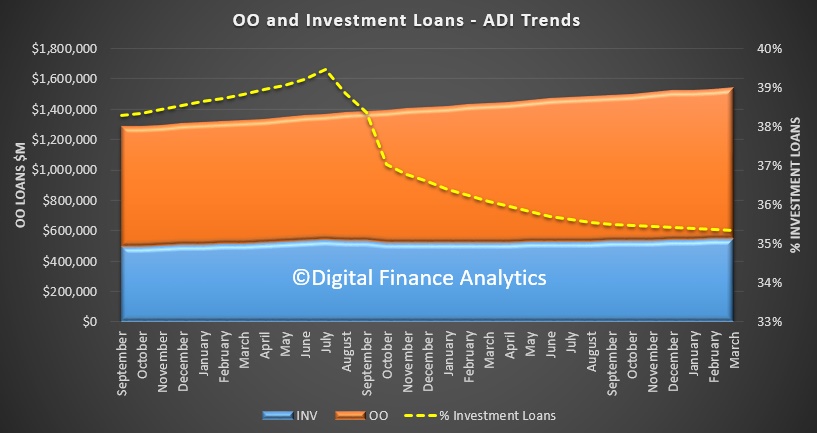

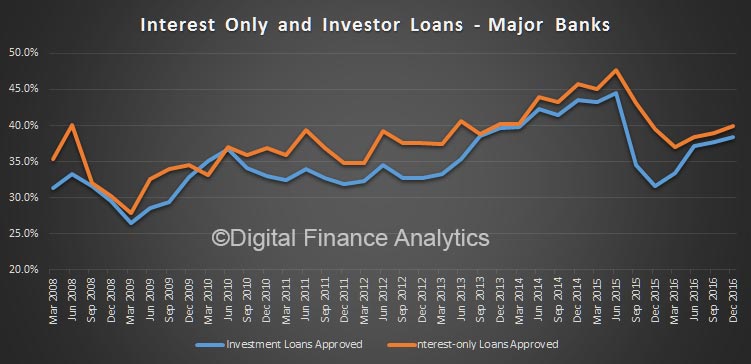

Since we introduced these measures in late 2014, investor lending has slowed and serviceability assessments have strengthened. But at the same time, housing prices and debt have got higher, official interest rates have fallen further and wage growth remains subdued. So we recently added an additional benchmark on the share of new lending that is occurring on an interest-only basis (30 per cent) to further reduce vulnerabilities in the system.

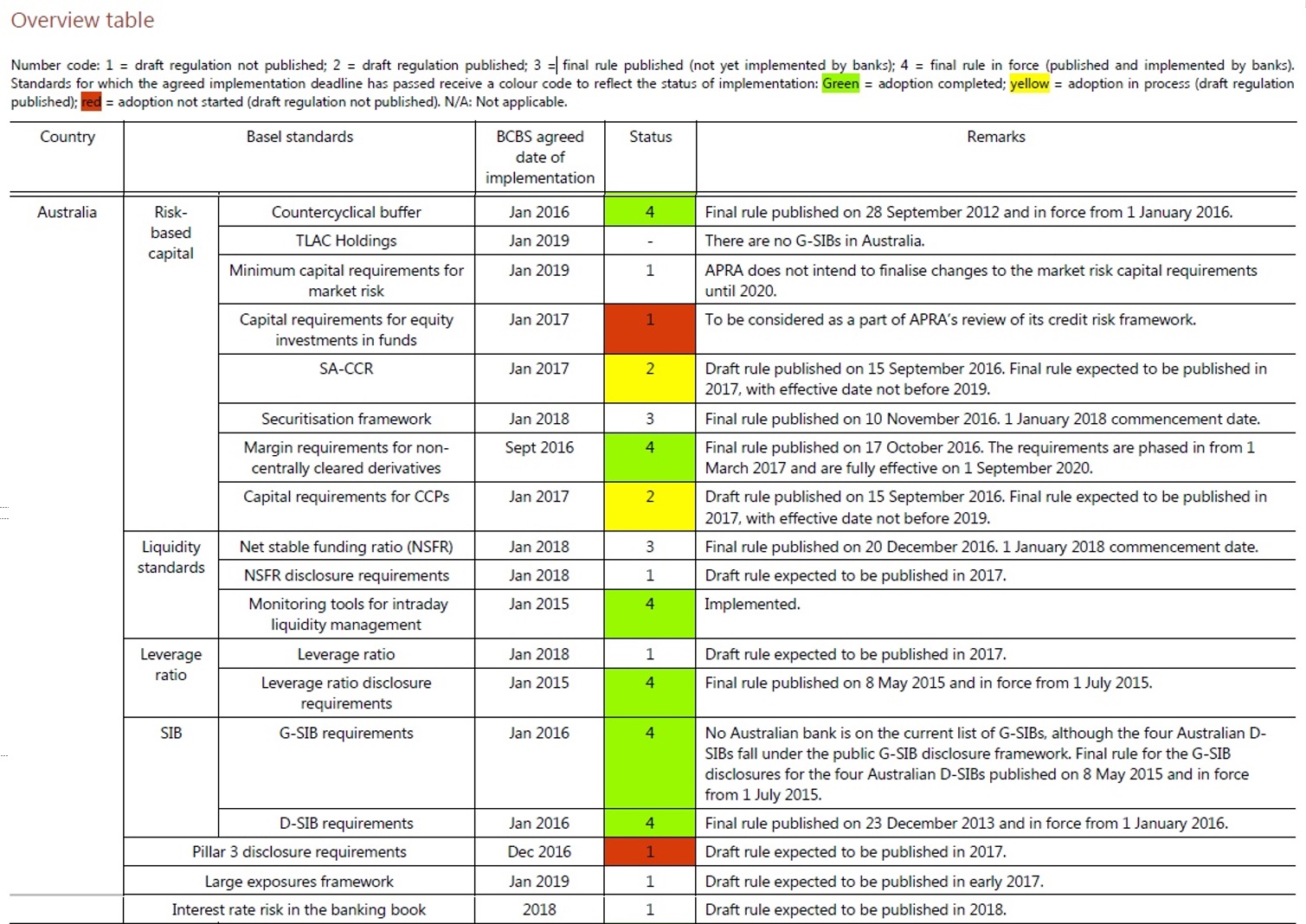

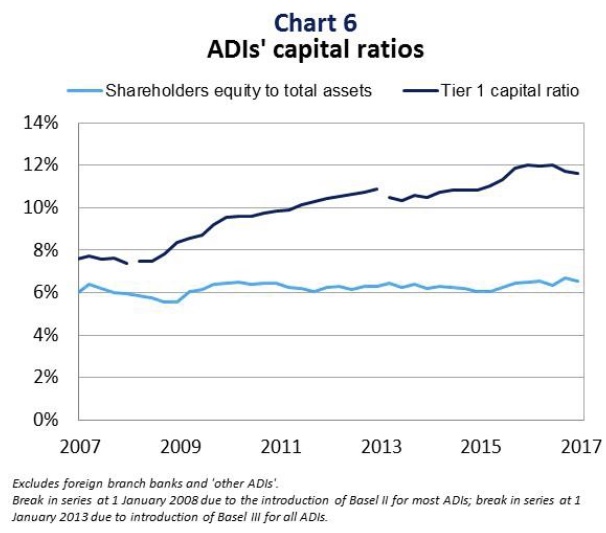

Each of these measures has been a tactical response to evolving conditions, designed to improve the resilience of bank balance sheets in the face of forces that might otherwise weaken them. We will monitor their effectiveness over time, and can do more or less as need be. We have also flagged that, at a more strategic level, we intend to review capital requirements for mortgage lending as part of our work on establishing ‘unquestionably strong’ capital standards, as recommended by the Financial System Inquiry (FSI).

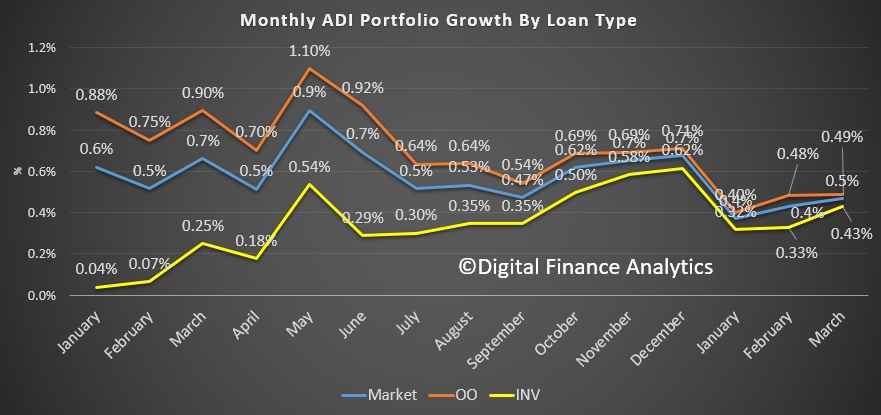

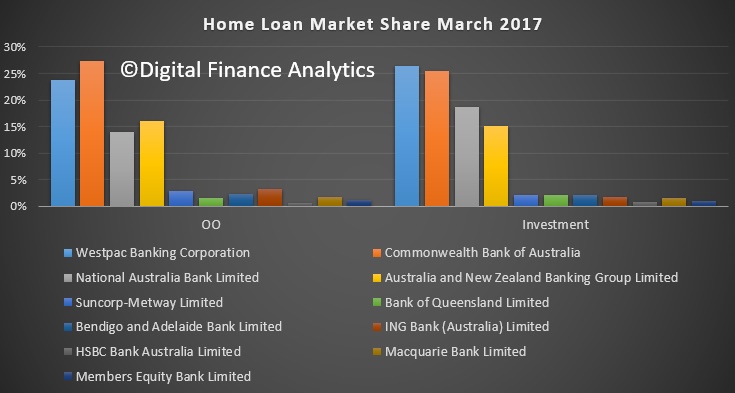

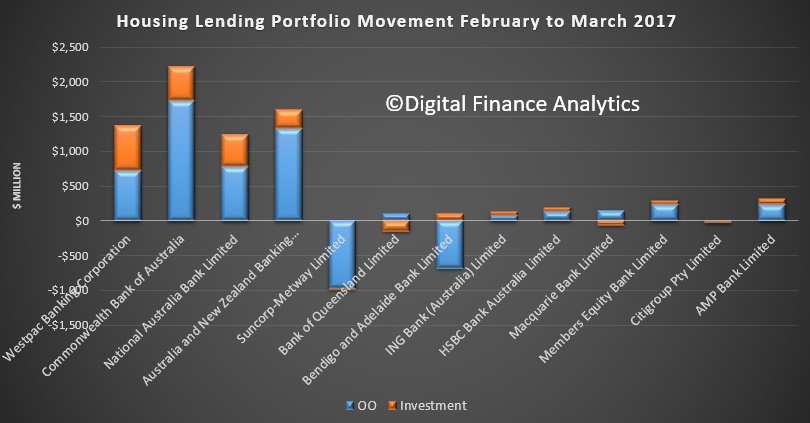

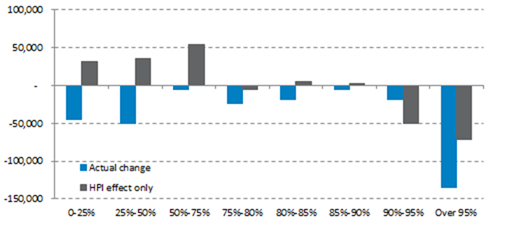

Looking at the impact so far, I have already noted that our earlier measures have helped slow the growth in investor lending (Chart 1), and lift the quality of new lending. Serviceability tests have strengthened, although as one would expect in a diverse market there are still a range of practices, ranging from the quite conservative to the less so. Lenders subject to APRA’s oversight have increasingly eschewed higher risk business (often by reducing maximum loan-to-valuation ratios (Chart 2)), or charged a higher price for it.

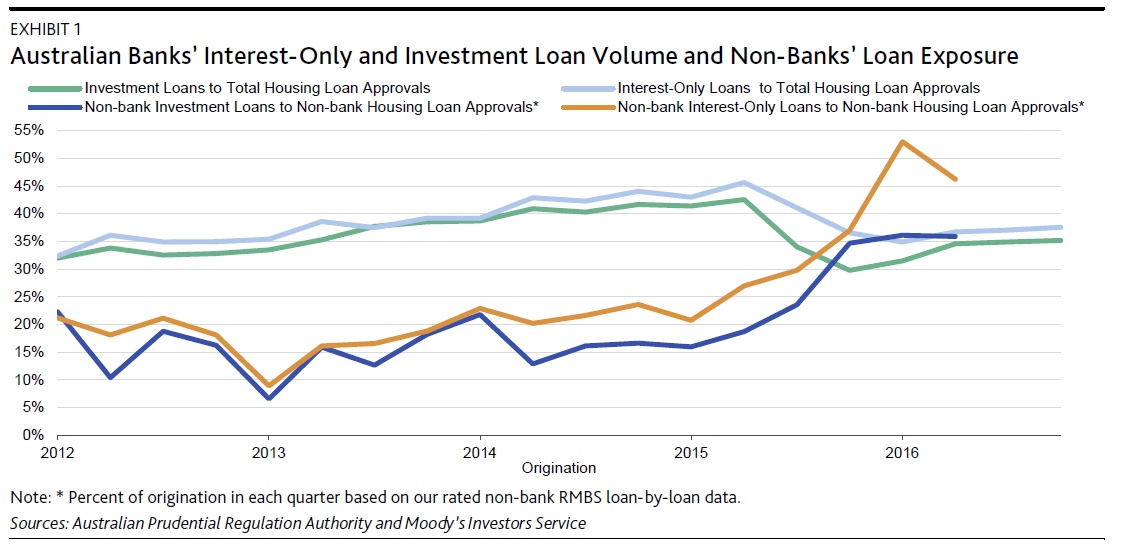

For example, there is now a clear price differential between lending to owner-occupiers on a principal and interest basis, and lending to investors on an interest-only basis (Chart 3). And as a result of our most recent guidance to lenders, we expect some further tightening to occur.

Looked at more broadly, the most important impact has been to reduce the competitive pressure to loosen lending standards as a means of chasing market share. We are not seeking to interfere in the ability of lenders to compete on price, service standards or other aspects of the customer experience. We do, however, want to reduce the unfortunate tendency of lenders, lulled by a long period of buoyant conditions, to compete away basic underwriting standards.

Of course, lenders not regulated by APRA will still provide competitive tension in that area and it is likely that some business, particularly in the higher risk categories, will flow to these providers. That is why we also cautioned lenders who provide warehouse facilities to make sure that the business they are funding through these facilities was not growing at a materially faster rate than the lender’s own housing loan portfolio, and that lending standards for loans held within warehouses was not of a materially lower quality than would be consistent with industry-wide sound practices. We don’t want the risks we are seeking to dampen coming onto bank balance sheets through the back door.

Commercial real estate lending

For all of the current focus on residential property lending, it has been cycles in commercial real estate (CRE) that have traditionally been the cause of stress in the banking system. So we are always quite interested in trends and standards in this area of lending. And tighter conditions for residential lending will also impact on lenders’ funding of residential construction portfolios – we need to be alert to the inter-relationships between the two.

Overall, lending for commercial real estate remains a material concentration of the Australian banking system. But while commercial lending exposures of APRA-regulated lenders continue to grow in absolute terms, they have declined relative to the banking system’s capital (partly reflecting the expansion in the system’s capital base). Exposures are now well down from pre-GFC levels as a proportion of capital, albeit much of the reduction was in the immediate post-crisis years and, more recently, the relative position has been fairly steady (Chart 4).

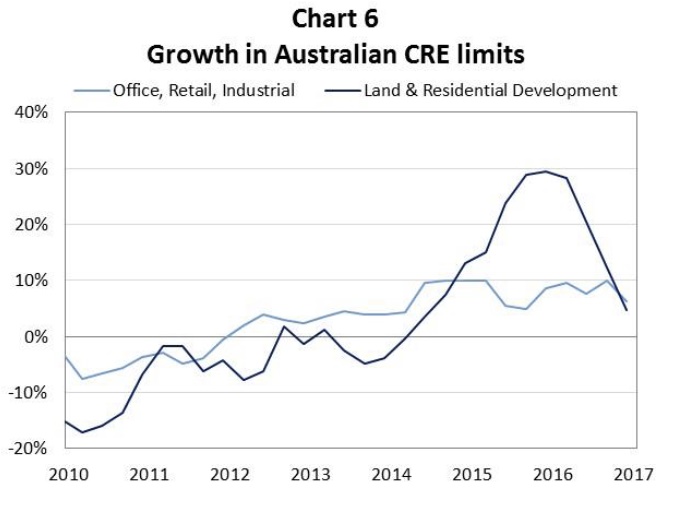

The story has been broadly similar in most sub-portfolios, with the notable exception of land and residential development exposures (Chart 5).

These have grown strongly as the banking industry has funded the significant new construction activity that has been occurring, particularly in the capital cities of Australia’s eastern seaboard. At the end of 2015, these exposures were growing extremely rapidly at just on 30 per cent per annum, but have since slowed significantly as newer projects are now being funded at little more than the rate at which existing projects roll off (Chart 6).

(As an aside, this is one reason why we opted not to reduce the 10 per cent investor lending benchmark for residential lending recently. There is a fairly large pipeline of residential construction to be absorbed over the course of 2017, and there is little to be gained from unduly constricting that at this point in time.)

In response to the generally low interest rate environment, coupled with relatively high price growth in some parts of the commercial market, low capitalisation rates and indications that underwriting standards were under competitive pressure, we undertook a thematic review of commercial property lending over 2016. We looked at the portfolio controls and underwriting standards of a number of larger domestic banks, as well as foreign bank branches which have been picking up market share and growing their commercial real estate lending well above system growth rates.

The review found that major lenders were well aware of the need to monitor commercial property lending closely, and the need to stay attuned to current and prospective market conditions. But the review also found clear evidence of an erosion of standards due to competitive pressures – for example, of lenders justifying a particular underwriting decision not on their own risk appetite and policies, but based on what they understood to be the criteria being applied by a competitor. We were also keen to see genuine scrutiny and challenge that aspirations of growth in commercial property lending were achievable, given the position in the credit cycle, without compromising the quality of lending. This was often being hampered by inadequate data, poor monitoring and incomplete portfolio controls. Lenders have been tasked to improve their capabilities in this regard.

Given the more heterogeneous nature of commercial property lending, it is more difficult to implement the sorts of benchmarks that we have applied to residential lending. But that should not be read to imply we have any less interest in the quality of commercial property lending. Our workplan certainly has further investigation of commercial property lending standards in 2017, and we will keep the need for additional guidance material under consideration.

Concluding remarks

So to sum up, property exposures – both residential and commercial – will remain a key area of focus for APRA for the foreseeable future. Sound lending standards are vital for the stability and safety of the Australian banking system, and given the high proportion of both residential mortgage and commercial property lending in loan portfolios, there will be no let up in the intensity of APRA’s scrutiny in the foreseeable future. But despite the fact the merit of our actions are often assessed based on their expected impact on prices, that is not our goal. Prudence (not prices) is our catch cry: our objective is to make ensure that, whatever the next stage of the property cycle may bring, the balance sheet of the banking system is resilient to it.