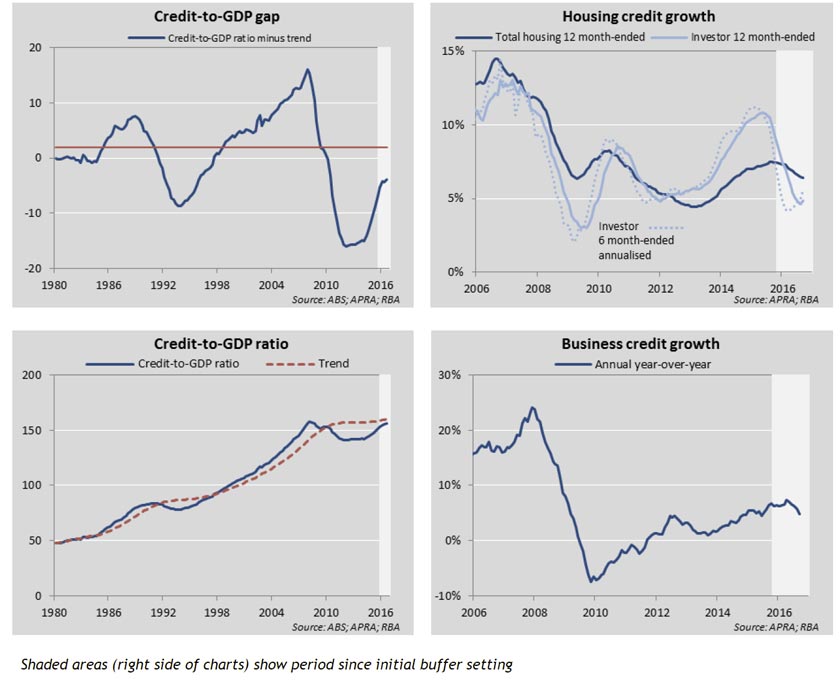

APRA has updated the mortgage lending guidance, to include more specific guidance on gifts for deposits, off-the-plan lending, allowance for vacant periods on rental proprieties, allowance for irregular income and confirmation of interest rate floor and buffers. There are also important comments relating to brokers, portfolio analysis and management responsibility. For example, banks will need to have ongoing awareness of households finances, rather than making a point-in-time, set-and-forget assessment. Whilst they say these changes are not material, in practice they are significant, and it suggests a more detailed “micro” analytical approach to lending scrutiny, rather than generic portfolio analytics. This is important and will impact. We think the costs of managing a mortgage portfolio just went up!

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has updated its expectations for sound residential mortgage lending practices for authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) following consultation with industry and other stakeholders.

APRA released for consultation a revised draft of Prudential Practice Guide APG 223 Residential Mortgage Lending in October 2016 to incorporate measures previously announced by APRA in 2014 or communicated to ADIs since that time.

The revisions to APG 223 are designed to ensure that the sound lending practices that have been implemented across the industry since late 2014 are maintained and reinforced.

As a result of the consultation, APRA has made a small number of refinements to the prudential practice guide, which are explained in a letter to ADIs released today. APRA does not expect these refinements to result in material changes to existing lending practices across the industry as a whole.

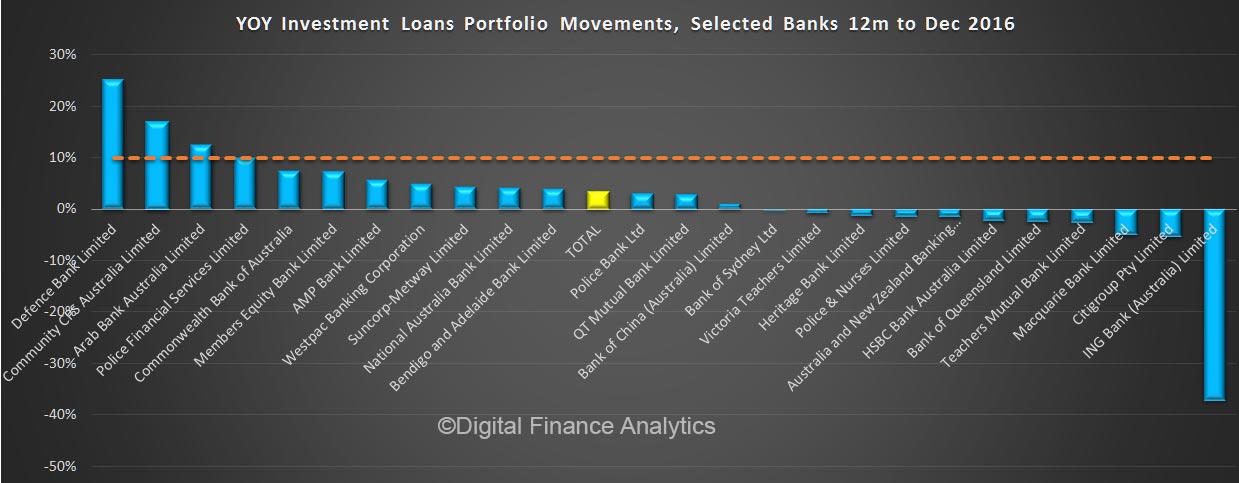

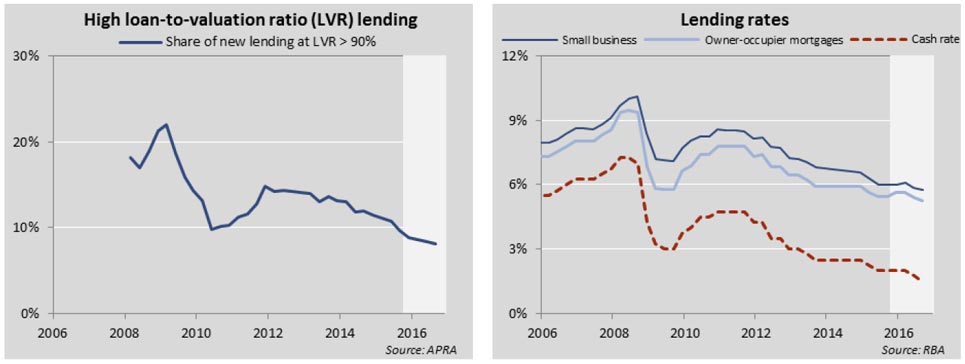

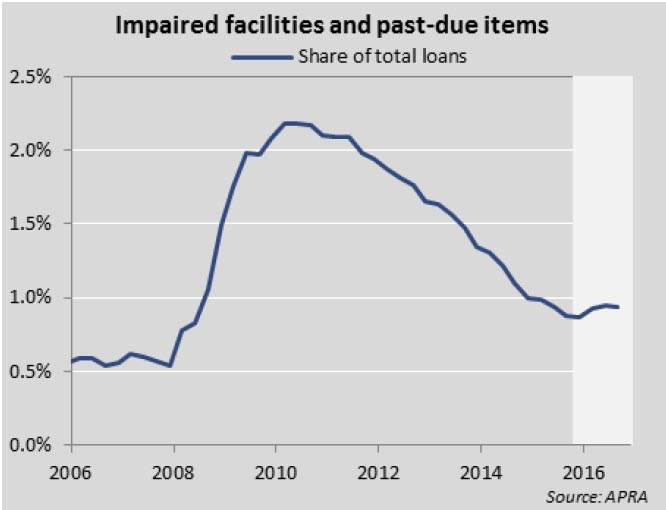

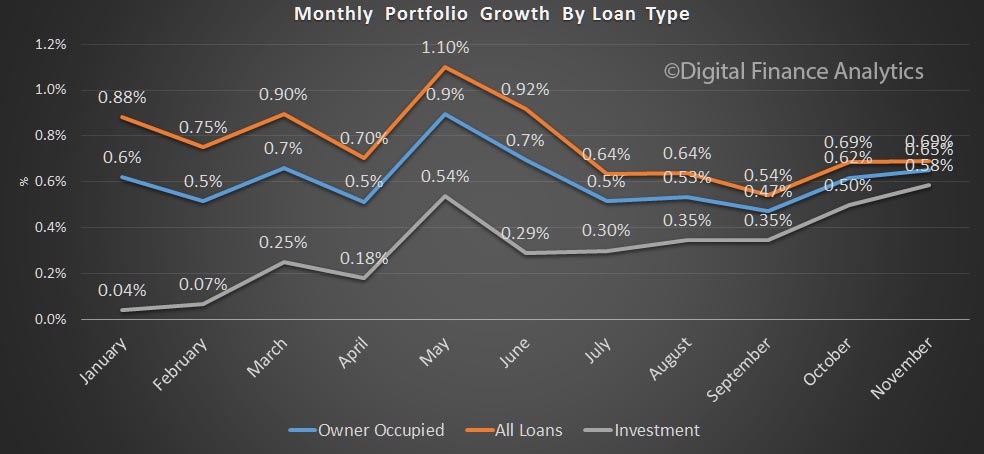

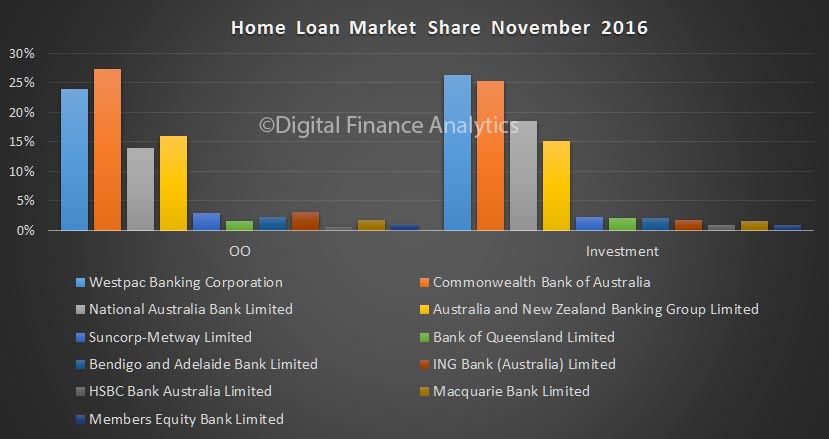

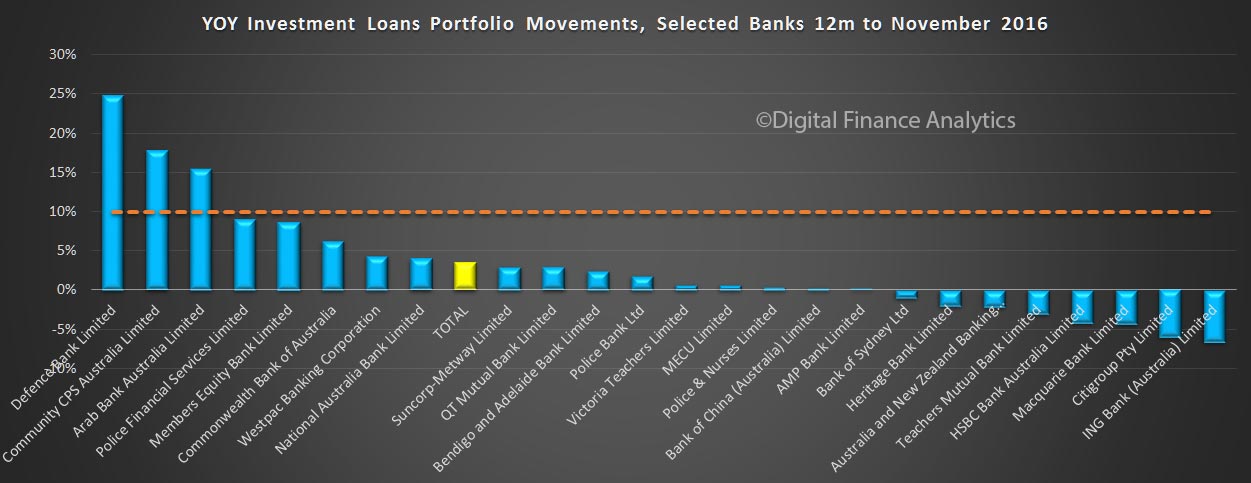

APRA is continuing to maintain its close monitoring and supervision of residential mortgage lending practices, including growth in investor lending, as part of its broader mandate to build resilience in the financial sector and promote financial system stability.

There are a few important comments which may trouble some lenders. For example:

Where residential mortgage lending forms a material proportion of an ADI’s lending portfolio and therefore represents a risk that may have a material impact on the ADI, the accepted level of credit risk would be expected to specifically address the risk in the residential mortgage portfolio.

In order to establish robust oversight, the Board and senior management would receive regular, concise and meaningful assessment of actual risks relative to the ADI’s risk appetite and of the operation and effectiveness of internal controls. The information would be provided in a timely manner to facilitate early corrective action.

A robust management information system would be able to provide good quality information on residential mortgage lending risks.

In Australia, it is standard market practice to pay brokers either an upfront commission or a trailing commission, or both. A prudent approach to the use of third parties for residential mortgage lending would include appropriate measures to ensure that commission-based compensation does not create adverse incentives.

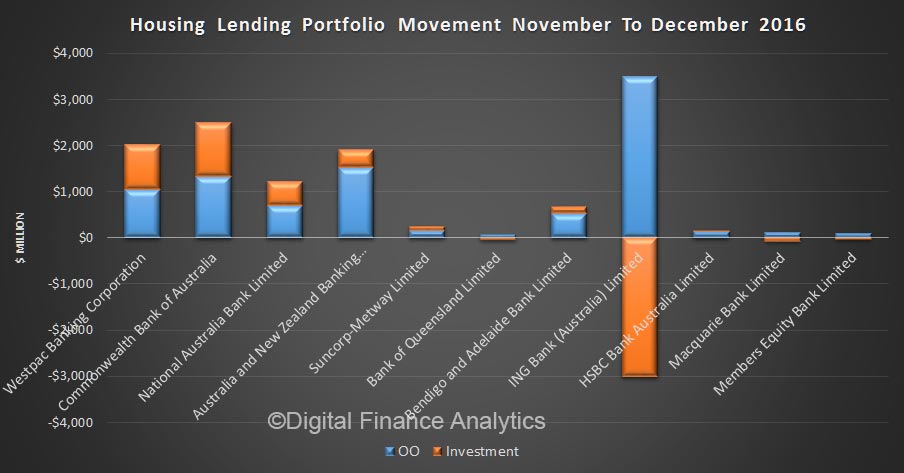

When an ADI is increasing its residential mortgage lending rapidly or at a rate materially faster than its competitors, either across the portfolio or in particular segments or geographical areas, a prudent Board would seek explanation as to why this is the case.

Where an ADI uses different serviceability criteria for different products or across different ‘brands’, APRA expects the ADI to be able to articulate and be aware of commercial and other reasons for these differences, and any implications for the ADI’s risk profile and risk appetite.

Good practice would apply a buffer over the loan’s interest rate to assess the serviceability of the borrower (interest rate buffer). This approach would seek to ensure that potential increases in interest rates do not adversely impact on a borrower’s capacity to repay a loan. The buffer would reflect the potential for interest rates to change over several years. APRA expects that ADI serviceability policies should incorporate an interest rate buffer of at least two percentage points. A prudent ADI would use a buffer comfortably above this level.

In addition, a prudent ADI would use the interest rate buffer in conjunction with an interest rate floor, to ensure that the interest rate buffer used is adequate when the ADI is operating in a low interest rate environment. Prudent serviceability policies should incorporate a minimum floor assessment interest rate of at least seven per cent. Again, a prudent ADI would implement a minimum floor rate comfortably above this level.

When assessing a borrower’s income, a prudent ADI would discount or disregard temporarily high or uncertain income. Similarly, it would apply appropriate adjustments when assessing seasonal or variable income sources. For example, significant discounts are generally applied to reported bonuses, overtime, rental income on investment properties, other types of investment income and variable commissions; in some cases, they may be applied to child support or other social security payments, pensions and superannuation income. Prudent practice is to apply discounts of at least 20 per cent on most types of non-salary income; in some cases, a higher discount would be appropriate. In some circumstances, an ADI may choose to use the lowest documented value of such income over the last several years, or apply a 20 per cent discount to the average amount received over a similar period.

In APRA’s view, prudent serviceability policies incorporate a minimum haircut of 20 per cent on expected rental income, with larger haircuts appropriate for properties where there is a higher risk of non-occupancy.

Good practice would be for an ADI to place no reliance on a borrower’s potential ability to access future tax benefits from operating a rental property at a loss. Where an ADI chooses to include such a tax benefit, it would be prudent to assess it at the current interest rate rather than one with a buffer applied.

Good practice would be for an ADI, rather than a third party, to perform income verification

Some ADIs use rules-based scorecards or quantitative models in the residential mortgage loan evaluation process. In such cases, good practice would include close oversight and governance of the credit scoring processes. Where decisions suggested by a scorecard are overridden, it is good practice to document the reasons for the override.

Interest-only loans may carry higher credit risk in some cases, and may not be appropriate for all borrowers. This should be reflected in the ADI’s risk management framework, including its risk appetite statement, and also in the ADI’s responsible lending compliance program. APRA expects that an ADI would only approve interest-only loans for owner-occupiers where there is a sound and documented economic basis for such an arrangement and not based on inability to service a loan on a principal and interest basis. APRA expects interest-only periods offered on residential mortgage loans to be of limited duration, particularly for owner-occupiers.

The nature of loans to SMSFs gives rise to unique operational, legal and reputational risks that differ from those of a traditional mortgage loan. Legal recourse in the event of default may differ from a standard mortgage, even with guarantees in place from other parties. Customer objectives and suitability may be more difficult to determine. In performing a serviceability assessment, ADIs would need to consider what regular income, subject to haircuts as discussed above, is available to service the loan and what expenses should be reflected in addition to the loan servicing. APRA expects that a prudent ADI would identify the additional risks relevant to this type of lending and implement loan application assessment processes and criteria that adequately reflect these risks.

Although mortgage lending risk cannot be fully mitigated through conservative LVRs, prudent LVR limits help to minimise the risk that the property serving as collateral will be insufficient to cover any repayment shortfall. Consequently, prudent LVR limits serve as an important element of portfolio risk management. APRA emphasises, however, that loan origination policies would not be expected to be solely reliant on LVR as a risk-mitigating mechanism.

ADIs typically require a borrower to provide an initial deposit primarily drawn from the borrower’s own funds. Imposing a minimum ‘genuine savings’ requirement as part of this initial deposit is considered an important means of reducing default risk. A prudent ADI would have limited appetite for taking into account non-genuine savings, such as gifts from a family member. In such cases, it would be prudent for an ADI to take all reasonable steps to determine whether non-genuine savings are to be repaid by the borrower and, if so, to incorporate these repayments in the serviceability assessment.

In the case of valuation of off-the-plan sales, developer prices might not represent a sustainable resale value. Consequently, in such circumstances, a prudent ADI would make appropriate reductions in the off-the-plan prices in determining LVRs or seek independent professional valuations.

A prudent ADI would regularly stress test its residential mortgage lending portfolio under a range of scenarios. Scenarios used for stress testing would include severe but plausible adverse conditions

LMI is not an alternative to loan origination due diligence. A prudent ADI would, notwithstanding the presence of LMI coverage, conduct its own due diligence, including comprehensive and independent assessment of a borrower’s capacity to repay, verification of minimum initial equity by borrowers, reasonable debt service coverage, and assessment of the value of the property.