The CBA today (yes on a Sunday!) has announced they are killing the ATM charge incurred by non-CBA customers withdrawing cash from their ATMs.

In a first for an Australian bank, Commonwealth Bank has removed ATM withdrawal fees so all CommBank and non-CommBank customers won’t be charged an ATM withdrawal fee by us when they take cash out at any of our 3,400 ATMs.

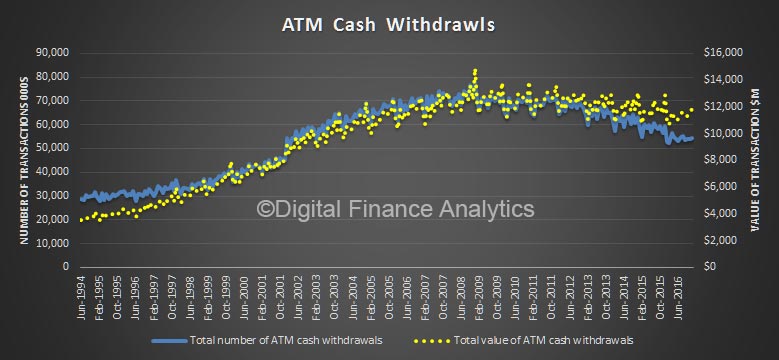

RBA data shows that Australians made more than 250 million ATM withdrawals from banks other than their own last year so the move is designed to increase convenience and bring savings.

“Australians have complained for some time about being charged fees for using another bank’s ATM,” Matt Comyn, Group Executive, Retail Banking Services, said today.

“We have been listening to consumer groups and our customers and understand that there’s a need to make changes that benefit all Australians, no matter who they bank with. This is one of the steps we’re taking to make that happen,” Mr Comyn said.

“As Australia’s largest bank, with one of the largest branch and ATM networks, we think this change will benefit many Australians and hopefully demonstrate our willingness to listen and act on customer feedback.”

No ATM withdrawal fee access applies to CommBank-branded ATMs and excludes Bankwest ATMs and customers using overseas cards.

The number of withdrawals from ATMs (and the number of ATMs in use) are falling, as other non-cash payment mechanisms proliferate – such as pay wave, debit cards and mobile payments. We expect the downward trajectory to accelerate as non-cash alternatives continue to grow. Customers can also get cash out at supermarkets, and this alternative has become popular for those who need to get their hands on real notes.

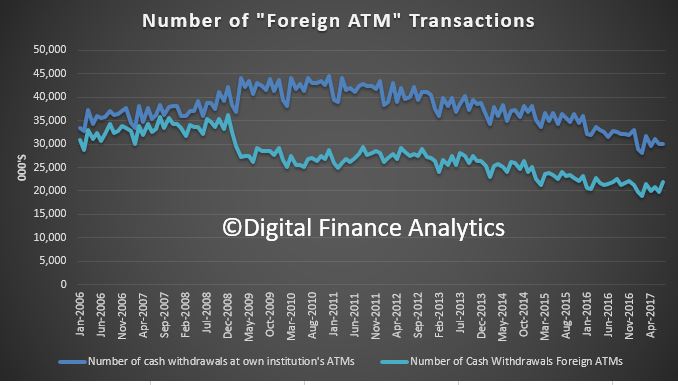

Under half have a charge attached, those are withdrawals from another bank’s ATMs.

As we said in a recent post there is a generation shift in play as digital natives continue to adopt smartphone based payment options, from Applepay, to NFC transactions in shops, or apps like paypal as well as the move to debt. Even digital migrants are using electronic mechanisms, such as smart phones, internet banking, contactless payments and Bpay is also a popular option.

Data from the RBA shows the volume of ATM cash withdrawal transactions has fallen by 15% over 3 years, whilst the gross value has slipped a little (and fallen in post-inflation adjusted terms). Debit card transactions are more than taking up the slack. But there is also more going on here.

We are approaching a tipping point where the economics of ATMs will not make sense, other than at a few high traffic locations, as there a fixed costs relating to installation and maintenance (including the cash top-up) and income is linked to volumes. There was a proliferation of third party ATMs in for example retail sites in the 1990’s, but these are getting less use too. So we think the number of machines will fall.

Meantime the ubiquitous smart phone is set to become your personal finance assistant, your electronic wallet and electronic credit card. Just do not lose your phone!

As a result, traditional channels such the the branch, ATM and even plastic are all under threat. Cash will become less important in every day life, but it will remain, used perhaps by people less comfortable with the technology, or in the black economy. It would not surprise me if down the track larger bank notes started to disappear under the guise of migration to digitally based more cost-efficient payment solutions, which just happen also to be easier to track.

Meantime, the ATM just got out-evolved by the smartphone.

Around $500 million was charged by banks to customers, and the average fee is $2 per transaction. CBA has the largest fleet of ATMs across the country, with more than 3,400.

This is a move which was expected, given there are overseas precedents to removing ATM fees, and volumes are falling. Of the 70,000 ATMs in the UK network, around 16,000 charge users a fee per withdrawal.

CBA will hope to gain a positive reaction, to counter the recent negative publicity surrounding its business. It will be interesting to see if other banks will follow (some will require IT modifications, so it may take some time), we suspect they might, which would be a small win for consumers.